An Interview with Artist Ann Chernow of Westport, Connecticut

Bernie Langs

The artist Ann Chernow was born in 1936 and grew up in New York City. She has worked extensively in the mediums of lithography, silkscreen, etching, and colored pencil as well as oil painting. Known as “The Queen of Noir,” she achieved extensive recognition for her portrait-style works evoking the images of female cinematic figures from the 1930s and 1940s, especially those appearing in black and white films. Ms. Chernow has lived in Westport, Connecticut for many years, where she is a long-time and beloved leader of the extended arts community.

Chernow’s second husband, Burt Chernow (d. 1997), was an art historian and professor at Housatonic Community College, where he founded the Housatonic Museum of Art. The couple established a wonderful art collection, including prints and works in various mediums by some of the greatest artists of the twentieth century. She later became the life partner of actor and documentarian, Martin West (d. 2020). Chernow has traveled the globe and befriended numerous artists and art dealers.

When you view Chernow’s works in person, you can’t help but be struck by her use of representation and portraiture as a means of evoking a sense of veiled mystery. Chernow’s work elicits a tactile response to the many textures of her graphic details. Her works grab the beholder with immediacy and profound emotion.

In late August 2020, Chernow was kind enough to respond to interview questions by email:

You are in your 80s and you’ve said that with so many ideas for new works, you’ve considered putting together an Andy Warhol-like “Factory” of assistants to speed up the process of making prints, etc. Is it both a blessing and a curse that after decades you are as creative, if not more, as ever?

There are many artists who have assistants actually creating the artist’s work. I have had years of studio help but never had people making my work though I’ve considered it because I’ve never been able to bring to life all the images crowding and dancing in my mind. I usually fall asleep mind-creating images. If I could live hundreds of years, I could never realize all of them. Choosing the images I actually produce is akin to choosing what children you would keep. I’ve come to an acceptance that I can only do so much. But I decided long ago never to have other people making my work.

I have many non-artist friends who are retired but I’ve never thought about retiring. One of my mentors, the artist Isabel Bishop worked every day. Even in her late years with Parkinson’s as her devil, she took a subway when she was able to from the Bronx to her studio in Union Square in Manhattan. She, and others like her, are my heroes. It’s neither a blessing nor a curse that the images just keep coming, it’s just work; it’s my life.

I consider you one of the few remaining creatively original and great representational artists. What motivates your reality-based work?

During the past fifteen years most of my work has been informed by the movie genre of film noir. The images are based on specific impressions related to movies from the 1930s and 1940s then freely interpreted without altering the spirit of the chosen cinematic information. I try to create a sense of déjà vu or nostalgia without the sentimentality often associated with specific film references…I alter the perception of “star” using contemporary models; this attitude brings an image closer to the contemporary viewer. Depicting a universal gesture and establishing dramatic moments are paramount. Once experienced, a movie is never totally forgotten. Memories from films are channels, metaphor and private reverie through which I address the human condition. I’ve never followed “trends”.

Serious work began in college, NYU’s art programs offered new insights. It was the 1960s and Abstract Expressionism was the style of choice. I was asked to leave a number of classes because I refused to work abstractly. The artist Jules Olitski was the only instructor who understood what I was trying to reach, and even though he was an Abstract Expressionist, he allowed me to work realistically, telling visual stories. I’ve never deviated from that approach.

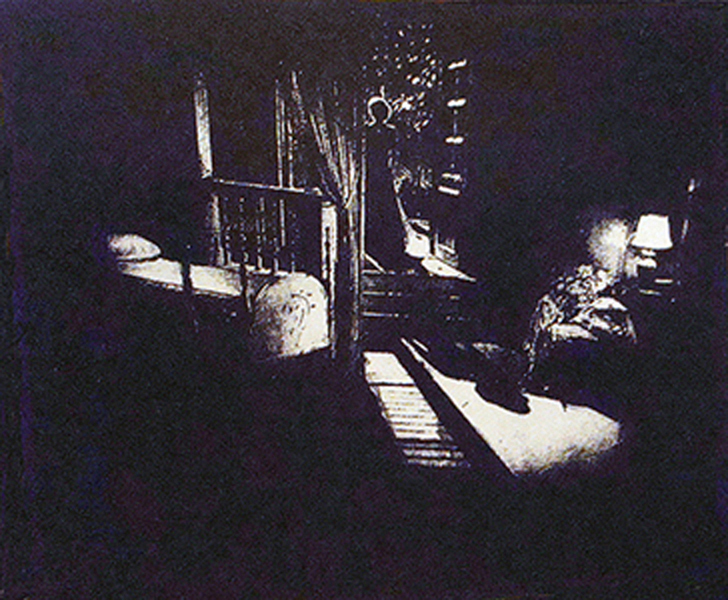

Your Shadow of a Doubt series evokes an amazing response when experienced in person. How did you conceive of the series?

