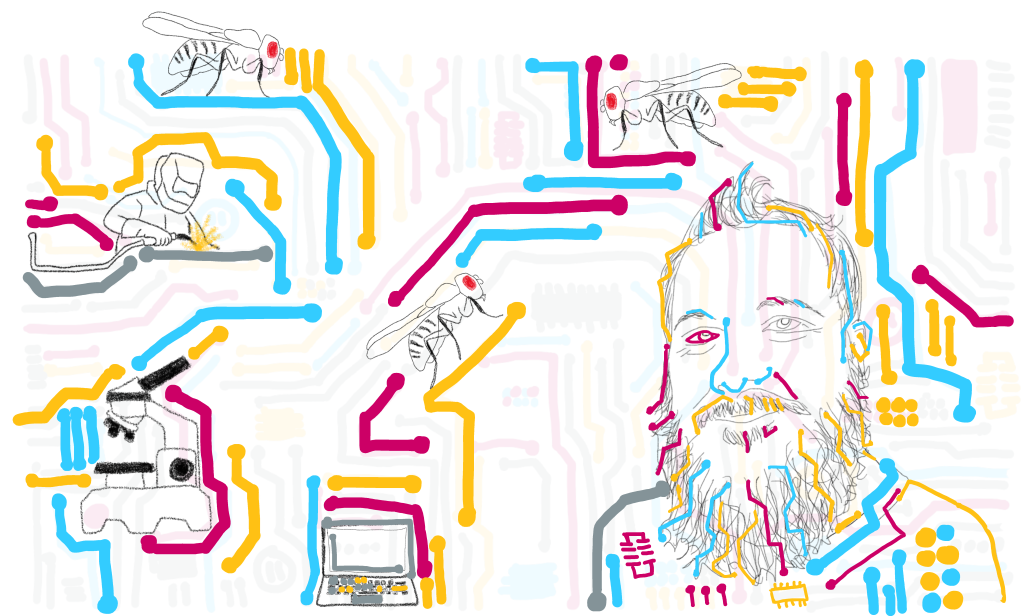

Jazz Weisman’s desk is in the far-right corner of Gaby Maimon’s lab at Rockefeller University, located on the third floor of Flexner Hall. You can recognize his desk based on the myriad of seemingly unrelated items on display: a series of intricate circuit boards and half-assembled custom electronics, a 3D-printed iPhone charging station, a cheat sheet for a Python data visualization library, and a 3’ by 2’ rustic cherry slab destined to become a kitchen counter. The only thing tying all of these unrelated objects together is that Jazz made them.

Jazz currently works as a hardware engineer at the Maimon Lab where he helps graduate students and postdocs design and build any custom equipment they might need for their projects. This equipment can be anything from a 3D-printed filter holder for a microscope to a custom temperature control system that heats fruit flies as they walk on tiny air-supported foam balls. “My job is basically just [to] help people build stuff so they can do their projects,” Jazz said. If you can name it, Jazz can build it.

Jazz’s friendly smile greets everyone who comes to his corner of the lab from beneath a big beard. At 6’ 1’’ tall, he can always be found wearing cargo shorts and flip-flops, even in the dead of winter, and t-shirts with science-themed puns. Before becoming the Maimon lab’s hardware engineer, Jazz was a graduate student in the lab. For his thesis, he wanted to look at what fruit flies do over the course of multiple days or even weeks. He was specifically interested in how they move around in the world—or, as scientists would call it, navigate. There had been multiple prior studies in the Maimon Lab, as well as other labs, on different navigational behaviors of flies over the timescale of minutes or even a few hours. No one had, however, looked at them for longer than that. This was largely because of a technical issue: no one really knew how to keep the flies alive for longer than a few hours while monitoring these behaviors.

To study navigation, scientists often fix flies in place by gluing them to little metal pins and by allowing them to explore virtual environments projected on LED screens by crawling on tiny, air-supported balls. These set-ups are very useful because scientists can design specific virtual environments for animals to move around in, but they come with a big downside: the fly can’t eat or drink while glued in place, so they desiccate and starve within hours. So, how can someone study what flies do over several days if you can’t even keep them alive for that long?

The answer Jazz came up with, in typical Jazz fashion, was to build something. He designed an entirely new system that allowed flies to be automatically fed while walking in virtual reality environments, keeping the animals alive overnight. The system even included automatic notifications that would appear in Jazz’s email every few hours with a snapshot of each fly, so he could check if they were still alive, and a randomly selected Shakespeare quote, to add a little whimsy. “Once I got one that was Help me, Cassius, or I sink! ” says Jazz, “and the fly was about to die, so I did need to save it.”

