By Bernie Langs

By way of introducing the highlights of my experiences with selected movies I watched in the summer of 2014, I am oddly reminded of the Roman Emperor Nero and the infamous popular image of him as the ruler who “fiddled while Rome burned.” The notion of Nero playing the lyre at a time of crisis can be traced back to the ancient biography of him by the historian Seutonius in his book The Twelve Caesars. It took only a couple of thousand years for the story to be diluted down to the image we now have and for it to become a metaphor for someone who dallies foolishly during a time of immediate crisis. The point is that the summer of 2014 was one of constant emergencies and tragedies on the international and domestic stages, some of which I wonder if the world will ever recover from. And yet, while our politicians avoided or, in most cases, just could not figure out viable solutions, the public, so very emboldened (and deluded) by the idea that the ballot box gives them power, also sat back and could not truly and in a meaningful way, engage. My own personal fiddling was scored by the following flicks.

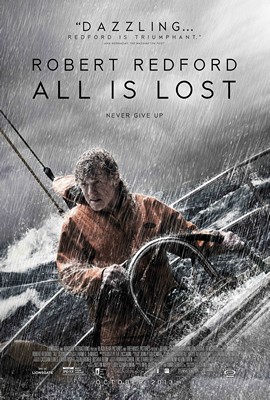

This summer, the big studios poured out yet more comic book epic films and other banal entertainment with big bright explosions. This allowed my stretch of not actually going to a movie theater to reach a life-long record length of time. Yet, I was able to find some recent film nuggets to watch On Demand on stunningly detailed HD television or downloaded on my hand-held Kindle Fire device. Films that present the story of an isolated individual facing a near impossible situation and either persevering or perishing in a gallant tale of courage have always appealed to me. Two movies I watched this summer examine this bravery and both did it extremely well. Robert Redford is the sole actor in All is Lost and how he was not nominated this year for an Academy Award as Best Actor for this performance will remain a mystery in perpetuity [Editor’s note: though Jim Keller’s “For Your Consideration” column may shed some light on that]. Redford was in the 1972 film, Jeremiah Johnson, about a 19th century American who takes to the snowy mountains to leave civilization behind and ends up facing everything from attacks by Native Americans to bears. The title character’s solitude as portrayed by Redford is best summed up at its end, where Johnson is reunited with a like-minded elder mountain man and he sorrowfully says, “I wonder what month it is.” All is Lost takes place in the present and there is almost no dialogue in the whole film aside from the tearful, regret-filled prologue speech. It’s the story of Redford’s unnamed character on a boat, in the middle of the ocean, and his struggle to stay alive and afloat after he is awakened to find a hole in his ship made from striking a large, metal container used to export goods. It’s a fantastic nuanced fight that he displays and the movie builds to an excellent and thrilling finish.

This summer, the big studios poured out yet more comic book epic films and other banal entertainment with big bright explosions. This allowed my stretch of not actually going to a movie theater to reach a life-long record length of time. Yet, I was able to find some recent film nuggets to watch On Demand on stunningly detailed HD television or downloaded on my hand-held Kindle Fire device. Films that present the story of an isolated individual facing a near impossible situation and either persevering or perishing in a gallant tale of courage have always appealed to me. Two movies I watched this summer examine this bravery and both did it extremely well. Robert Redford is the sole actor in All is Lost and how he was not nominated this year for an Academy Award as Best Actor for this performance will remain a mystery in perpetuity [Editor’s note: though Jim Keller’s “For Your Consideration” column may shed some light on that]. Redford was in the 1972 film, Jeremiah Johnson, about a 19th century American who takes to the snowy mountains to leave civilization behind and ends up facing everything from attacks by Native Americans to bears. The title character’s solitude as portrayed by Redford is best summed up at its end, where Johnson is reunited with a like-minded elder mountain man and he sorrowfully says, “I wonder what month it is.” All is Lost takes place in the present and there is almost no dialogue in the whole film aside from the tearful, regret-filled prologue speech. It’s the story of Redford’s unnamed character on a boat, in the middle of the ocean, and his struggle to stay alive and afloat after he is awakened to find a hole in his ship made from striking a large, metal container used to export goods. It’s a fantastic nuanced fight that he displays and the movie builds to an excellent and thrilling finish.

