Research and reporting by Kenny Bradley, Jeannie Carreiro, Colin Burdette, and Sarthak Tiwari

Imagine you notice a persistent, painful lump on your cervix. You consult your doctor, who asks your permission to conduct a diagnostic tissue biopsy. You have access to information about this procedure from your doctor, other medical professionals, and online forums. You agree to the biopsy, and the tissue is collected and sent to a pathologist for analysis. Your results are returned within the week, your doctor discusses them with you, and your care team formulates a treatment plan that prioritizes your physical health and well-being. Standard.

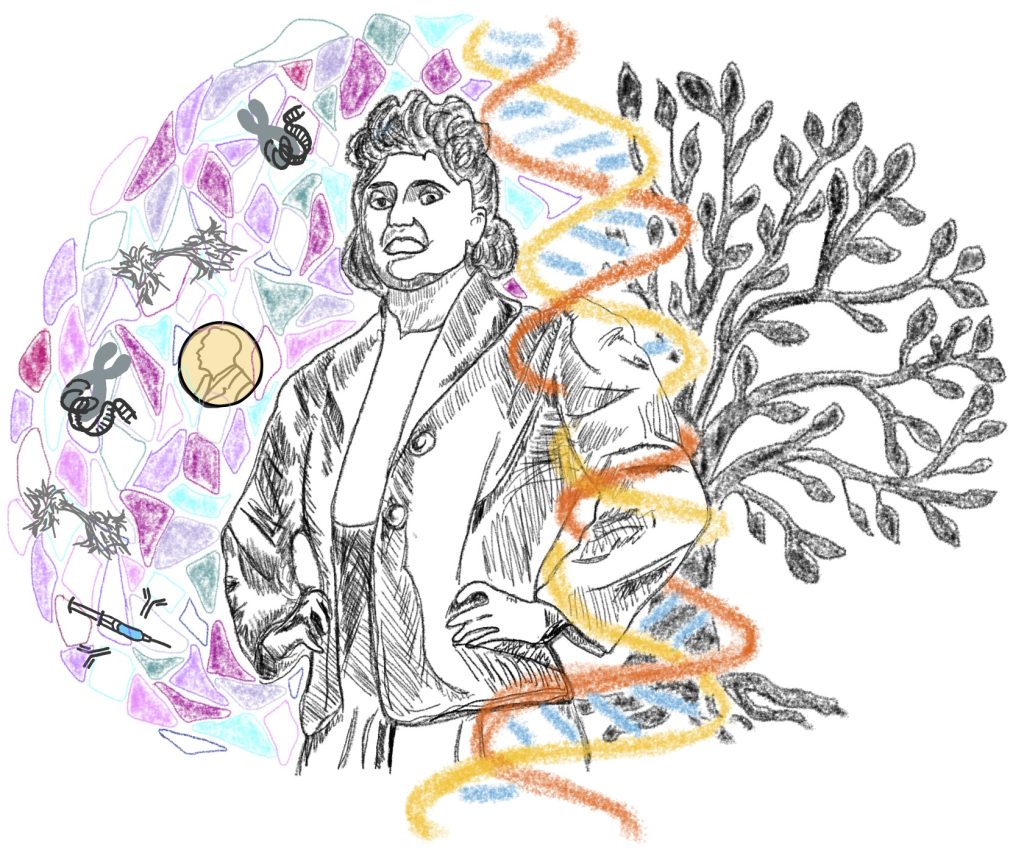

This is not what happened in 1951 to Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman with cervical cancer who was exploited by the physicians and scientists at Johns Hopkins Hospital responsible for her care. Henrietta’s biopsy forever changed modern biology without her even knowing it.

Henrietta Lacks was born in Virginia in 1920, where she was raised by her grandparents and worked as a tobacco farmer from an early age. In her early adulthood, she married her cousin David “Day” Lacks and soon after moved to Baltimore to raise their five children: Deborah “Dale” Lacks, Lucile “Elsie” Lacks, Zakariyya Bari Abdul Rahman (born Joseph Lacks), David Lacks Jr., and Lawrence Lacks. During and after Henrietta’s fifth pregnancy with Joseph, her health problems began to arise—excessive vaginal bleeding, feeling a “knot” inside of her, and a lump on her cervix. She began to seek treatment, without her family knowing, at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Henrietta Lacks’s tumor cells were obtained without consent during a treatment for her cancer. Dr. George Gey and his assistant Mary Kubicek isolated cells from Henrietta’s sample and discovered that, unlike any other cells they’d tried to culture, Henrietta’s never ceased dividing. Her cell line, referred to only as “HeLa,” was immortal, and had enormous potential to transform scientific research. HeLa cells were a dream come true for biologists studying cell biology and cancer, and they revolutionized tissue culture practices in the U.S. and abroad, including in labs here in the Tri-I. Research using HeLa cells has resulted in three Nobel Prize awards in Physiology and Medicine, and over 100,000 publications to date. Following the inception of the HeLa cell line, medical professionals and scientists were quick to forget the woman from whom HeLa cells were unethically derived. The Lacks family was left completely uninformed and excluded as Henrietta’s DNA was exploited for academic and financial profit.

