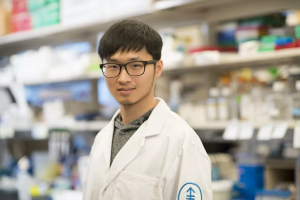

Hsuan-an (Sean) Chen is a joint postdoctoral researcher at Rockefeller University and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. He is currently working in the Charles M. Rice Lab, a lab focusing on virology and infectious disease, at Rockefeller University. He provides an expert cancer biology perspective on the pathology caused by the chronic Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), a liver-tropic virus that causes chronic damage and inflammation and ultimately culminates in the development of liver cancer. Of note, Chronic HCV infection is one of the most common causes of liver cancer in the US.

Current Projects in the Rice Lab

In the Rice lab, Chen is studying how chronic viral infection may lead to liver cancer development. He uses a virus called Norway Rat hepacivirus (NrHV), a close relative to HCV, that infects the laboratory mouse model. Chen is trying to understand the molecular mechanisms of how the hepatocytes transform into cancer cells in the context of chronic infection, as the details of this development remain unclear. Moreover, while HCV is already curable by Direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA), the limited accessibility of such drugs to patients, as well as the fact that cured patients can still get a later onset of liver cancer, underscores the unmet need to have a deeper understanding of the connection between HCV and cancer development.

Importance of integrating virology and cancer biology

Chen worked on liver cancer during his PhD, but previously focused on oncogenes activation and tumor suppressor loss, a more well-known and well-studied cause for liver cancer. In contrast, in chronic HCV-infected liver cancer patients, the cause of tumor development is still uncertain. The crosspath between virology and cancer biology makes this project particularly exciting as this is a largely unexplored field.

Viral epigenetic effects on liver cancer

People speculate that there is a viral epigenetic effect; that said, there are no obvious indicators for that. Testing the epigenetic hypothesis is problematic from the perspective of limited resources, as patients with tumors all have individual factors beyond laboratory control. HCV is a virus that only exists naturally in humans, and can take 20 years to progress from HCV infection to late-stage liver cancer. Thus, it’s difficult to pinpoint the drivers in the progression of the condition from virus to tumor. Small animal models where we can precisely manipulate individual factors are necessary. “If you have a mouse model, you could try to tease out the origin of the cancer, figure out when it starts, where it comes from, and how it transforms liver tissue to tumors. This is where the NrHV mouse model comes into play because it closely mimics the pathology of HCV human patients. We can now manipulate intervention and track the development of the tumor, carrying out mechanistic studies to nail down the underlying causes of tumorigenesis” Chen explained.

Challenges in the Rice Lab

There are a lot of challenges in this particular project, namely the time it takes for patients to develop cancer, which can take around 20 years. This issue is more or less the same case in mice, where it takes 1.5 years for cancer to develop. “Time is the biggest challenge. If you have aggressive liver cancer models that only last 3-4 months only, you may begin to question how closely it resembles HCV-associated liver cancer patients that take 20 years,” Chen said. However, it does offer some reassurance to have a genomically close animal model at the expense of having to wait longer than a simulated model that takes merely months. Chen had other ideas for solutions: “One thing I would do to expedite the process would be to introduce artificial oncogenes. We’re trying to find at what point those oncogenes actually speed up the tumorigenesis process. Nevertheless, everything still takes at least a year.”

Equity concerns also figure largely in HCV research. There is a new effort to cure viral infection by making antiviral drugs more available and affordable, especially because many HCV patients are of lower socioeconomic status. Additionally, curing a chronic HCV infection does not guarantee lower risk for liver cancer. “Even if patients receive antiviral drugs to stop the infection, it doesn’t always stave off the later onset of liver cancer. Even in the absence of viral infection they may still develop liver cancer in some cases. People are still trying to figure out the missing link and what will be the solution to this. Therefore, although there are antiviral HCV drugs on the market, we may still need a second line of treatment to apply in combination and prevent the cancer from setting in.”

Career Reflections

Chen has a unique perspective, coming from a cancer biology background and joining virology. He has called his work in the Rice Lab “one of the most exciting projects.” There is an appeal to having many fronts to explore. Coming from a cancer background where there are many overlapping interests and everyone has to find their niche in a very cancer-focused lab, the direction of research is narrower. In a virology lab, in which Chen is one of few cancer experts, he has a much broader range of study and exploration, facilitated by interacting and communicating with other scientists from a different area of expertise. It is these creative interactions that generate original ideas that can shape the new direction of projects. It opens many opportunities. This is the benefit of interdisciplinary research. A drawback of this, however, is when expert feedback is necessary but hard to come by. “Thankfully I am still collaborating with my previous lab and getting feedback from them. If you know what you’re going to do, a big lab [Rice Lab has 40 members] is a place where you can use your creativity to explore science in an interdisciplinary context.”

