Audrey Goldfarb

Individual action to fight climate change and habitat destruction is important. Plastic waste from just one person can have devastating consequences on wildlife, as exemplified by viral footage of a sea turtle with a straw stuck in its nose.

However, when considering the big picture, it is easy to feel powerless. How could the actions of one person influence the rampant and pervasive destruction of our planet? That single straw becomes much less meaningful in the context of the entire ocean. To significantly abate climate change at large, top-down policy changes are exceedingly more effective. Universal guidelines and initiatives incite cultural changes, which in turn demand more significant top-down policies. Both components are essential for progress.

Ainhoa Perez, a Research Associate in the Stellar Lab at The Rockefeller University, is an advocate for sustainability and personally leads a zero-waste lifestyle. She supports both individual and campuswide actions, but believes that neither are on pace with what the Earth is demanding. “There are things that can be done, but we are moving much slower than what we could and what we should,” Perez said. “We need support top-down from the university to provide the opportunity to do the right thing.”

Incentives from the government and from the university have been motivational in the past. The New York City Mayor’s Office of Sustainability launched the Carbon Challenge to encourage private institutions, including Rockefeller, to reduce their carbon emissions by 30% in ten years. Rockefeller joined the challenge in 2007, the same year the Sustainability Committee was established, and by 2019 the university had reduced emissions per square foot by 32%. “Some of the most impressive changes happened when the University got into a city-wide competition,” Perez said. “We were one of the first institutions to reduce carbon emissions, I think just because we had a challenge and had that as a goal.”

The success is largely attributed to a switch from oil to gas as a fuel source, in addition to the construction of LEED-certified buildings; in the last ten years, 33% of our campus received LEED silver status certification. The university is now committed to reducing its carbon footprint by 40% by 2025. However, Perez advocates for more ambitious goals. “One of the important things is for the university to commit to be zero waste and carbon-free,” she said. “It would make a huge difference just to have that as a goal.”

Alex Kogan, the Associate Vice President of Plant Operations and Housing Departments since 2001, is the driving force behind Rockefeller’s central sustainability initiatives. His efforts are focused on university-wide, quantifiable initiatives that benefit Rockefeller financially in addition to aiding the planet, such as using less fossil fuels and electricity. “Our approach has always been about carbon footprint reduction,” Kogan said. “We try to achieve this systematically campuswide. We can control the amount of heat content and cooling content we distribute to all buildings on a macro level.”

Rockefeller’s power house, which contains the heating and cooling plants, sits underneath the Rockefeller Research Building and Hospital Building. It provides heating throughout campus from the President’s house to Faculty House and Scholar’s Residence, and cooling to every building except for housing. Touring the massive facility leaves a lasting impression; slight adjustments to central heating and cooling—i.e. lowering the maximum temperature in the winter and raising the minimum in the summer—is a powerful and quantifiable mechanism to reduce emissions.

However, the practices of individual labs are up to the heads of labs and their lab members. “Laboratories are inherently terrible energy hogs because you can’t recirculate the air,” Kogan said. “For obvious safety reasons, laboratories require a certain amount of ‘air-changes’ in order operate. The best thing a scientist can do is to lower the setpoint in the winter and raise the setpoint in the summer.”

Some Rockefeller lab heads prioritize sustainability more than others. Daniel Mucida is a great example of this. “Daniel has been one of our biggest champions,” Kogan said.

