Bernie Langs

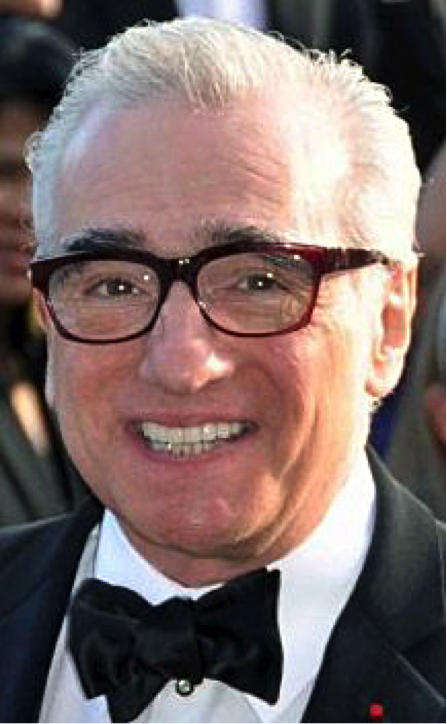

Martin Scorsese and Silence

Martin Scorsese, who I consider America’s greatest living film director, is a creative talent with the ability to continuously surprise his audiences in terms of what he chooses for his huge enterprises. Yet, the quality of the final story on the screen may vary. With that said, I find some of his movies absolutely brilliant, from their rich palettes of cinematography, to the impassioned and inspired performances of the actors and actresses, and the stimulating ideas that always aren’t black and white in these tales of extreme moral and ethical quandaries. My personal favorites from the Scorsese oeuvre include Raging Bull, The Departed, Good Fellas, and The Aviator.

From his early days of films such as Mean Streets and later (more blatantly) in The Last Temptation of Christ, it became apparent that the Italian-American Scorsese was struggling to come to terms with his Catholic upbringing and the meaning behind the story and lessons from the life of Jesus Christ. In the final scene of Raging Bull starring Robert DeNiro in a beautifully nuanced performance as troubled boxer Jake LoMotta, the screen displays these words from the New Testament (John IX. 24-26): “So, for the second time, [the Pharisees] summoned the man who had been blind and said: ