By Guadalupe Astorga

Last January 11, a human clinical trial in phase I caused brain death in one healthy volunteer, while five others were hospitalized. Unfortunately, this is not the only case where healthy volunteers have died or been severely affected.

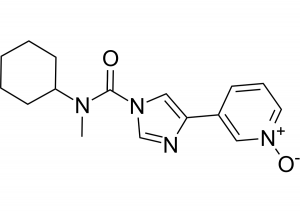

The molecule (BIA 10-2474) produced by the pharmaceutical company Bial, is an inhibitor of the fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), an enzyme that catabolizes bioactive lipids, including the endocannabinoid anandamide. The drug was developed as a therapy for anxiety and motor disorders associated with Parkinson’s disease, as well as chronic pain in people with cancer and other conditions. Other pharmaceutical companies have previously performed clinical trials to test the analgesic effect of other FAAH inhibitors with no signs of toxicity. However, these studies ended in phase II due to lack of drug effectiveness. Remarkably, the affinity of the inhibitor tested by Pfizer was 14,000 times higher than that of BIA 10-2474. This implies that the specificity of BIA 10-2474 to inhibit the FAAH enzyme is very low. Moreover, the molecular structure of BIA 10-2474 includes a highly reactive imidazole aromatic ring that can bind to other brain enzymes, including 200 other hydrolases with similar structure and whose activity is far from being understood. The investigation, led by the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (ANSM), has also shed light on a series of irregularities that occurred during the preclinical trials and were kept secret by Bial, as part of trade secrets. Conceivably the most serious among these is that according to the chemical structure of BIA 10-2474, it is most likely to be an irreversible inhibitor, rather than reversible as the company claims. This implies that even very small concentrations of the drug can irreversibly inhibit, not only the activity of the FAAH enzyme, but also the 200 other hydrolases present in the human brain. Considering this crucial information, it is inconceivable to understand how the trial design could comprise consecutive administrations of high doses of the inhibitor. This piece of evidence seems to be clearly related to the brain damage induced by the drug, as the severely injured volunteers were those who received only the highest doses of the drug. From sixteen groups of eight volunteers administered with increasing doses of BIA 10-2474, only five people were hospitalized after receiving repeated doses of 50 mg (almost the highest tested concentration). According to the ANSM report, this concentration is 10 to 40 times higher than that required to completely inhibit the FAAH enzyme. Indeed, extrapolation of the data taken in animals to humans, suggests that complete inhibition of FAAH is achieved with doses 20 to 80 times smaller than the maximal dose planned to be tested in humans (100mg). Furthermore, even after the first person was hospitalized, the other 5 still received one more dose the next day. The Report of the ANSM states that the mechanism of toxicity of BIA 10-2474 is clearly beyond FAAH inhibition and evidence of this subject needs to be presented by Bial Laboratory in future months.

Another critical piece of information that was kept secret by Bial is the number of animal deaths (including dogs and primates) during the preclinical trial. How could the drug be considered safe and approved to be tested in humans, if closely related animals died? Had the volunteers known this information, would they have taken the risk to test the drug?

Trade secrets can seriously block access to critical information obtained during preclinical trials performed in animals by pharmaceutical companies. It is astonishing that even scientists and institutions involved in the evaluation and approval of these dossiers cannot have access to some of the information. As a result, it is not surprising that important details are omitted by the pharmaceutical companies in order to start a clinical trial in humans.

In 2006, six healthy volunteers almost died during the clinical trial of the TGN1412 antibody. It was developed by the German company TeGenero to activate the immune system’s T cells. A few minutes after the drug infusion, all the volunteers suffered severe cytokine release syndrome leading to severe inflammation. In this case, the clinical trial went wrong because the drug tested in animals during preclinical trials showed strikingly different pharmacological properties when administered to humans. TeGenero omitted key differences between the amino acid sequence of the antibody receptor present in the animal model that was used during the preclinical trials (monkeys) and in the human sequence. These differences are crucial to predict how strongly TGN1412 would bind to the receptor in humans compared to the monkey cells. This was actually critical for the observed reaction in humans.

In 1993, five human volunteers died while two others required liver transplantation to survive during a clinical trial conducted by the National Institutes of Health. During the 13th week of administration of Fialuridine, a thymidine analog developed for its antiviral activity against the Hepatitis B virus, the drug induced severe hepatic toxicity and lactic acidosis. In this case, the preclinical trial performed in animals did not last long enough to assess the toxicity that was observed in humans only after the week 12th of drug administration.

Transparent and complete access to all scientific evidence and data is crucial to perform efficient evaluation of preclinical trials and further approval for drug tests in humans. Trade secrets in pharmaceutical companies have been shown to be extremely dangerous and represent a threat to human life in clinical trials. Rigorous legislation would guarantee complete data accessibility from experts evaluating the research done during all preclinical trials to protect the life of healthy volunteers in later phases of the trials.