The Journey to Immortality and Growth of the HeLa Machine

The Early 1900s

In 1912, Rockefeller Institute scientist Alexis Carrel shocked the scientific community by claiming to have developed a tissue culture technique to keep cells alive indefinitely. The chicken heart tissue he began culturing that year continued to proliferate until 1946, according to Carrel’s published papers—defying all prior knowledge about the lifespan of cells. His Nobel Prize-winning work was touted as groundbreaking until the 1960s, when it was revealed that other scientists were unable to replicate his experiments., In the wake of this scandal, scientists relaunched efforts in the late twentieth century towards achieving and maintaining cellular immortality.

Carrel’s research was rooted in the culturally pervasive belief in eugenics. He saw his work as something to benefit only the healthiest members of society and believed in the euthanization of people with certain racial/ethnic backgrounds, mental and physical abilities, and criminal histories. This deep-rooted tradition of eugenics in science and medicine, which both pre-dated and was promoted by Carrel, shaped the way in which scientists continued to view Henrietta Lacks as a research subject and subsequently decided who benefitted from the use of HeLa cells. The lack of consideration and respect for Henrietta and the Lacks family’s humanity was a reflection of the cultural norms and opinions of the time.

The Collection

Race relations in the United States at the time of Henrietta Lacks’s medical treatment provide insight into the less-than-ideal experience she had at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Maryland, like the other Southern states in the U.S., enforced Jim Crow laws until they were overturned in 1965. Black individuals were prohibited from attending the same schools, going to the same hospitals, or using the same restrooms as their White counterparts. State and national laws legitimized the use of brute police force to punish perceived infractions. Jim Crow policies blocked access to equitable healthcare for Black people like Henrietta in the Baltimore area and beyond. Her only option for receiving any healthcare was at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, which was established in 1889 to “provide care to anyone, regardless of sex, age or race.”

Despite this pledge to provide equitable care, deeply ingrained cultural beliefs that Black people were inferior resulted in medical care that was apathetic, cold, and often cruel. A common belief by scientists who worked in public wards at this time was that “it was fair to use them [African-Americans] as research subjects as a form of payment.”, This mentality was consciously or subconsciously brought to Henrietta’s examination room that day in 1951, when the doctors neglected to ask for Henrietta’s consent to remove tissue from her body, which they stored in the lab’s “Colored” freezer.

It was only during Henrietta’s autopsy in October of 1951 that the scientists who had been working with her cells acknowledged her humanity. “It hit me for the first time that those cells we’d been working with all this time and sending all over the world, they came from a live woman,” Mary Kubicek later said. “I’d never thought of it that way.”

The Early Use

At the height of the polio epidemic in 1952, scientists needed a vessel to grow large amounts of poliovirus for research purposes. Cue HeLa cells, whose susceptibility to poliovirus and ability to grow at rapid rates made them the perfect tool to test vaccines. The idea of a “HeLa factory” became a reality, being established at the Tuskegee Institute in the early ‘50s as an opportunity to provide jobs to Black individuals. These jobs and this research benefited predominantly White people suffering from polio. This polio research using a Black woman’s cells was occurring at the same time as and within the same institute that was conducting one of the most notably unethical and dangerous experiments in the United States, The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment.

In the years following the polio research, the usage of HeLa cells expanded. One of the first experiments done to understand the impact of X-rays on human cells was conducted using HeLa cells in 1956. The same year, HeLa cells were used to establish a method for characterizing cell growth that is used to diagnose cancerous cells to this day. The cells were also the perfect model to investigate the benefits of drugs that treat blood cancers or sickle cell anemia. Henrietta’s cells even traveled to space in the same year, 1964, where NASA scientists used them to study the effect of radiation and space travel on human cells.

In the 1950s, Dr. Chester Southam, an immunologist and oncologist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering and Weill Cornell, used HeLa cells for a particularly egregious set of experiments that would certainly be illegal by today’s standards. Southam was interested in injecting live HeLa cells into individuals to understand how tumors proliferate. He began by injecting millions of HeLa cells into patients with leukemia who came into his office, under the guise of testing their immune systems. These patients were completely uninformed about the injection of malignant cells into their bodies, and therefore obviously unable to consent. Within a week, the patients developed aggressive tumors like the ones that plagued Henrietta. Southam then moved to another frequently exploited group: prisoners. In total, Southam injected HeLa cells into over 600 people. Later scrutiny of his problematic medical activities revealed that his work was comparable to the medical war crimes conducted during the Holocaust and prosecuted in the Nuremberg trials. Southam was found guilty of fraud and unprofessional conduct. His punishment? Probation for a year.