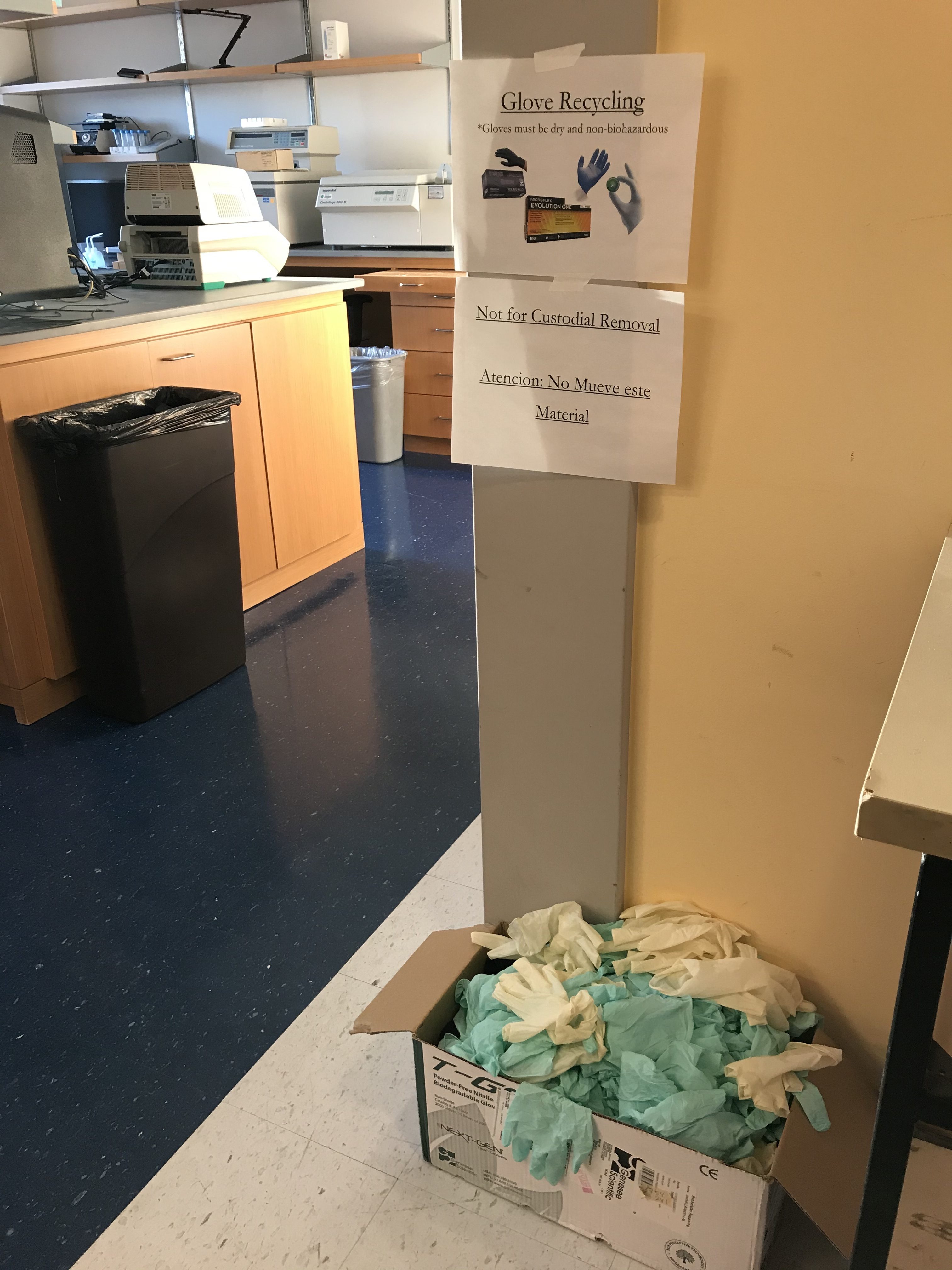

The Mucida lab reuses and recycles wherever possible. Ainsley Lockhart, a graduate fellow in the Mucida Lab, notes that these practices have little impact on the lab’s efficiency. “It probably takes me an additional ten minutes total per week,” she said.

Though these practices have been in place in the Mucida lab for ten years, few have followed suit to the same degree. “Not many labs do this,” Mucida said. “You walk around the labs and you want to have a heart attack because it’s so bad.”

Mucida was inspired to take action as a post doc at La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology after attending a meeting in Japan. He saw how efficiently and conscientiously the labs there functioned, and started advocating for his lab in La Jolla to do the same. However, it wasn’t until Mucida started his own lab that he was able to implement meaningful cultural changes. Now, he wants to fight for sustainable practices campuswide.

The use of disposable containers in the cafeteria is a big issue. Though the bottoms of takeaway containers are compostable, the lids are plastic. Neither are reusable, and both are superfluous. “I’ve been trying to change this for ten years,” Mucida said. “I wish there were zero disposable containers. I think people would adapt very easily.”

Habits become second nature quite quickly, and sustainable practices demand significantly less effort than most New Year’s resolutions. For most people, carrying a reusable container for lunch is much less challenging than committing to a workout routine. Central guidelines and regulations would expedite these transitions. Once green practices like proper recycling become part of the culture, it will be effortless to comply. “This is very simple,” Mucida said. “It should be like brushing your teeth.”

“Many people believe that those goals are very hard or impossible to achieve,” Perez said. “But that’s just because we got so used to this wasteful, single-use-based lifestyle. It’s so engrained in our routines that we tend to think that there are no alternatives.”

While reducing carbon emissions and other waste helps the environment and is financially advantageous, it is also personally rewarding. “It has a lot of benefits for the people working at the university,” Perez said. “It brings people together. We are the perfect place to be doing this because we already have a sense of community.”

Having Kogan lead central carbon emission policy has proven to be effective. These initiatives are organized, quantifiable, and growing. “We’re on the cutting edge of HVAC and electrical infrastructure, we have a very good idea what our peers are doing, and we’re well connected in the [academic] facilities community,” Kogan said.

However, there is no department at the university dedicated to reducing waste in the cafeteria, ensuring proper recycling, and educating scientists on sustainable lab practices. “The recycling here is a mess,” Perez said. “Nobody even knows how it works. All the bins look exactly the same. It is very poorly organized and advertised.”

There are a multitude of opportunities to improve, but the organized manpower to fight for them is limited. The students and postdocs that compose the Sustainability Committee move away from Rockefeller after several years, making it difficult to establish long-term plans. These members are also dedicated to their own research, which must take priority over membership to the committee. “It is all dependent on who is coming to the meetings and who is able to invest time and effort on these initiatives, which is not very much because we don’t have much extra time,” Perez said. “People come and go from the university. It’s important to have continuity and permanence of initiatives that are started.”

Another issue that many Rockefeller employees may be unaware of concerns the University’s investment options. “Our pension money is invested through a pension plan in fossil fuels, and there is no way to change that,” Perez said. “This is unbelievable. A research institution forcing their employees to give money to companies that are funding climate change denial?”

Though it will require substantial effort and cultural changes, Kogan, Mucida, and Perez are optimistic that Rockefeller can be a leader of sustainable biomedical research. “We need people to engage and to take action,” Perez said. “We can do it! It would be easy, it would be cheap, it would be better, it would be extremely impactful… and we have the responsibility to do it.”