Gravity was surprisingly engaging as well, with Sandra Bullock portraying an astronaut in crisis out in space with nothing but her wits and the advice of a Buzz Lightyear-type, George Clooney to pull her through. The final two minutes had me thinking that this was a new generation’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. That film, masterminded and directed by Stanley Kubrick from the book by Arthur C. Clarke, was more subtle, and left its audiences wondering what in hell it all meant. Gravity finishes with an oddly Kubrick-like flair, yet it is an ending meant for a 21st century audience that likely won’t think about its implications for hours or years to come, the way I did after I saw 2001 at a film revival house theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1980.

Tim’s Vermeer was another fine film I watched this summer. The entertaining and sometimes frightening comedy duo Penn and Teller created this documentary about how software maven, Tim Jenison persists over years of preparation and months of actual painting to produce a replica of a detailed Johannes Vermeer painting. Jenison, who is not an artist and had never painted before, creates an optical device using only materials that were available centuries ago in Vermeer’s time. He seems to prove his theory about how Vermeer was able to paint in such minute detail, which is beyond the scope of what the human eye can actually see. Vermeer could only have done so with the aid of a mechanical device like the one Jenison builds. But he doesn’t stop there. Jenison physically recreates the room depicted in the painting, from the tapestries to the furniture to scale. He even makes his own paints, using only materials available in Vermeer’s time. The film entertains because Jenison, though brilliant, is human, and his gargantuan task often leads to bursts of frustration, many of which are funny and amusing. But his patience and persistence gives the film its passion and leaves one with a lesson of the satisfactions of succeeding with personal tests of endurance.

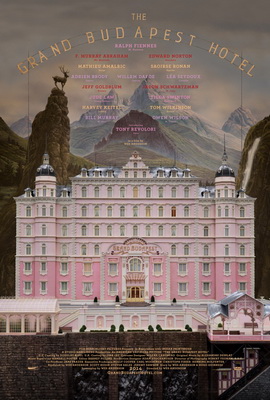

I had high expectations for Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel—especially since I recently discussed his movie, The Darjeeling Limited with high praise. I wasn’t disappointed. In this surreal fable-like movie, Ralph Fiennes plays the concierge of a fictional hotel in a fictional country with incredible humor, refinement, and with a keen sense of adventure. Similar to Woody Allen, it appears that actors are anxious to work with Anderson, and the cast includes some of today’s better film personalities. One expects Bill Murray, Owen Wilson, and Jason Schwartzman to make their usual appearances, but there are many surprise stars, including an almost unrecognizable, yet characteristically tough, Harvey Keitel. The tale, told in flashback, takes place mostly in the early 1930’s and Fiennes’s character, Gustave H., is the consummate Old European hotel concierge, who is teaching a young bellhop protégé the ropes of pleasing the most demanding of Old World wealthy guests. The movie reaches hysterical and improbable levels of convoluted plot twists and diversions, all of which are a pleasure to watch unfold and resolve. Ralph Fiennes’s previous roles include the mob boss in 2008’s In Bruges—his entrance towards the end of that movie is a wonder of hilarity mixed with a dangerous persona. He reaches new heights of subtle comedic touch in Budapest. I loved listening to his vocal inflections throughout this performance.

I had high expectations for Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel—especially since I recently discussed his movie, The Darjeeling Limited with high praise. I wasn’t disappointed. In this surreal fable-like movie, Ralph Fiennes plays the concierge of a fictional hotel in a fictional country with incredible humor, refinement, and with a keen sense of adventure. Similar to Woody Allen, it appears that actors are anxious to work with Anderson, and the cast includes some of today’s better film personalities. One expects Bill Murray, Owen Wilson, and Jason Schwartzman to make their usual appearances, but there are many surprise stars, including an almost unrecognizable, yet characteristically tough, Harvey Keitel. The tale, told in flashback, takes place mostly in the early 1930’s and Fiennes’s character, Gustave H., is the consummate Old European hotel concierge, who is teaching a young bellhop protégé the ropes of pleasing the most demanding of Old World wealthy guests. The movie reaches hysterical and improbable levels of convoluted plot twists and diversions, all of which are a pleasure to watch unfold and resolve. Ralph Fiennes’s previous roles include the mob boss in 2008’s In Bruges—his entrance towards the end of that movie is a wonder of hilarity mixed with a dangerous persona. He reaches new heights of subtle comedic touch in Budapest. I loved listening to his vocal inflections throughout this performance.

