Bernie Langs

There are four superlative film documentaries, two released in 1970 and two this year, chronicling music festivals that reflect era-defining moments in the cultural and social history of this country. Opinions stretch far and wide as to what lessons can be learned from each of these movies and whether each film is indicative of a deeply rooted, underlying psyche of what it means to be American. The documentaries inspire their viewers to delve deep into ideas about the music itself, specifically the theory of whether or not the art is selfishly shaped and advertised in a destructive package created for the consumerist corporate exploitation of young people, which subsequently “trickles down” to the broader population through many mediums.

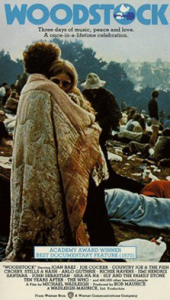

The original Woodstock Festival was held over three days in mid-August 1969 on a farm located in Bethel, New York. Film director Michael Wadleigh released a movie about the “celebration,” Woodstock, in March 1970, featuring three hours of footage of the extravaganza attended by over 400,000 people, spotlighting selected extraordinary performances by major rock, folk, and soul acts of the decade. There are interviews with attendees, festival workers, views of drug-taking and river-bathing young people, as well appearances by local shop owners and residents of the small town deluged by crowds of counterculture, young “hippies.”

The greatest moments of the 1969 Woodstock festival are the ethereal performances of Santana, The Who, Jimi Hendrix, Crosby Stills and Nash, Ten Years After, Richie Havens, Arlo Guthrie, and the soulful, peace-loving, rocking extravaganza of Sly and the Family Stone. The peak of the three days may be the performance of Sly and the Family Stone, a huge, racially integrated band with horns, pianos, guitars, and percussionists, as they undergo the call and crowd response of “Want to Take You Higher!”.

Directors Albert and David Maysles, masters of documentary storytelling, followed the 1969 American tour of The Rolling Stones with cameras and crew in hand and presented their footage as Gimme Shelter released in December 1970. Viewers are treated to entire songs played by the Stones at Madison Square Garden with additional scenes of them mixing songs such as “Wild Horses” at the famed Muscle Shoals studio in Alabama. The viewer is also privy to the planning of a Woodstock-like festival near San Francisco by lawyers and music managers as they search out a venue where hundreds of thousands will gather for the event. What we really are bearing witness to in these shots are the calm drawing up of blueprints for impending disaster.

The top-bill act at Altamont Speedway on December 9, 1969, was The Rolling Stones. The festival, once marketed as California’s opportunity to display to the country its moment of peace and love, devolved over the day of music into mayhem. The security force to “police” the crowd was the notoriously violent biker group, the Hell’s Angels, who almost immediately set out to beat up out-of-control drug-taking audience members. The violence culminated in the stabbing death by an Angel of a young man waving a (possibly unloaded) gun during the song “Under My Thumb” as the Stones played through the night to an out-of-control crush of festivalgoers. Amazingly, in the darkness and through hundreds of people in the crowd near the stage, the Maysles accidently captured the very moment of the killing. The footage in Gimme Shelter would later be used to acquit the biker of murder in court, since the outline of the waved gun is on view for about two seconds against a white background in the night in a moment of disturbing blurred fury.

For decades, Altamont was considered the moment that the peace and love movement of the 1960s came to a dead stop, exposing how tenuous and unrealistic the idealism of an entire generation had been all along. Pundits, from music and cultural critics to editorializing observers of history, held The Rolling Stones responsible for the tragedy of what occurred and their sound as representative of the worst instincts of a society’s darker personality, which could not help but lead to violence and the metaphoric death of the extended 1967 “Summer of Love.” I say emphatically to all such accusations, “rubbish.”

In 2021, two new music festival documentaries, mirroring in some ways the juxtaposition that occurred in 1969 between Woodstock and Altamont, were released, also a contrast between good vibrations as opposed to unhinged violence. The musician Questlove recently released his film, Summer of Soul, on the Hulu streaming service and in theaters. The film documents six afternoon concerts held in Manhattan’s uptown area of Harlem, also in 1969, that never received press or attention over the years despite appearances by numerous performers who were at the top of the music charts and their fame at the time, including some who had also appeared at the Woodstock festival.

Sly and the Family Stone, as at Woodstock, delivered the greatest performances in Summer of Soul. Early in the documentary, we’re treated to their hit, “Everyday People,” and towards the film’s end, we listen to the very song they played at Woodstock, with the same crying out of “Wanna take you higher – HIGHER.” It is a congregational bliss of soul and boundless love, captured in both Bethel and in Harlem. Other great moments in Questlove’s film include music by Stevie Wonder, The 5th Dimension, Gladys Knight & the Pips, The Staple Singers, and the legendary Nina Simone and Max Roach.

In addition to the extraordinary and delightful music of the film, through interviews and the many shots of the crowd, the festival comes across as more honestly “feel good” and peaceful without the pretensions of other concerts at the time. As the film pans across the crowd over the six days, there isn’t one individual obviously drunk or high or behaving in the embarrassing uncontrolled manner on prominent view at the more famous 1969 gatherings. At the Harlem Festival we see old and young African Americans, many together as families, enjoying a day in the park, grooving to the vibe of the sublime music while connecting emotionally and spiritually with the performers. Also in the crowd is a mix of Harlem’s Spanish population and white men and women calmly laughing, dancing, and smiling in joy as they take in the music. The fact that no television network or film studio chose to air the footage of the festival for decades, depriving us all of viewing the concerts, becomes an essential focus of the movie. As a glaring example of overt racism, many of the performers and attendees interviewed by Questlove for Summer of Soul examine how the Harlem festival speaks to the harsh climate for people of color in the U.S. at the time and ponder why so many related problems unbelievably and terribly persist to this day.