The Mortal Family Living Alongside the Immortal Cells

Where was Henrietta’s family during all of this? What did they know about the scientific legacy Henrietta had left after her death? While transformative research was being conducted using the HeLa cell line, her family had no idea that their mother’s cells had been kept, nor did they have the scientific knowledge to understand the prospect of cell culture and how cells could be used for medical advancements.

Henrietta’s children lived in poverty, suffered at the hands of abusive caretakers,and experienced food insecurity and incarceration. Like many Black Americans, the Lacks family was effectively ignored by legal and social systems in the United States. This truth feels paradoxical because the cells that were being used to revolutionize so many aspects of science held the same DNA as the individuals whose lives were generally deemed as unimportant, unless for monetary gain.

It wasn’t until 1973 that Henrietta’s daughter-in-law became aware that Johns Hopkins had the cells. Naturally, the family began contacting Hopkins for more information. In response, Hopkins doctors misled the family into agreeing to donate blood by telling them it was to test for cancer. In actuality, the HeLa cell line had been discovered to be contaminating many other cell lines in laboratories across the globe, and scientists wanted more nearly related samples so they could better identify the original cells. Following the collection of multiple family members’ blood samples, Hopkins ghosted the family—no contact, no explanation, no follow-up.

What followed was years of miscommunication, misinformation, and the continued erosion of trust in the scientific and healthcare systems. The family was unaware that since the 1960s, the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) had sold HeLa cells for almost $300 per vial, or that other companies like Invitrogen were making significant amounts of money off of the cells extracted from Henrietta. The family became aware early on that research intended to help people was being done in the HeLa cell line, but once they realized how profitable the cells had become—there are over 11,000 patents associated with the line—they began to pursue financial compensation.

As the Lacks family’s awareness about the use and commercialization of the HeLa cell line developed, the kinds of research being done in the cells continued to expand. Many labs in the Tri-I continue to use the line, citing the ease of use, wide variety of usage, and low cost as primary reasons for their decision to use the cells in their research. for example, work utilizing HeLa cells built the foundation of Titia de Lange’s research program in the early 2000s. The lab continues to use the cells today. Many other labs in the Tri-I also work with HeLa cells, citing ease of use, wide variety of usage, and low cost as primary reasons for this decision.

Although the scientific community had grown familiar and comfortable with the cells of Henrietta Lacks, her family had never even seen them. In the early 2000s, the Lacks family finally received an invitation to see the cells that changed the world, the cells of their beloved Henrietta. Christoph Lengauer at Hopkins explained to Henrietta’s adult children how HeLa cells were kept alive and used in experiments, and allowed them to see the cells from their mother with their own eyes. Lengauer explained to the family how the cells still held Henrietta’s genetic material, even after all of this time. He also advised the family to pursue compensation for the use of their mother’s cells. Until this point, the Lacks family had been completely excluded from all conversation and decision-making about their mother’s cells. This lawsuit would become the family’s first opportunity to redress the historic wrongdoing against Henrietta Lacks.

The Lawsuit

Following the publication of Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks in 2010, there was revitalized interest in this story of unethical treatment and the commercialization of biological materials. Henrietta’s family raised concerns that their genetic material was publicly available, as HeLa genomes had been made accessible through years of research without their consent. In 2013, the family came to agreements with the NIH that restricted access to HeLa cell genomes. “It was shocking and a little disappointing, knowing that Henrietta’s information was out there… It was like her medical records are just there to view with the click of a button,” said one of her relatives. “They didn’t come to the family… It was like history was repeating itself.” The agreement states that any future genomes produced of HeLa cells cannot be published unless the family allows it, a big win in terms of being included in scientific conversation as members of the general public.

In terms of financial compensation, the family decided to pursue legal action when lawyers and scholars noted the “discrepancy in status and financial stability” that the descendants of Henrietta Lacks have experienced, contrasted with the massive compensation packages received by biotech companies profiting off the cell line. With the assistance of Ben Crump, a civil rights attorney mainly focusing on cases surrounding racial injustices, the family sued Thermo Fisher and received a $9.9 million settlement. Though a large amount of money, $9.9 million is but a fraction of the over $26 million the CEO of Thermo Fisher received in 2023. Do these corporations pay because they understand the wrongdoing, or to hush any complaints?

How Do We Remedy This Story as Scientists?