Chen also pitched that studying virology is a refreshing way to gain insight into the overall evolution of cancer. In virology, there are chronic infections that hijack the immune system like cancer cells that exploit the body’s environment. Tumors exploit previously beneficial resources and manipulate the faculties of the body to be harmful, creating a sort of “wound that will never heal.” When asked about how he was inspired to find his niche in cancer biology, Chen answered, “I came from a pharmacy background and spent most of my time studying drugs already invented in undergrad. However, I’m more excited about discovering something new and that’s why I landed on cancer research eventually. As cancer is one of the most flexible and ever-evolving diseases, there is no way to run out of questions. It intrigued me how cancer has been a major research focus for 5 or 6 decades without a universal cure being discovered.” This raised the question of whether the seemingly infinite progress possible in studying cancer is more demoralizing or inspiring to Chen. “Well you will never lose a job as a cancer biologist,” Chen chuckled. “What keeps you studying cancer also keeps you curious; you’re always finding something new. It’s almost a dream job of mine; to push scientific fronts relevant to human medicine.”

What Inspires Chen

Chen took a minute to try to come up with a single volume or work of art that translated to scientific curiosity. “As a teenager I read a lot of Scientific American. It was inspiring to see so many new scientific enterprises and the sheer expanse of options in science, even though I was not particularly interested in biology as a teenager. With those articles, I expanded my horizons and saw the opportunity in science. It made me wonder how many amazing things there are to discover. I had a subscription for 6-7 years in high school and undergrad and it’s one of the reasons I got into science.” The range of different types of science – biology, chemistry, physics… – that was featured in the journal particularly inspired Chen. “You never really know when something you read randomly might be useful in your own research.”

Chen joined the Tri-I for his PhD, coming from Taiwan nine years ago. “I think I’m lucky enough to be in this tri-institute area where you bump into professional scientists from every field, creating so much intellectual overlap. This is probably the best sort of place to do science; where you can find almost all different kinds of research.” With MSK being a sort of cancer guru, while neuroscience, immunology, and virology are based at Rockefeller, all you have to do is reach out, communicate, and collaborate. Chen values this institutional collaboration. It’s much harder to have a versatile approach while staying within one institution. Chen hopes to maintain the collaboration between the Tri-I systems as he forges ahead in oncological virology research.

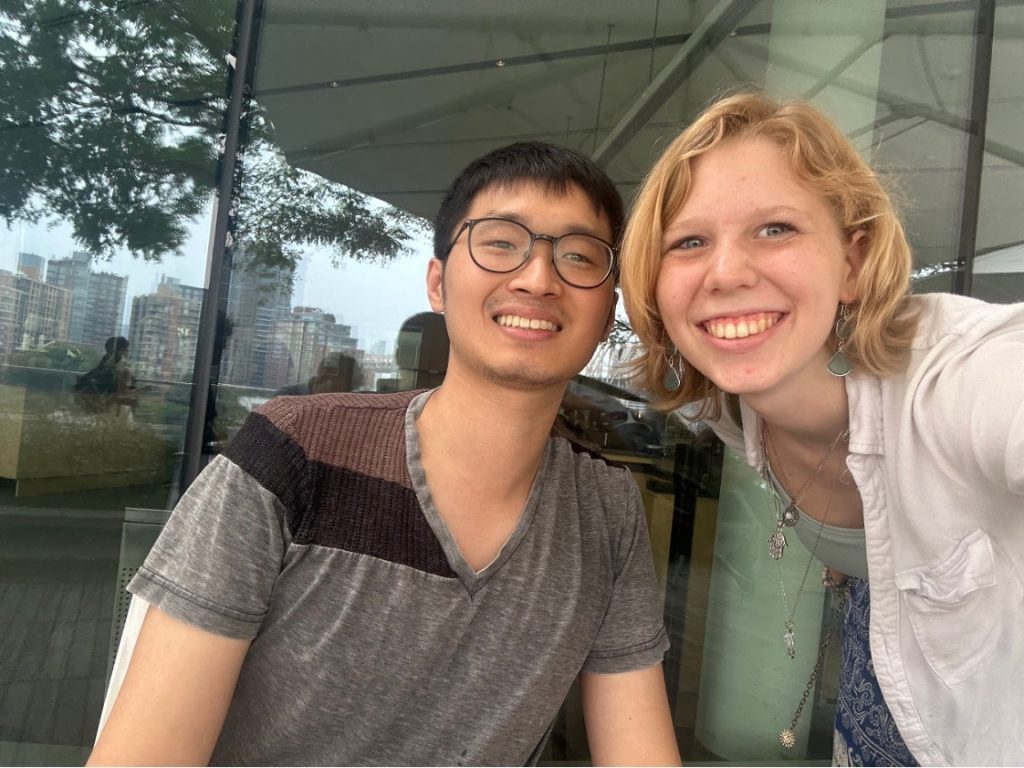

Photos provided by Hsuan-an Chen and Nina Skiba