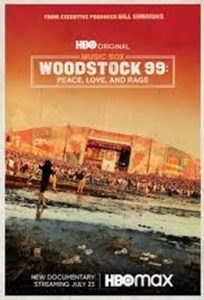

Woodstock ’99 was released in July 2021 on the HBO Max network and is the story of how the music and performers at the Woodstock 1999 festival incited horrific violence, with attendees egged on by the aggressive, screamed speeches and singing by several bands amid a pounding, deafening “call to battle” of guitars and drums. If Altamont was a nightmare from which America woke up to realize that their youthful utopia had all along been a grotesque dream and a sham, Woodstock ’99 unveils the cemented foundation on which a tower of blind, violently conceived ignorance remains unshakably solid in our culture. It’s rare that a societal documentary can sicken its audience more than any fictional horror flick. The festival was billed as a reprise of the original Woodstock’s peace and love purpose, but the mostly young, white men weren’t having any of that from the moment they hit the boiling hot venue on those July days in 1999 in Rome, New York. Several attendees died of heatstroke, women ended up being savagely groped by crowds of young men, and a few women were raped by crazed twenty-somethings feeding on music of unashamed and unabashedly pure hatred.

On the last evening of the festival, concertgoers took the candles distributed for a nighttime vigil against gun violence to set alight anything flammable they could find for massive bonfires, as they tore down metal towers holding equipment for the show. At one of the worst moments of out-of-control rioting in the documentary, the band The Red Hot Chili Peppers was quietly asked by the promoters to calm the crowd, but instead vocalist Anthony Kiedis chose to literally “fan the flames” by leading an improvised, manic version of Jimi Hendrix’s song “Fire.”

Much of what is commonly believed about the original Woodstock is a mythologized retelling of what actually happened, a point brought up again and again by commentators in HBO’s Woodstock ’99 documentary as they deconstruct what went so wrong at the later remake. However, it is undeniable that the performers and singers in 1969 did grab hold of peaceful feelings abounding in the air. Viewing the late 1960s crowds at Woodstock and the attendees at Altamont, perhaps it’s simply a matter of East Coast versus West Coast lifestyle and attitude. Some of the hippies at Bethel were high or drunk, but there was no expression of repressed frustration boiling over. At Altamont, the Californians on display are often so inebriated or zonked out that they stumble like zombies around the grounds, inciting anger and annoyance by those they smash into. The Hell’s Angels absurdly and horrifically took this behavior as an opportunity to beat concertgoers as they pleased. When The Rolling Stones hit the stage that night, an entire day of fighting culminated in violence taking place directly upfront near the band and in view of the Maysles’ many cameras. Altamont didn’t end the 1960s, it was where the bummer, bad trip of an indulgent drug culture met the fists of lunatics whose lives centered around motorcycles and beer.

The underlying causes of the vile behavior we witness in the documentary, Woodstock ’99, remain alive to this day, a legacy of unnecessary hatred exploding in actual destruction. One could postulate that the young men at the concerts, constantly described in the documentary as “morons,” “idiots,” and “numbskulls,” grew up to storm the U.S. Capitol building on January 6, 2021. Most of what we listen to by the bands in the movie is a disgrace to the very name of “music” as several performers yell and scream abusive and obscene “disgust of life” tirades. It resembles a call to arms to a brotherhood centered on vague, simplistic principals that expressing uncontrolled rage is legitimate and necessary. Young people at times plummet towards hopelessness when taught to believe that they are viewed in American society as a dumb-luck group with no chance from birth for happiness or meaningful employment. Woodstock ‘99 shoulders the historic shame of Altamont with none of its remorse, regrets, or lessons learned. Bands such as Korn, Limp Bizkit and their low-grade, imbecilic vocalist, Fred Durst, and the right-wing, shamelessly untalented Kid Rock, encouraged their fans to embrace destruction of the “system” that has designated them “useless.”

Music promoters, many bands, and numerous corporate concert sponsors have hung on to the selling point that spending one’s life with adolescent desires and attitudes is the best approach to combat aging. In actuality, that is nothing but a lazy, ignorant, and childish philosophy. Woodstock ’99 couldn’t pretend to be revolutionary with its simple-minded credo of “I’ll do whatever I want, whenever and wherever I want, and no one can stop me.” Societal encouragement, from music to the airbrushed, “ideal” youthful beauty displayed in magazines and commercials to film and TV shows, are all promoting a youth culture attitude allowing us to only select in our lives from the rankest, lowest-hanging spoiled sustenance. One must see it for what it really is when exposed to the bright light of truth: banal, absurd posturing in defense of never becoming an adult who must handle a multitude of difficult choices, responsibilities, and perhaps most frightening of all, transitioning to emotional growth that allows deeper understanding and enrichment of life and love. Viewing Woodstock ’99, one discovers how such senseless, superficial beliefs continue to pervade the minds of so many people, with no end in sight for the future. Until we embrace and enjoy the notion that growing up and growing older carries us to our best selves and the most fulfilled life, the mindset of uncontrolled lifelong adolescent frustrations will remain a clear and present danger to discovering a plane of “higher” physical, philosophical, and mental health in America. Sly and the Family Stone express it beautifully at the original Woodstock and the Harlem Summer Festival: Wanna take you higher – HIGHER!