A War of the Worlds for the Age of Pandemic

Bernie Langs

Spoilers below!

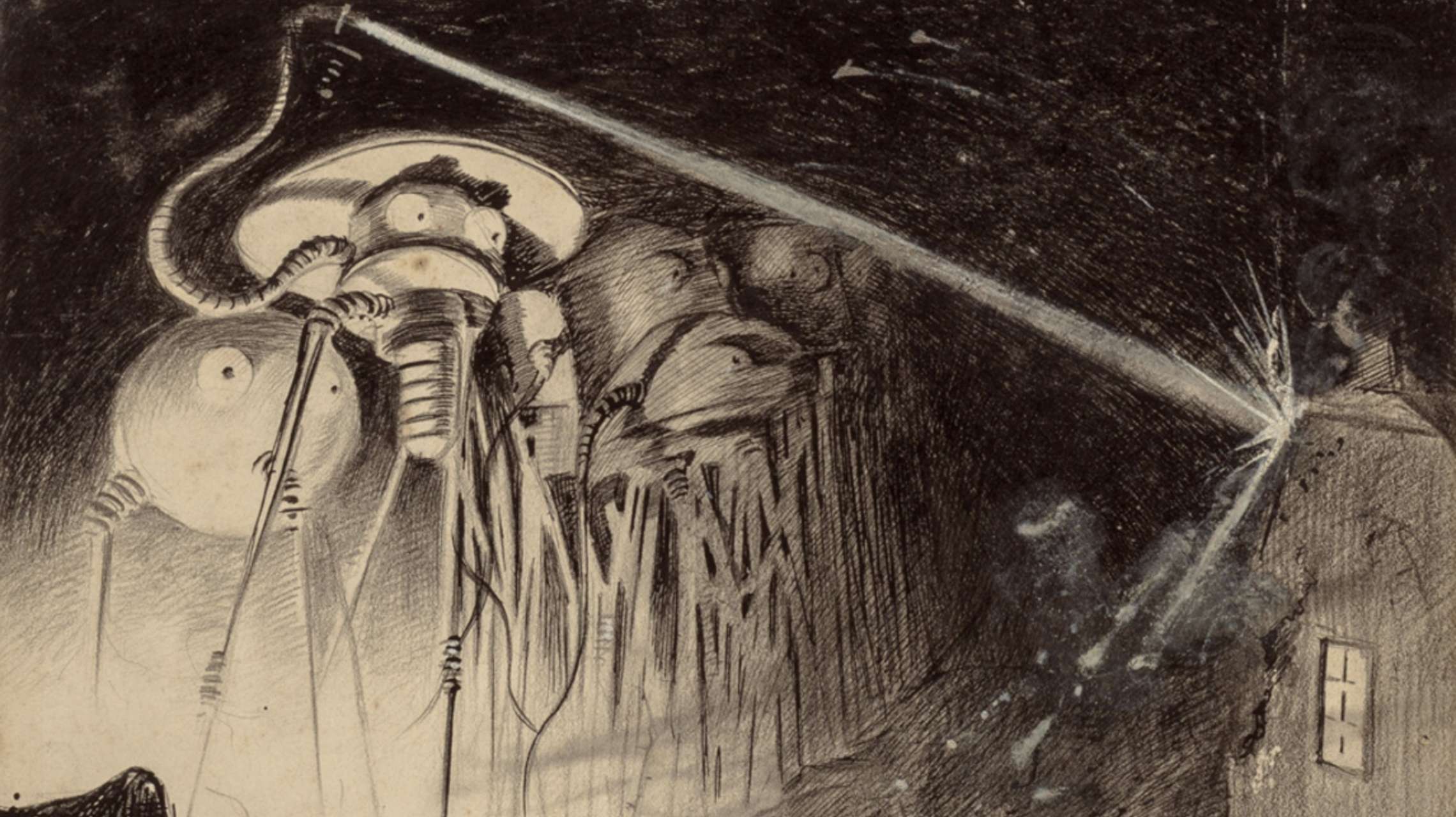

There have been two excellent film adaptations of the ahead of its time 1898 science fiction novel by H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds. Gene Barry starred in the 1953 movie that would find repeated airtime in the late 1960s on local New York television, where I first viewed it as a boy. The most memorable moment (and sole remembrance for me) is towards the end of the story, when the terrified humans not yet slaughtered by the invading armies of aliens, take refuge in a bombed church. In 2005, Steven Spielberg directed a fantastic take on the notion of a merciless killing machine of invaders, with Tom Cruise as the hero (Ray Ferrier) who is forced to take fast and imaginative action to survive. The movie focuses on Ferrier’s desperate attempt to stay ahead of the alien starships as they pillage and destroy not only human life but turn the very earth itself into a blood-soaked wasteland. Spielberg effectively transforms Cruise’s character of a divorced and out-of-touch father of a young girl (the superlative Dakota Fanning) and teenage son (well-played by Justin Chatwin) into a selfless defender willing to take all measures to protect his family. In the last scene, as the aliens are dying off and crashing their vessels into sections of Boston, a tongue-in-cheek surprise occurs when Ferrier reaches his ex-wife’s home to safely deliver his daughter. He is greeted not only by his ex-wife and their son (who had been thought dead due to an earlier attack), but also by his former father-in-law, portrayed by none other than the star of the 1953 War of the Worlds, Gene Barry.

In both movies, the aliens easily repel the greatest efforts of mankind’s weaponry, only to die off naturally soon after their invasion.They succumb to the worlds’ ecosystem and atmosphere and are unable to defend themselves from microbes and bacterial disease. Although they are technologically superior and advanced, these monsters still die from invisible and natural attackers. The dread and fear that Spielberg evokes not only comes from the monstrous appearance of those steering