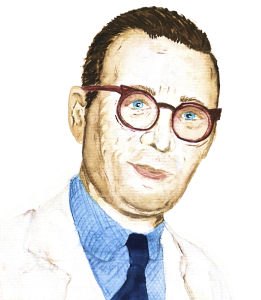

Earlier this month, the Rockefeller University awarded Italian physicist Dr. Carlo Rovelli the Lewis Thomas Prize for his exceptional writing about science and philosophy. Dr. Rovelli has authored seven internationally acclaimed books, including There are Places in the World Where Rules Are Less Important Than Kindness (2020) for which he is being honored. The Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science celebrates physicians and scientists who have simultaneously contributed great knowledge to their respective field and to the general public through accessible, inspirational authorship. Past recipients include social psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt (2022), oceanographer Sylvia Earle (2017), and surgeon Atul Gawande (2014) to name a few. Thirty-one years ago, in 1993, this prize was established in honor of Dr. Lewis Thomas shortly after he passed away at the age of eighty. Why is one of the two annual Rockefeller University awards granted in honor of him? Who was Dr. Lewis Thomas?

Shaping the Science of Medicine in NYC

Born in Flushing, Queens, Dr. Lewis Thomas was a renowned immunopathologist, educator, and academic administrator. He previously held research appointments in the medical schools of Johns Hopkins University, Tulane University, and the University of Minnesota before serving as the dean of both, New York University School of Medicine and subsequently Yale School of Medicine. Thomas played a significant role in shaping the science of medicine at each of these institutions. He was an ardent advocate for greater funding in medical research, particularly at the frontiers of biological understanding. In 1972, Thomas helped to raise the resources to recruit Rockefeller University scientist George Palade and his wife Marilyn Farquhar to start a new program at Yale integrating cell biology into medical education. The research environment that Thomas curated supported the research for which Palade would go on to win the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his pioneering work in cell biology.

Thomas’ legacy of leadership lives on through the Tri-I community, as he played an instrumental role in forging a collaboration between Rockefeller University, Cornell University, and MSK that we all know as the Tri-I Program. He served as President of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between 1973 and 1980, Chancellor between 1980 and 1983, and President Emeritus until his death. He was also a Rockefeller University Adjunct Professor and Visiting Physician. There is a letter in the NIH National Library of Medicine archives sent by Thomas to Nobel laureate Dr. Joshua Lederberg of Stanford University in early August of 1978 that details how exactly a Rockefeller-MSK clinical research partnership would enhance the recruitment and education of M.D.-Ph.D trainees. He proposed linking the two hospitals in the same way that MSK was linked to Cornell. Thomas wrote, “I believe that we have an opportunity here to create a setting which will attract the brightest of the country’s young talents for the study of human disease mechanisms, including cancer”. Thomas’ association with Rockefeller University actually goes back to 1942, when he spent five years conducting research on infectious disease with the then-Rockefeller Institute and a United States Naval Medical Research team, including in the lab of pioneering virologist Dr. Tom Rivers. In a 1989 interview with the Rockefeller newspaper News and Notes, Thomas credits his training at Rockefeller as the catalyst for “his obsession with virology and immunology”.

In the same interview, Thomas reflects on the difficulties of the growing scientific enterprise of biomedical research in acquiring funding. “My main worry is that some of the fun is going out of biomedical science,” he states before adding, “I’d like to see a great deal more money put into biomedical research”. Thomas saw a great need to change the narrative around health, medicine and biology in both academia and the public. In retrospect, it is entirely understandable how Lewis Thomas turned to “writing science for a general audience… more or less by accident,” as he explains, because the “hideous prose used in writing up whatever I was doing in the laboratory” lacked the personal sense of conversation needed to showcase the impact of the biological mysteries being revealed. He recognized that ‘modern’ miracles in medicine typically resulted from years, if not decades, of basic research. Thomas was driven to ensure the early investment of adequate resources into basic research in order for impactful change in the future. During his tenure at MSK, Thomas published six collections of essays and solidified his legacy as one of the best science writers of the 20th century. In his autobiography, The Youngest Science: Notes of a Medicine-Watcher (1984), Thomas reflects on the evolution of medicine, his experience as a physician-scientist, and the promise of medicine as an enterprise in the 21st century. A promise, he felt, that was dependent on strengthening the funding, academic systems, and public support for biomedical research.