Henrietta Lacks is most often honored through symposia and awards that bear her name, but does this absolve us of what happened to her? When research institutions do acknowledge her story, it’s often watered down and confined to a page, or even a single paragraph. What can we do as scientists who are at the bench, carrying out the work described in this article? How do we prioritize humanity in our research? How can we continue to honor Henrietta Lacks? Here are some actionable ideas:

- Continue to conduct ethical research

- Remember that people are people—just because an experiment is blinded doesn’t mean a subject’s right to respect does not exist

- Engage in unclouded discussion of the honest history that takes into account the goals of the science at the time

- Acknowledge the problematic state of scientific research at the time, mostly driven by the problematic nature of society at the time—this increases awareness of contexts that people may not be aware of. This also allows people to view what they thought they knew in a new light.

It is unlikely that the large-scale, corporation-driven use of HeLa cells will be eradicated in our lifetimes, due to the cost of research and the established science that has come from them. But on the individual level, you can ask yourself some questions:

- Am I educated on the origins of the tools I am using in the lab?

- Is the research I am involved in aimed at benefiting humanity through knowledge or care?

- Is the research I am doing or contributing to something that could exclude or other people?

Often, we bench scientists can hyperfixate on the nitty-gritty details of our experiments, lacking awareness of the context in which our work has even been made possible. When we forget to look outward, or we choose to remain ignorant of the ways that science has failed others, we remain stunted. From this stuntedness, we run the risk of allowing a story like Henrietta Lacks’s to be repeated—a story in which science forgot about humanity.

References

1. Alexis Carrel’s Immortal Chick Heart Tissue Cultures (1912-1946) | Embryo Project Ency- clopedia. (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2024, from https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/alex- is-carrels-immortal-chick-heart-tissue-cul- tures-1912-1946

2. Baptiste, D., Caviness‐Ashe, N., Josiah, N., Commodore‐Mensah, Y., Arscott, J., Wilson, P. R., & Starks, S. (2022). Henrietta Lacks and America’s dark history of research in- volving African Americans. Nursing Open, 9(5), 2236–2238. https://doi.org/10.1002/ nop2.1257

3. History of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2024, from https:// www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/history/ history-of-jhh

4. Hornblum, A. M. (2013, December 28). NYC’s forgotten cancer scandal. https://nypost. com/2013/12/28/nycs-forgotten-can- cer-scandal/Jim Crow and Segregation | Classroom Ma- terials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress. (n.d.). [Web page]. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Re- trieved January 31, 2024, from https://www. loc.gov/classroom-materials/jim-crow-seg- regation/

5. Mulford, R. D. (1967). Experimentation on Human Beings. Stanford Law Review, 20(1), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.2307/1227417 Puck, T. T., & Marcus, P. I. (1956). Action of x-rays on mammalian cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 103(5), 653–666. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.103.5.653

6. Puck, T. T., Marcus, P. I., & Cieciura, S. J. (1956). Clonal growth of mammalian cells in vitro; growth characteristics of colonies from single HeLa cells with and without a feeder layer. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 103(2), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1084/ jem.103.2.273

7. Ritter, M. (2013, August 7). Feds, family reach deal on use of DNA information. AP News. https://apnews.com/general-news-aebb- 5c9db32a4e208925a0f0e47917cb

8. Skene, L., & Brumfield, S. (2023, August 1). Family of Henrietta Lacks settles law- suit against Thermo Fisher Scientific | AP News. https://apnews.com/article/henri- etta-lacks-hela-cells-thermo-fisher-scientif- ic-bfba4a6c10396efa34c9b79a544f0729 Skloot, R. (2010). The Immortal Life of Henri- etta Lacks. Broadway Paperbacks.

9. Thaldar, D. W. (2023). Who would own the HeLa cell line if the Henrietta Lacks case hap- pened in present-day South Africa? Journal of Law and the Biosciences, 10(1), lsad011. https://doi.org/10.1093/jlb/lsad011 Tuskegee Study – Timeline – CDC – OS. (2023, October 3). https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/ timeline.htm

10. Vernon, G. (2019). Alexis Carrel: ‘father of transplant surgery’ and supporter of eugen- ics. The British Journal of General Practice, 69(684), 352. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjg- p19X704441

11. Young, C. W., & Hodas, S. (1964). HYDROXY- UREA: INHIBITORY EFFECT ON DNA METAB- OLISM. Science (New York, N.Y.), 146(3648), 1172–1174. https://doi.org/10.1126/sci- ence.146.3648.1172

12. Zhukov-Verezhnikov, N. N. (1964). Results of microbiological and cytological inves- tigations on vostok type spacecraft (itogi mikrobiologicheskikh i tsitolo- gicheskikh issledovaniy na kosmicheskikh korablyakh tipa ’ “vostok”’). http://archive.org/details/ nasa_techdoc_19650002618