Like Jesus’s miracle of turning water into wine at the wedding at Cana (as noted in John’s Gospel) I have saved the best for last. I have quite the soft spot for British humor since the days of stumbling on the U.S. premier of Monty Python’s Flying Circus in the mid-1970s, where one would have least expected to find such irreverence. The 19th century art critic John Ruskin said something along the lines of “in the face of the most gorgeous sight of countryside an Englishman will not pause to make a wise-crack.” The other day I heard a musician note that the British are unique in their deep-set humor to the point that they would allow appropriate and accepted jokes at “a funeral of triplets.”

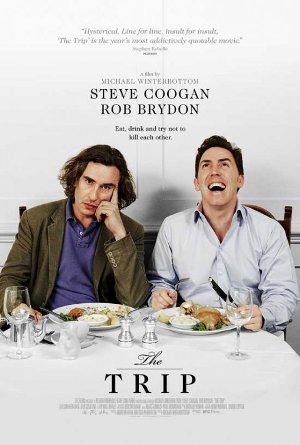

My wife alerted me to The Wall Street Journal review of the new movie The Trip to Italy. Discovering that it was a sequel, we tracked down the first film, The Trip, made for the BBC in several episodes in 2010 and released later that year as a feature film. The Trip follows Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon playing versions of themselves through a tour of north England restaurants Coogan is to review for a British publication. The absolutely stunning countryside is depicted matter-of-factly, as are so many great cinematic views of small English towns and their varying historic remains. Coogan and Brydon were about 40 years when filming, and while watching I had the thought that the British version of the immaturity of the modern male adult is more mature than his American counterparts. Then, Ben Stiller, Hollywood poster boy for childish antics appeared in a dream sequence. Coogan and Brydon riff throughout their car rides, meals, and hotel stays with incredible wit, erudition, and silliness. They make one laugh by reciting classic English poets or by attempting to out-imitate each other with impressions of veteran Brit talent, Michael Caine. Brydon notes and demonstrates, quite hysterically, in his impressions of Caine, the subtle difference in inflections of the early Caine and the old Caine. The biggest problem with The Trip is that I laughed so hard during some of their fast-paced attempts to one-up each other, that I missed a lot of dialogue. My wife told me that her friend watched the movie a second time with subtitles, so as not to miss any lines.

My wife alerted me to The Wall Street Journal review of the new movie The Trip to Italy. Discovering that it was a sequel, we tracked down the first film, The Trip, made for the BBC in several episodes in 2010 and released later that year as a feature film. The Trip follows Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon playing versions of themselves through a tour of north England restaurants Coogan is to review for a British publication. The absolutely stunning countryside is depicted matter-of-factly, as are so many great cinematic views of small English towns and their varying historic remains. Coogan and Brydon were about 40 years when filming, and while watching I had the thought that the British version of the immaturity of the modern male adult is more mature than his American counterparts. Then, Ben Stiller, Hollywood poster boy for childish antics appeared in a dream sequence. Coogan and Brydon riff throughout their car rides, meals, and hotel stays with incredible wit, erudition, and silliness. They make one laugh by reciting classic English poets or by attempting to out-imitate each other with impressions of veteran Brit talent, Michael Caine. Brydon notes and demonstrates, quite hysterically, in his impressions of Caine, the subtle difference in inflections of the early Caine and the old Caine. The biggest problem with The Trip is that I laughed so hard during some of their fast-paced attempts to one-up each other, that I missed a lot of dialogue. My wife told me that her friend watched the movie a second time with subtitles, so as not to miss any lines.

I began this column with the gloomy image of the matricidal madman Nero fiddling as his world burned and likened it to our own inability to fix the complex problems we face today while spending time watching movies. Yet, I will not leave you adrift like Robert Redford and Sandra Bullock. Let us remember, though to be honest I can’t come close to recalling the actual phrasing, the lesson taught in ancient China: Fix (rectify) your family, and then you can fix your village; fix your village and then you can fix your nation; fix your nation and then you can fix the world.