the alien forces, but from the sounds their ships make announcing their approach. In one touching sequence, Cruise and his children march silently through a town with hundreds of other weary, fatigued, and fleeing refugees. The village’s walls are plastered with missing person posters, very much like those that covered Manhattan in the days after the September 11th attack. As the 1953 version of War of the Worlds might be considered a study in Cold War angst, the Spielberg film is a bleak portrayal made for the post-9/11 era. Harking back to the radio play voiced by Orson Welles in 1938, one can sense that it too was a mirror and reflection of the times. It would be but a matter of months before much of Europe would lie in ruin from the German onslaught of World War II.

Science fiction movies of aliens wreaking havoc on the earth come in several brands, the most popular being those depicting them as harsh killers desiring earth’s minerals and vegetation, as well as human flesh for sustenance. A few recent movies turned the genre on its head, including the remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still, where destruction is targeted only at the human species by a superior race of invaders who intend to save all other natural life forms from pollution and destructive wars. The 2016 movie Arrival is quite sophisticated and smart, as the army and intelligence units enlist a brilliant linguistic professor (Amy Adams) and physicist (Jeremey Renner) to break through in communicating with enormous octopus-like aliens manning ships hovering over major cities with unknown intentions. Arrival dives deep into science and philosophy and boasts a breathlessly tense and intellectually satisfying resolution.

A new eight part Epix series based on H.G. Wells’ story debuted in the U.S. in early 2020. This version of War of the Worlds draws from the best approaches of past renditions and other alien invasion stories and makes a timely contribution to the surreal and challenging times we currently inhabit. Aired just prior to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, its lessons would have been equally as powerful had it been released two years after the end of this crisis.

