Bernie Langs

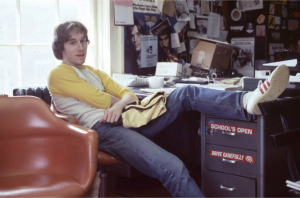

Jonathan Klein is the former President of CNN/U.S., having filled the position from 2004 to 2010. A 1980 graduate of Brown University, his interest in media and news started at the respected student-run commercial radio station in Providence, Rhode Island, WBRU-FM, where he worked as news director and, eventually, general manager. He began his professional career in television news in 1980 at a Providence-based station and by 1982 was working as a writer and news editor for Nightwatch at CBS News. Over sixteen years as a producer for several CBS News broadcasts and documentaries, Klein eventually rose to executive vice president, overseeing prime time programming including 60 Minutes and 48 Hours.

Klein has won multiple Emmy, Peabody, and DuPont-Columbia Awards for outstanding news and documentary coverage.

A serial entrepreneur who founded the first video aggregation site, The FeedRoom, after leaving CBS, Klein has launched and run several media/tech ventures since his CNN tenure, including TAPP Media and Vilynx. He serves on public and nonprofit boards of directors, is a consultant for the hit HBO series Succession, and currently is developing the new nonprofit, Unite, with Timothy Shriver and others.

During his tenure at CNN, Klein changed the direction of how cable news networks and other news outlets report the most important issues and stories facing America and the world. Klein answered questions via email for this interview:

Bernie Langs: In 2008 you spoke about the growth of integration of user content and how producers had been forced “to think multi-platform in everything they do,” observing “it doesn’t matter how good your content is if no one is going to see it.” Your ideas may be truer than ever and seem prophetic in hindsight. This balancing act between advertising revenue, adapting content to user platforms across demographics, and packaging the news so it gets noticed—would you agree that in the end, the raw, objective story cannot help but suffer in some way, when news becomes another commodity?

Jonathan Klein: I think the past four years have demonstrated the exact opposite—that the unadorned, cold, hard truth shines through no matter the platform it is delivered on, and cuts through the clickbait more effectively than any gimmicky gif. Look no further than the brilliant reporting on the Trump Administration by TheNew York Times and The Washington Post—people lapped it up eagerly whether via Maggie Haberman tweets or Phil Rucker appearances on cable or the digital or print editions of those papers or the books that some reporters published. The more noisy nonsense is out there, including chaff purposely scattered by deceptive politicians and apparatchiks, the more news consumers hunger for reliable information, in whatever form they can get their hands on it. That’s why those outlets are seeing such a boom in their business, even getting people to pay for content that they’d been used to accessing online for free. Fresh information from a trusted source is the opposite of a generic commodity—it has proven to be more vital than people had realized.

BL: One of the first things you did at CNN in 2004 was deploy an unusually large number of U.S.-based correspondents to cover the Boxing Day tsunami in Asia instead of using local reporters. It became CNN’s strategy for other major stories as well. What concerns me is that over the years, the major cable all-news stations stick to one story obsessively for many days, repeating “breaking” reports or devolving into minutia that isn’t classically “news worthy.” Has this phenomenon known as “flooding the zone” morphed at CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News into around the clock U.S. political coverage that leaves no room for extensive international news coverage?

JK: The idea behind flooding the zone was to leverage CNN’s advantage in field reporting and analysis—we had vastly more skilled reporters, producers, and photojournalists to commit to stories around the world than our competitors, which meant that we could provide depth and insight on important stories that the others couldn’t, stories such as the Haiti Earthquake and Gulf oil spills, where we deployed more people faster, and stayed on the story weeks and months longer, than any other television or digital news organization. We won Peabody and Emmy Awards for that in-depth coverage, and to this day I’m so proud of our teams that took such personal risk and threw themselves into revealing dimensions of those stories that no one else did or could. That same approach could be applied to political coverage if the networks chose to abandon horse-race coverage that obsesses over political strategy (which 99% of viewers do not care about) or polling (which has been thoroughly discredited now) and instead focused on the impact of policies on peoples’ real lives—flood-the-zone coverage on the pandemic, or systemic inequality, or solutions for reviving the economy, would be fascinating to watch because they would be so much more relevant to viewers’ lives than the Beltway inside-baseball or Trump tweet du jour coverage. As a result it would generate higher ratings. We know this because this is closer to the NPR approach, and they get thirty million listeners per week, which the networks would love to have.

