Aileen Marshall

There has been much news coverage lately about the distribution of the new COVID-19 vaccines. Dr. Anthony Fauci mentioned a previous campaign to inoculate New Yorkers against smallpox in 1947, which supposedly covered six million people in just about a month. It was the last mass vaccine campaign in New York City. There are similarities and differences between these two incidents.

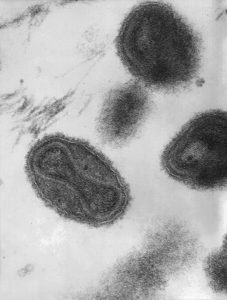

Smallpox, like COVID-19, is caused by a virus, in this case the variola virus. It is a DNA virus, a single linear double strand. It is unusual in that it replicates inside the host cell’s cytoplasm rather than in its nucleus. It also makes a unique DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and its outside is made up of Golgi body membranes, an organelle that is normally found inside a cell. Smallpox, like COVID-19, is transmitted through the air by droplets from an infected person coughing or sneezing. In some cases, although less likely, it can be transmitted by the used clothing or bed linens of an infected person. It presents as a full body rash that turns into blisters, as well as fever, body aches, and fatigue. There is no cure for smallpox, only management of the symptoms. While its mortality rate is 20-30%, people who survive smallpox are left with severe scars and sometimes blindness. It can only be definitively diagnosed by the detection of clusters of proteins called Guarneri bodies, from a skin biopsy.

The world experienced isolated outbreaks of smallpox like the one in New York City in 1947. On March 1 of that year, Eugene Le Bar, a Maine businessman, and his wife got off a bus from Mexico. They checked into a Midtown hotel and did some sight-seeing. He soon developed a fever and a rash and was admitted to Bellevue Hospital. Three days later, he was transferred to Willard Parker Hospital, the city hospital for communicable diseases at that time, on East 16th Street. His initial diagnosis was an adverse reaction to the drugs he had taken for his fever. But two days later, he died. On March 21 and 27 respectively, two other patients came in with similar symptoms who had been at Willard Parker at the same time: a 22-month-old girl from the Bronx and a 25-year-old hospital orderly, Ishmael Acosta, from Harlem. At that point, the Health Department began to suspect smallpox.

Israel Weinstein, the New York City Health Department Commissioner, received lab results that showed the presence of Guarneri bodies from Le Bar’s skin biopsy on April 4. He realized that the traditional Easter Parade was only two days away. With those massive crowds, smallpox could spread quickly. Along with Mayor William O’Dwyer, he held a news conference urging every New Yorker to get vaccinated. Even if you had gotten vaccinated as a child, he suspected that immunity may have waned. “Be safe, be sure, get vaccinated!” was the slogan. They immediately set up free clinics in hospitals, health departments, police and fire stations, and schools. They recruited volunteers from the health department, the Red Cross, off-duty police and firefighters, and the still existing World War II Air Raid Wardens to help run the clinics. The mayor received his injection on television. People lined up by the hundreds. There were only about half a million doses of smallpox vaccine in the city’s stockpile at first. Some doses were distributed to private physicians. Weinstein reached out to the seven smallpox vaccine manufacturers in the country, who promised around two million doses. He acquired another approximately 800,000 doses from the military, for a total of roughly three million doses. On April 11, The New York Times reported that 600,000 people had gotten their shot.

Carmen Acosta, Ishmael Acosta’s wife, died on April 13, the only other death in this outbreak. The story appeared on the front page of The New York Times. This drove people out to the clinics in greater numbers. The city’s tracking and tracing program concluded on April 15 that all of the traced contacts with Le Bar had been isolated or vaccinated. This practice is called ring vaccination. Some sources say that this is what eventually ended the 1947 New York City smallpox outbreak.

On April 16, the Times reported that the city had run out of vaccine doses. Police had to break up crowds who were told that there were no more shots after waiting in line. The next day, the city received another million doses from private labs. The Times daily tally on April 21 stated that a total of 3.4 million New Yorkers had been vaccinated. The next day, the tally was another 200,000.

The city declared the outbreak over on April 24 and started closing clinics two days later. The last clinic closed on May 3, and the city said that they had vaccinated six million people. If one adds up the daily counts from the Times, the total comes to 2.5 million. It is not clear which number is accurate, but the lower number is still an impressive feat in just one month. In the end, there were twelve confirmed infections and two deaths. The city had an advantage in 1947 as opposed to now in that the smallpox vaccine already existed, and only one shot was required. Smallpox was declared eradicated in 1980 by the 33rd World Health Assembly. As for COVID-19, as of January 14, 2021 the city had administered 303,671 shots since December 15, most of which were the first dose. The daily number of doses administered has been as high as 24,289. If this rate increases, and our vaccine supply is sufficient, it is possible that we may have all ten million New Yorkers vaccinated in a little over a year.