The Scientist as a Poet: Notes of a Biology Watcher

The history of medicine, including the evolution of medical education, was of as much interest to Thomas as the philosophy of the human experience. The more research revealed the mechanisms underlying life, the more questions arose about what life means. He found lessons from nature—parallels about life, death, happiness, order, chaos, and community in cells. He also found lessons from art and culture—parallels to the innumerable sense of scale of biochemical molecules, organelles, and cells that make up our own bodies. He was a prolific writer on these topics and more, sharing insights gained over decades of study and reflection.

From his undergrad days at Princeton University writing poems and parodies for the university newspaper to selling poetry to The Atlantic, then called The Atlantic Monthly Magazine, during his medical training at Harvard Medical School, Thomas refined his witty and unconventional philosophical voice. He initially viewed his science-adjacent musings as entirely separate to the discourse of peer-reviewed papers and conference talks. Later on, he started to carry the spirit of poetry into his medical lectures, which ultimately led to his popular bimonthly column, ‘Notes of a Biology Watcher’, in the New England Journal of Medicine. He built a bridge between the siloed worlds of humanities and science that would guide hundreds of thousands of readers in addition to scientific and medical trainees.

Thomas’ first published collection titled The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher (1974) earned him two U.S. National Book Awards. Thomas brings the reader on a journey across scales of biology, starting with what makes us human biologically before looking at what makes societies like an organism and what makes the Earth like a living cell. He shares his fond thoughts on mitochondria in “Organelles as Organisms”; “They feel like strangers, but the thought comes that the same creatures, precisely the same, are out there in the cells of seagulls, and whales, … I cannot help thinking that if only I knew more about them, and how they maintain our synchrony, I would have a new way to explain music to myself” (The Lives of a Cell). Thomas found an overlapping beauty in organismal biology and classical music, as both are an emergent collective of many individual parts.

His second collection of essays titled The Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher (1979) continues to explore the paradoxical mechanisms nature has devised to mark self versus not-self, including symbiosis and various antagonistic relationships ranging from viral infection to cancers all the way to the Cold War. He viewed pathogenic bacteria and viruses as the outliers, in contrast to the innumerable beneficial microbes and viral carriers of genetic information. Thomas’ third collection, Late Night Thoughts on Listening to Mahler’s Ninth Symphony (1983), ventures deeper into his feelings on the notion of death, from ‘natural causes’ to the modern plague of possible nuclear annihilation.

On the process of science research itself, Thomas notes that “it sometimes looks like a lonely activity, but it is as much the opposite of lonely as human behavior can be” (The Lives of a Cell). He goes on, “There is nothing so social, so communal, and so interdependent. An active field of science is like an immense intellectual anthill; the individual almost vanishes into the mass of minds tumbling over each other, carrying information from place to place, passing it around at the speed of light” (The Lives of a Cell). Academia is not perfect, but it is an evolving community of people united under a singular drive to advance our understanding of life. Thomas often referred to medicine as the youngest science with innumerable opportunities to grow.

In his final publication, he makes a pointed observation: “much of what is happening in both cancer and brain research is the outcome of basic research” (The Fragile Species, 1992). To highlight just how important continued basic research will be, Thomas ultimately concludes that “this is a very big place, and I do not know how it works. I am a member of a fragile species, still new to the earth, the youngest creatures of any scale, here only a few moments as evolutionary time is measured, a juvenile species, a child of a species.”

So who was Dr. Lewis Thomas? He was a brilliant physician-scientist who merged a sense of wonder for nature with a deeply grounded sense of humanity, putting science in a new light for countless people.