George Cross

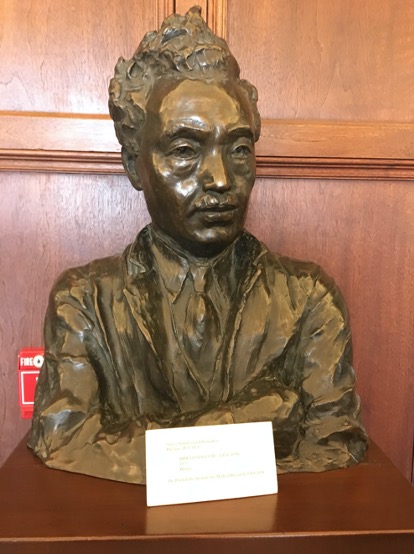

Who among you could guess what experience my grandfather, great uncle, and the revered Rockefeller scientist Hideyo Noguchi (whose bust decorates our library) have in common, and how might they have met?

Friends and colleagues who are nice enough—or foolish enough—to enquire about my activities in retirement risk being regaled about two undertakings that have preoccupied me in the past few years: political activism and genealogical research. With the coronavirus shutdown and the bleak weather upstate this spring, I no longer had an excuse to evade writing about either. After five years of research, for myself and others, I have a few ancestry stories I’d like to tell. One of them concerns the unlikely connection between my grandfather, my great uncle, and Hideyo Noguchi, the revered Japanese bacteriologist sometimes (mistakenly) credited with discovering the causative agent of syphilis. In December 1900, Noguchi travelled to the United States to join Simon Flexner’s lab in Philadelphia and moved with Flexner to The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in 1904, where he worked on syphilis and other infectious diseases, including, fatefully, yellow fever.

After our parents died, my cousin Peter and I discovered a few boxes containing family documents we had not previously seen. To our amazement, these boxes contained some of our grandfather’s ships’ logs, notebooks, letters, and other original documents. Having the time and knowing almost nothing about our ancestors, even those in our grandparents’ generation, Peter’s wife Sheila and I started our projects. Grandfather William Herbert Cross (1870–1918) was a Master Mariner, certified to captain merchant ships. He, along with his older brother Charles and younger brother Frederick, moved up the ranks to this position in the 1890s. They captained mainly cargo ships, both sail- and steam-powered, circumnavigating the globe and making many crossings of the Pacific Ocean between Japan and the United States. I have notes and photographs showing that my grandfather carried a few famous passengers to Alaskan gold-rush towns, and I have photographs of him taken in Brooklyn, when he was an apprentice seaman.

Today’s tale starts with one letter we inherited, which was remarkable for the insight it provided into Herbert’s character and his close relationship with Charles. This letter to Charles, dated 1909, announced in flowery language his plan to marry. The letter included the following passage, with a riff on the number nine: “…the date fixed for this voyage is Sep 29th, 1909. My intended wife is 29 and I am 39 so you will see we are not seven but 9, not No. 9 Yokohama, no I have given that a miss for a long time.”

Which brings us to the answer to my first question, initially provided—unsurprisingly—by Google. No. 9 Yokohama is a brothel; a quite famous one apparently, or perhaps I should say infamous. Some of its history recorded online includes a photograph showing “Gorgeously dressed prostitutes…standing in the windows of the Nectarine brothel in Yokohama, a world-famous house of prostitution also known as No. 9 or Jimpuro [sometimes translated as Jinpuro or Shinpuro].” This website went on to describe No. 9 as well as one of its more famous patrons:

Jimpuro was not only popular with foreigners, but with Japanese men as well. In 1900, bacteriologist Hideyo Noguchi (1876-1928), who now graces Japan’s 1,000-yen bill and was nominated for a Nobel Prize three times, blew almost 500 yen (a small fortune at the time) at Jimpuro during a single night of pleasure. Some 300 yen of which he had received from an acquaintance, on condition that he marry her niece. Even worse, part of the money was supposed to have been used for the purchase of a ticket for passage to America. He managed [again] to borrow money from a friend and did make it to the States, where he eventually became a top bacteriologist at the Rockefeller Institute. He never married the niece, though, and left the repayment of the 300 yen to the same friend he borrowed money from for the ticket to the USA.

To publish this story, I thought I’d better do some fact checking. I found the above account to be entirely consistent with the 1929 Science obituary written by Rockefeller’s first president, Simon Flexner, and with the extensive and authoritative 2003 biography Dr. Noguchi’s Journey: A Life of Medical Search and Discovery written by Atsushi Kita and translated into English by Peter Durfee. The story of how Noguchi overcame physical disability and an impoverished rural background to find his way to Rockefeller is truly awesome. I recommend Kita’s book, which is in the Rockefeller library, to anyone interested in the early twentieth century history of viral and bacterial diseases; it’s a very readable and fascinating history of a Japanese and Rockefeller icon.

The biography tells us that, when he had cash in his pocket (he borrowed frequently from friends and mentors), Noguchi drank heavily and frequented brothels while training in Tokyo (1). It confirms that he obtained the money to pay for his move to the United States dishonorably, by accepting three hundred yen from a family whose daughter he agreed to marry when he returned to Japan (2), which he never did. Finally, it confirms that, a few days before his departure, he insisted on treating his Yokohama colleagues to a grand banquet at Jimpuro, the famous brothel and “supposedly finest restaurant in Kanagawa Prefecture at the time,” which cost him nearly the entire 500 yen in his possession (3). This expense led Noguchi to once again beg one of his mentors for money to buy a ticket to San Francisco. He departed on December 5, 1900 (4). He traveled by train from San Francisco to Philadelphia; imagine doing that today. He was 24 years old. Coincidentally, 500 yen is the entry fee to the Noguchi Memorial Museum in his birth town.

The biography provided a plausible answer to my second question. I doubt that Noguchi and my ancestors met at the brothel, but they might have met through the job Noguchi held briefly in September 1899 as a quarantine officer in the port of Yokohama (5), where he was apparently the only officer who spoke English. A quarantine officer’s duties included meeting incoming ships to check their crews and passengers for communicable diseases. I know for certain that my grandfather was in Yokohama exactly one year earlier, and that he made additional trips there between 1898 and 1904, and perhaps until shortly before his marriage in 1909, but I don’t have any ships’ logs or other records from 1899 onwards. Shortly after his marriage, my grandfather retired from his seafaring life, considering it too dangerous given his family responsibilities (his first son, Peter’s father, was born nine months after his wedding). Ironically, life on shore proved more dangerous than at sea, as he and another of his brothers died in the second wave of the 1918 flu pandemic.

On April 10, 1912, Noguchi married Mary Dardis, whom he had met while in Philadelphia. Late in 1917, they decided to build a small cabin in the Catskills town of Shandaken, about ten miles west of where I now live, by a stream that I have to assume was the Esopus Creek. The biography has a photograph of this cabin, with its mountainous backdrop, but I could not identify its exact location today. Noguchi died from Yellow Fever in Accra, in the country known today as Ghana, on May 21, 1928. I was able to find his name on the passenger list of the ship that conveyed him from Liverpool, on the 2nd of November 1927, to Accra.

That’s my story, the first of several I’m hoping to tell.

Footnotes:

- Kita, Atsushi, Dr. Noguchi’s Journey: A Life of Medical Search and Discovery, (2003) pp. 82, 89-90.

- ibid. pp. 122 and 125

- ibid. p. 126

- ibid. p. 128

- ibid. p. 109