Shadow of a Doubt uses images culled from the film noir, Laura, which is one of my favorite films. I’ve watched it many, many times, sketch from it, then push the aesthetic to reach a satisfying composition with many levels of the colors black to white. The various media I used: lithography ink, pencils, sandpaper, razor blades, and “white out’ (yes, it’s the liquid that erases mistakes on paper, but it also works on other surfaces). I use this media combination with paintings, drawings, and prints. I usually concentrate on images of femmes fatales and Gene Tierney as Laura is [a] quintessential [femme fatales].

From late March to May of 2020, the Center for Contemporary Printmaking in Norwalk, CT had an exhibition, “Collaboration 2020: Ann Chernow and James Reed Explore the Lithographs of Pablo Picasso” where you researched Picasso’s techniques extensively and created a set of prints using what you had learned. How did the project and exhibition come about?

My master printer, James Reed, and I had the idea five years ago to try to replicate the surface feeling of a Picasso print. We researched and soon realized that even the most detailed catalogs did not include specific information on the methods or actual material processes used by Picasso. Further research and speaking with experts revealed that no printer could supply that information. So, James and I set out to use an image of mine to achieve this [texture]; we tried many experiments with various materials. When we finally successfully completed one print, we were so excited that over the next five years—between other print work—we realized sixty-one Picasso/Chernow works, most of which were experiments with media.

You were close friends with the artist Christo, who recently died, and his late wife and collaborator, Jeanne Claude. Your late husband, Burt Chernow, wrote a biography of the couple and your late companion, Martin West, was also deeply involved with their monumental projects. What can you say about having been so close to Christo and his influence?

My heroes are those whose work ethic dominated their lives. Christo and Jeanne Claude lived their work, not much else interested them. Once, their lawyer persuaded them they needed to take a vacation; after two days they came home, bored with doing nothing. That work ethic is what I most admired, along with the wonderful absurdity of their realized projects. We worked on every one from 1971 until the Central Park Gates. Before he wrote the biography of the Christos, Burt and I spent three weeks in Bulgaria, where Christo was born and lived until 1968 when he fled that country for France. It was one of the most interesting trips of our lives. Burt died before The Gates was realized. Martin West and I took open “rickshaws” around The Gates, and he [Martin] filmed them. All our lives were enriched by the years with the Christos.

My novella, The Empathiad, has your Lady in the Lake on the cover; seeing it changed the direction of the book after I discovered it online. Do you consciously aim to be inspirational and mysteriously obscure to your viewers and other artists?

Lady in the Lake embodies the raison d’etre for my work: it’s a reinterpretation from a film noir [film]. It’s a subject that’s universal, open to the viewer’s interpretation; what the femme fatale is doing is open to the imagination, it’s dramatic, it could be a placid moment or dangerous, but it’s accessible. To quote from Alice Munro, “You just have to have the will to disturb.”

How would you describe the magic of Westport as a haven for artists?

Westport, Connecticut, has, since the early 1900s, been known nationally as a haven for visual artists, writers, theatre people, musicians, art collectors, entrepreneurs, and teachers. One of the first artists to arrive here in the early 1900s was Arthur Dove, whose work here changed the face of American art. It happened like the Pied Piper: artists would move here, for the summer or for the year, their artist friends would visit and then follow. Martin West, my life-partner and documentarian, addressed this in his 2000 film A Gathering of Glory, which covers all the arts. In 2009 he created another film, [Years in the Making] about fifty Westport artists over the age of 70 who were still actively working in their studios and having national exhibitions. It won seven awards in national film competitions, had a red carpet opening at the local cinema in 2010, and was shown on national television. Martin was developing a documentary about my work, called A Moment in Time. A filmmaker friend hopes to complete it next year.

Martin West was an extraordinarily kind and generous man. What else can you tell us about him?

Martin began his acting career in New York City in the play, The Andersonville Trial. He was 22 when he made Freckles, his first movie in Hollywood. [He also appeared in the last film made by the legendary Alfred Hitchcock, Family Plot]. Before leaving Hollywood and moving here [Westport] in 1993 to open a filmmaking business, Martin starred in over thirty movies, [spent] nine years as a soap opera star as General Hospital’s Dr. Brewer, and [appeared] on numerous TV shows including Perry Mason, Gunsmoke, Law and Order, and Bonanza among others. He was an extraordinarily wonderful person, smart, funny, empathetic, interesting, kind, and every other positive adjective to describe a special person.

You’ve had a difficult past year with the loss of Martin and Christo, being confined by the pandemic, and living without power for days after a recent hurricane. What lies ahead of you as an artist and with your commitment to the Westport artistic scene?

Yes, this has been a daunting year so far with both human and natural disasters. Work is my salvation. I have just completed ten lithographs for a portfolio titled, Femmes Fatales. I’m also illustrating a group of poems written in noir style by a friend about the seven deadly sins. I’m co-author of a monthly column: “ART TOWN” in The Westport News. I’ve been made an honorary member of the Westport Collective, a group of about 150 artists from in and around Westport. I continue to work with the Westport Public Art Collections, and the Housatonic Museum and Norwalk Community Art Collections. I write short stories when I’m too tired to make art [and] have had one published, which won an award. Towering above all of this, I have a caring family who has kept me sane through all of the major difficulties of the past year. I have always been a “glass half full” person and hope to continue working for a long number of years.