BL: One of your accomplishments was to end programs at CNN that had overrun their course, such as Larry King’s show and Crossfire. Yet, some of what King had become remains all over television and the bickering, ridiculous Crossfire model is equally prevalent. Was your intention to stem the tide of shows like these because they represented a trend of lowering standards in cable news?

JK: One of the reasons I had been hired to run CNN/U.S. in late 2004 was that our presidential campaign coverage that year had been so lackluster—in content, presentation, and ratings. I cancelled our three main political programs—Crossfire, The Capitol Gang, and Inside Politics—almost immediately, without a firm plan for what we’d replace it with, because had I simply told our Washington producers that we needed to do things differently they would have nodded and then done nothing. We needed to create a gaping hole in the schedule—because institutions understand filling holes better than they understand evolving. Riding the subway back to the startup I was running following my first job interview at CNN, as I began to think about what the network could do to climb out of its woes, I wrote down two words on a notepad: “Situation Room.” Because CNN is a big brand that can make bold promises to the audience, and deliver on them—the same thinking that went into flooding the zone in our field reporting. So we really could be the world’s Situation Room—it’s what the world expects of CNN, actually. Then and now.

Stepping up and being the thing your customer wants you to be—is rooting for you to be—is usually a good business practice. So when I took the job and blew up those political shows, I handed those two words to our Washington bureau chief, David Bohrman, who I had known to be a creative force from our days both running Internet startups. I said “go figure out what a CNN Situation Room could look like.” To his credit, and that of his deputy, Sam Feist, who is now CNN’s Washington bureau chief, they took the ball and ran with it. They created a high-energy, tech-fluent, two-hour daily nexus of everything worth knowing about around the world that became the talk of TV news and best of all it galvanized our overall political coverage, leading us to win the Emmy for coverage of the 2006 midterm elections and go on to top all the cable and broadcast networks in our 2008 presidential coverage, which CNN had never done before or since. That surge of creative energy led to the introduction of John King’s Magic Wall at this time, and a joint presidential debate with YouTube that allowed ordinary citizens to ask questions of the candidates for the first time, and launched the first-ever Facebook livestreams. It turned out that the moribund coverage of 2004 was not due to lack of talent—it was due to the immensely talented CNN political team not having been asked to be as great as they could be. It was the same exact group who so dominated political coverage as soon as they were given the challenge.

The cancellation of Larry King’s show was due simply to plummeting ratings, which was not Larry’s fault at all. I think the network just evolved beyond that show, which had been on for twenty-plus years—we had come to be symbolized by the dynamism of Anderson Cooper, and Larry’s show—despite some extremely creative new approaches adopted by their production team—no longer fit. It was tough to say goodbye to a legend and a good guy with a phenomenal staff, who had been the mainstay of the network for so long.

BL: In 2005, you promoted Anderson Cooper to a prime anchor slot. He remains at CNN fifteen years later, and his talents have grown tremendously over this time. There are anchors on cable news who maintain some of the traditional approach and emotional empathy of past greats such as Walter Cronkite, David Brinkley, and Peter Jennings. Brian Williams and Willie Geist stand out on MSNBC and on CNN Wolf Blitzer, Cooper, John Berman, Poppy Harlow, and John King. Brianna Kielar conducts no-nonsense interviews and Don Lemon and Chris Cuomo are major talents. Is the anchor “personality” of 2020 partially a result of your decision to elevate and stick with Cooper? How do you feel about the pool of on-camera talent at this time?

JK: Television news has always revolved around commanding personalities who are able to present their authentic selves on camera. I’ve been fortunate to work with some of the all-time greats—including Mike Wallace, Dan Rather, Ed Bradley, Diane Sawyer, and Meredith Vieira—and one thing they all have in common is that they are not that different off camera from who you see on air. I was the executive in charge of 60 Minutes for a few years, and when I asked Don Hewitt, the genius creator and executive producer of that show (he made all the brilliant editorial decisions; my main function was to approve his expense reports and screen the pieces before they went on the air as a final editorial/legal backstop. In that order [sic]) why the show was so visually…vanilla…with no flashy graphics or zippy video, he told me something I’ve never forgotten: “Kid,” he said (I was 36, he was 75), “television is not a visual medium. It’s a means of connecting one human to another.” The best personalities in television news are able to connect. On top of that, journalists like Anderson and Poppy Harlow are phenomenal reporters, able to find things out because they know what to ask and they get people to answer.