With this brand-new rig, Jazz discovered that flies walk in a consistent direction for days or, in some cases, even weeks. The specific direction they chose to walk in varied between flies, but a single fly seemed to choose its favorite orientation and stick with it. “The fact that flies can even do something consistently for so long was very surprising to us,” says Jazz. This behavior suggests that there could be memories in the flies’ brains that also last that long — something most researchers did not previously think would exist in fruit flies.

At this point you might be wondering: where did Jazz even learn how to build all these things?

Jazz Weisman grew up in Corvallis, a small university town in western Oregon. As a kid, he was interested in “building and designing stuff,” but wasn’t quite sure what that meant career-wise. His plan was to take a few years between high school and college to figure that out. The opportunity to do exactly that presented itself to Jazz the summer before his junior year of high school when he went to Burning Man with his dad.

Late one night, a few days before the main event started, Jazz was walking around the festival and ran into a group of people trying, and failing, to set up a plywood dome. He immediately offered to help and proceeded to spend the next several hours with his newfound friends assembling the structure. The group, very grateful for Jazz’s help, invited him to join them for the next week while they built an exhibit of 40-feet tall figurative art sculptures. At the end of the week of working together, Jazz had a job offer and a plan for what to do once he graduated.

Through this serendipitous Burning Man connection, at 17 years old, Jazz moved to San Francisco to work with a production company that built art sculptures for music festivals. Throughout his two years with the company, Jazz learned practical building skills like welding and building electronic circuit boards. From there, he went to work for a company that set up lighting for parties and concerts. Then he started working for a company that customized early electric cars to improve their battery life. In between those jobs, he was hired to sail a boat from Mexico to San Francisco.

Four years and several jobs later, in his early twenties, Jazz decided he was now ready to go to college. “I always assumed that eventually I would go to college,” he said, “but when I left high school, I really didn’t know what I wanted to do.” After years of working various engineering and construction jobs, Jazz now had a much better sense of what he wanted to do with his life.

“I love engineering, [but] most people who are engineers have jobs that don’t appeal to me,” Jazz said. “Sometimes you’re just overseeing the assembly of some giant thing. It’s like, okay, you’re building the giant thing, but you’re not actually soldering on anything.” He wanted to find a field of engineering with small enough projects that you still had a lot of creative control over the final product and a more direct relationship with the person for whom the product was designed. All the jobs that seemed to fit this description required a PhD in some scientific field. This led him to pursue a science undergraduate degree at Reed College, where he did several years of research in biochemistry.

After college, he was accepted to Rockefeller University’s PhD program, where he initially intended to study something related to chemical biology. This plan quickly changed when he saw a talk from Gaby Maimon in his first semester of graduate school. Gaby spoke about the fly like a little computer, trying to understand how its neurons might act as circuits performing computations. This approach appealed to Jazz. It analogized brains to the electronic circuits he was used to studying. “Plus,” he said, “they were building all this really cool fly-sized stuff, which looked like tons of fun.”

During his time as a PhD student, however, Jazz quickly realized that he enjoyed working on other people’s projects much more than on his own. “I think the biggest difficulty for me with a PhD was figuring out what I was going to do on my own project,” he said. “[That’s] just not a mode I work that well in. I’ve always worked much better with people than alone.” Jazz’s new post, as the lab hardware engineer, is the opposite of this kind of solitary work.

An average project Jazz works on in the lab usually starts with a lab mate showing up to his desk with a conundrum. They have an experiment they want to do, but the equipment they need to run the experiment doesn’t exist, something about their current setup is inconvenient, or a part of their rig is malfunctioning. Invariably, Jazz will have the answer. Sometimes it’s a design for a brand-new behavior set-up, which he will help build from scratch. Other times, it’s a clever little device that solves the inconvenience. Occasionally, it’s a couple of hours of his day trying to figure out why code crashes every time someone tries to run an experiment.

Sometimes, the person he is helping isn’t even from the Maimon lab. Jazz has assisted on the assembly of a tiny head-mounted mouse microphone for the Jarvis lab to record mouse vocalizations. He has set up one of his custom heating systems for the Vosshall lab to study mosquito heat attraction. He has shared his designs for a mini-projector system with the Ruta lab so they can study fruit fly visual courtship behaviors. If you attend a neuroscience talk at Rockefeller, chances are there will be some acknowledgment of Jazz Weisman at the end of the presentation.

His hardware engineer job gives Jazz creative control over the final product, the chance to work on problems that he finds intellectually engaging, the ability to build the things he designs, and the opportunity to interact with the person who is going to use his product. “I get to do science,” he said, “I get to work with people. I get to build stuff.” Exactly everything he imagined he wanted out of an engineering job. “What I’m gonna be doing 10 years from now, I still can’t tell you.” For now, if you want to build something for your experiments, Jazz is your guy.