Unlike the unfolding days and weeks of murders of past War of the World films, most of the mass killing by the invaders occurs immediately in this series. The handful of survivors living in England and France are initially saved only by finding accidental shelter from the destructive sound waves that killed millions of their fellow humans in a flash. The aliens are on a mission to not only hunt down and kill these survivors one-by-one, but also harvest their organs. In early episodes, we are teased with fleeting views of the aliens, making us think they will be as terrifying as those that Spielberg set loose over fifteen years ago. But the galloping dog-like creatures turn out only to be crude, metallic, robot-like machines (plenty scary though when they kill people). When one of them is finally destroyed and split open, it appears to utilize inexpertly cobbled together human tissues for its rudimentary thinking and actions. It becomes apparent to the survivors that these are only worker drones or soldiers of an unseen master (or masters) who have yet to reveal themselves from the mother ships.

Family and survival are a key to this series, but in a 21st century way that Steven Spielberg could never have anticipated in 2005. One English family, the Greshams, consists of a matriarch, Sarah (Natasha Little) and her two teenage children, the quietly pensive, but thoughtful Tom (Ty Tennant) and blind daughter, Emily (Daisy Edgar-Jones). The viewer is teased into believing that Sarah will act in the Cruise-like role of steadfast family protector, but immediately her children question her protectiveness as selfish when they are confronted by people in need whom their mother wants to bypass and leave to fend for themselves. This dynamic becomes more and more complex as the series evolves. On the French side, the Dumont family unfolds as a portrait of modern dysfunction to a tragic degree. Even in a time of emergency, the force and power of their past failures and pains cannot be escaped and become a danger to themselves and to the one man, Jonathan, trying to save them. He also happens to be the head of the Gresham clan and his goal is to return by foot via a long trek to London through The Channel Tunnel, where he hopes to reunite with his wife and children, should they still be alive (the viewer knows they are, but he doesn’t).

The most interesting aspects of this War of the Worlds are its portrayal of the two scientists, Catherine Durand (Léa Drucker), an astronomer in the Alps who first hears the signal of the invading force on a frequency in an observatory, and Bill Ward (Gabriel Byrne), a brilliant and aged neuroscientist in London. Unknown to each other, as both face life-and-death situations with their one surviving family member, they are attempting to figure out a method to defeat the invaders based on their own training. Ward wants not only to discover the aliens’ vulnerabilities, but to learn and comprehend its motives. It is this plot device that makes the production so unique. The unknown entities ruthlessly attacking are not here to blindly destroy or colonize or save other species from humans. What they crave is life itself—their own lives—and their fear of death, quite a human notion, is what motivates their blind pursuit of any actions that may save their species from oblivion.

The series has countless shots of the streets of London and towns of France eerily empty at the height of the day, quite like what we are witnessing during our virus-protective lockdown in April 2020. Never has a television film centered on destruction been so eerily silent for so many long sections of its telling. Durand in France tunes into the alien signal at one point to hear music playing. It turns out to be one of the songs that astronomers launched in a space vehicle hoping to discover other intelligent life forms in the galaxy, quite like what NASA has done in the past. To her horror, Durand realizes the song she hears is one that she so harmlessly selected for the probe herself. The invaders found earth by tracing back the music to its origin and the astronomer is devastated to learn that it was her team’s recordings that led them here. In the final episode, Durand does find a frequency to disable the attack – at least for now, but we are not witnesses to its implementation. However, there are other complex and very gray aspects to the final episode of part one of the series that make for great emotional and tragic drama.

I was taught long ago in school that bacteria, the killers of aliens in past War of the Worlds films, were living, natural beings. Viruses, on the other hand, I recall as a membraned “box” encasing a squiggly line of nucleic material with a small antenna-like shape atop—a killing machine knowing nothing but sucking life-force from its host and replicating like a blind monster. In the Epix series, the aliens adapt their destructive plans as humans make headway in understanding their weaknesses. Similarly, a virus mutates to evade medical treatments. Yet with great effort, scientists eventually discover medicines that viruses ultimately succumb to no matter how they morph. It may be a little silly to say that life will be true to art here, but in my heart, I believe that it will be our tireless, selfless scientists who bring down or find a way to protect us from this current viral invasion.