Gretchen M. Michelfeld

I am ashamed to say, my first attempt to explain white privilege to Beckett was only a few months ago. My son is almost twelve and I have been complacent, you see. I have practiced the complacency of a liberal urban mom who is reassured by the diversity of her neighborhood and schools, who has tried to teach anti-racist lessons from day one, who is pleased that her child has a diverse group of friends, happily accompanies her to protests, and asks for birthday donations to the American Civil Liberties Union.

I am aware of the virtue signaling in my opening paragraph. I am keenly aware of my white fragility: the defensive clinging to a belief in my fundamental goodness and fairness. I want to believe that I have taught Beckett to be good and fair.

But the shock of the recent racist violence in this country that has come into the foreground of white people’s collective consciousness has forced many of us to realize that we cannot talk about the evils of racism without acknowledging the privileges we enjoy. These privileges are a direct result of the perverted notion of white supremacy that first justified the economic calculus of slavery and segregation, and which continues (consciously or not) to dominate the thinking behind countless political and economic decisions every day.

So, while my son and I were taking a masked and socially distanced walk last month, Beckett brought up the horrible murder of Ahmaud Arbery, the young man from Georgia who was out for a jog and was hunted down like an animal by two white men who claimed they thought he was a burglar. “I can’t even understand it, mom,” he said. “How could anyone be that racist and evil?”

My first thought was one of shock and surprise. Frankly, I did not even know he was aware of Arbery. That is some privilege right there—believing I have the luxury of shielding my young male child from the ultimate horrors of racism. My second thought was the realization that solely teaching our white children that racism is immoral and being proud that they do not understand how racist violence is possible, is not doing them or their Black and brown peers any favors. While I recognize that being white has helped me in dozens of situations where I was in a jam and needed help from a stranger, it never occurred to me before that I am actually a complicit cog in the twisted wheel of systemic racism. How many lives has my complacency helped to destroy?

I looked him as much in the eye as I could, though our sweaty fabric masks fogged up our glasses, and I began a conversation about white privilege.

I told him about the time he was six and he pointed a toy gun at two policemen who laughed and pretended he’d shot them. Then I told him about Tamir Rice who was killed by cops the very same year as he also played with a toy gun. I told him about the time I horrified my non-white friends when I opened a bottle of cold brew coffee and took a swig while we waited in the checkout line. “What’s the big deal?” I asked. “I’m gonna pay for it. Do you want some?” “Oh GOD no!” they answered, “We’re good.” I asked him to imagine being a young Black man these days, needing to go to the store and needing to wear a mask. “But people know we all have to wear masks,” Beckett said, “they can’t assume someone is a criminal because he is wearing a mask.”

He had actually hit on an easy-to-explain aspect of white privilege—when you are white, people do not ascribe criminality to your everyday behavior or lethality to your resistance.