BL: On November 1, Ben Smith of The New York Times wrote, “It’s the End of an Era for the Media, No Matter Who Wins the Election.” The national obsession with Donald Trump created new and financially lucrative opportunities for old media. Evelyn Douek, a lecturer at Harvard Law School, said, “we’re in this brave new world of content moderation that’s outside the take-down/leave-up false binary.” As industry executives leave their posts and other “players” jockey for position, there’s a kind of “Wild West” aspect to the news business, with outrageous content, misinformation on social media platforms, and name-calling from all sides. Where do you fit into this scenario?

JK: I’m a news consumer, not creator, now, but the startups I’ve been running since leaving CNN have given me hope that technology—which created the silos that people are now burrowed into deeper than ever—can help lead us out of them as well by highlighting what unites us as much as what divides us. I founded a streaming video platform called TAPP Media, that builds sites that connect super-fans to their idols. And it has surprised me to see how unpredictable people can be, how resistant to pigeon-holing. Our biggest video channel is Bishop’s Village, featuring T.D. Jakes, who runs the second-largest mega-church behind Joel Osteen. Can you guess what the most popular subject is for the subscribers to his channel? It’s divorce. I don’t know why—it just is. Now, I suspect that divorce/troubled marriage is pretty high on the list of subscribers to all kinds of digital media sites that have zero to do with religion. That’s a potential bridge.

In addition to TAPP, I ran an artificial intelligence company for media that recently sold to Apple, and AI has the ability to identify very granular attributes of consumers by analyzing their language, searches, viewing behavior, and more—and to do so while respecting privacy, if the humans behind it are committed to that goal. What I suspect we’ll start to see is that, although we may disagree strongly about the means to our collective ends, we probably share a desire for many of the same outcomes—good health, equal opportunities to improve our lives and those of our children, peace, and more. Media has a tendency to accentuate differences and conflict, because unity doesn’t seem “new” and newness is kind of baked into the word “news.” But I think there’s a path out of that conventional wisdom, if we choose to follow it.

BL: During boardroom tension and staff turmoil at CNN, did you have to sublimate some of the brighter aspects of your personality to get the job done?

JK: The only way to survive a high-stakes environment is to have a sense of humor about it and yourself. Although the head of HR at CNN did once tell me after a weekly staff meeting, “I notice you make a lot of jokes in there.” “Thanks,” I replied, “I’m glad you appreciate that.” “Well actually,” he said with furrowed brow, “I bring it up because a lot of times people make jokes to avoid the real underlying issue.” He was a smart guy, with a Ph.D. in organizational behavior, so I didn’t doubt him, and I tried from then on to make sure I wasn’t sidestepping necessary conversations through humor. But in the end, I mean, come on—it’s only TV.

BL: You’re are on the board of Unite, described on its website as “a growing collaborative led by Tim Shriver [a philanthropist, educator, and Chairman of Special Olympics International] and other Americans from all walks of life, dedicated to addressing universal challenges that can only be solved together.” Unite was founded because there has been a “great loss of faith in the American experiment, and each other,” which has been building for decades. The organization hopes to pull Americans back to reconnect “to what we have in common.” What made you get involved with the group and what do you think it can accomplish?

JK: I’ve known Tim and the entire Shriver family for over thirty years, ever since I produced the CBS Morning News with his sister Maria as anchor. He is one of the most dynamic and inspiring people you’ll ever meet—JFK-like in his mix of intelligence, vision, articulateness, and charisma. I became involved because Tim’s vision of pulling together across geographic, political, ethnic, and religious divides is so critically needed right now, and his determination to make it real so powerful, that I couldn’t resist. The Shrivers have a way of being able to turn pure intentions into reality—whether it’s the Special Olympics founded by Tim’s mother, Eunice; the Peace Corps, Job Corps, Head Start, Meals on Wheels, or VISTA founded by his father, Sarge; or Best Buddies, created by his brother Anthony—and it’s a thrill to be able to help Tim bring Unite to fruition at this urgent time.

As for what we can accomplish—we’re trying to change the narrative of America, to present the nation we believe is out there behind the labels too often affixed by [the] media. As a journalist, I’ve met people at the most extreme moments of loss, fear, anger, and need, as well as those trying to help them—and you know, a firefighter racing to save a family’s home, or a cop trying to find a missing child, or a doctor working to save a struggling newborn baby never ask “who did you vote for?” And I never asked them that question either. That suggests that we share something deeper as human beings and Americans. Unite is focused on illuminating that shared purpose, and encouraging a different kind of discourse. I think there’s a hunger for that out there.