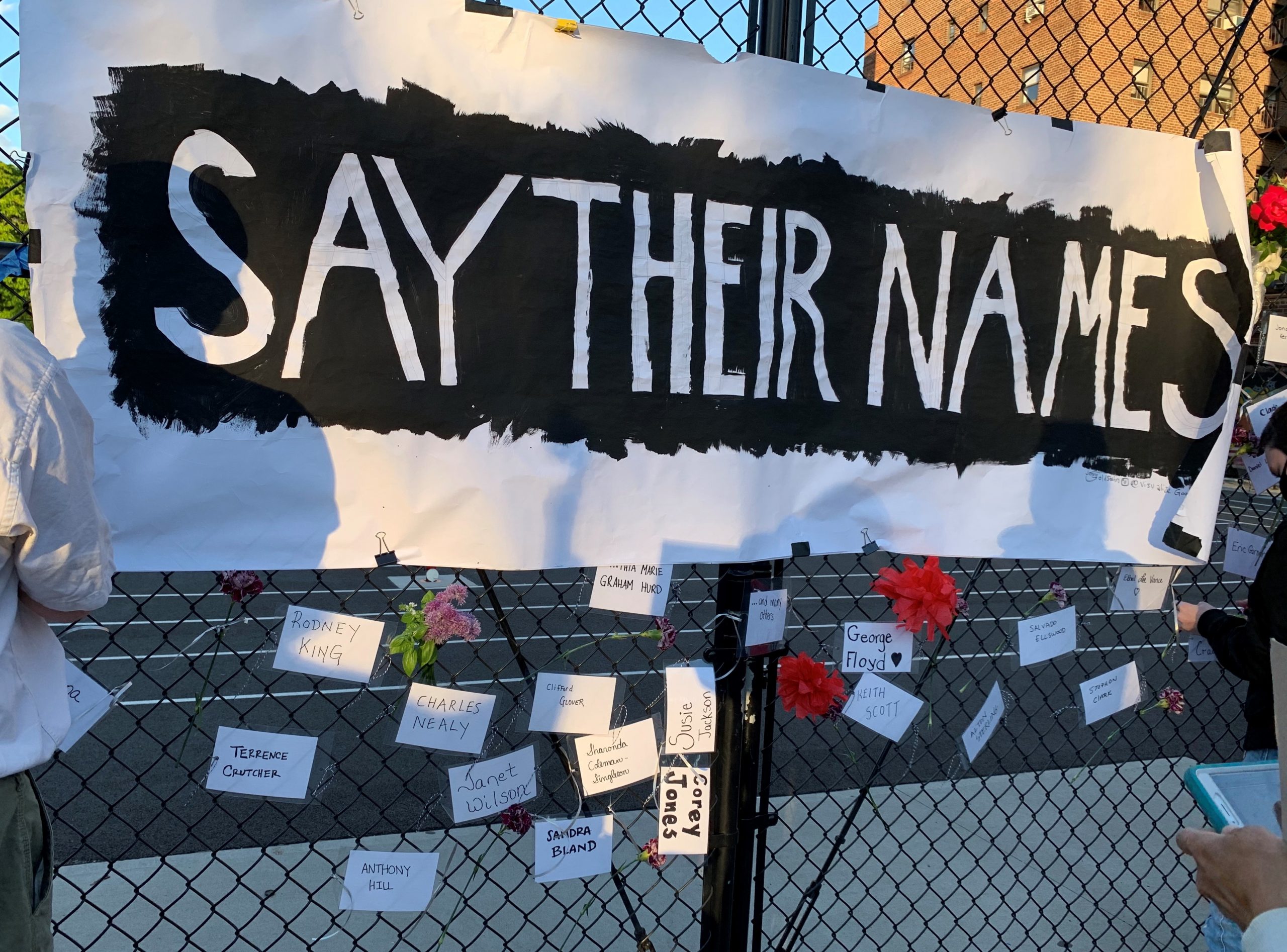

I told him that when I’m late for work and running for a bus, I know (if anyone even notices me) that people think, “Oh that poor lady is running late.” I asked him to imagine the decision a Black person must make if they are about to miss the bus. I told him about a Black woman I know who was on her high school track team and was stopped by the cops almost every time she tried to go jogging. I told him about a neighborhood mom he knows, who will not hang out on the corner and chat with friends unless there is at least one white woman in their group. “Why do you think that is?” I asked him. I told him about a political activist we know whose Black husband does not feel comfortable accompanying her when she is knocking on doors to get petitions signed. This was before the cold-blooded murder of George Floyd, but I told him about Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Stephon Clark…

“This is like the worst walk ever!” Beckett complained. He cried. He was angry with me. I apologized. I stopped talking.

I worry about overwhelming his already stressed-out-by-coronavirus brain. I worry that I will say exactly the wrong thing and he will tune out forever. I worry that I don’t understand what I’m talking about and that I will make things worse. But I must keep trying. We white people all must.

In an online school assignment last week, Beckett’s music teacher had the class watch five music videos about racism. He didn’t want to talk about them.

Today we are going to talk about them. Today might be too late, but it’s better than never.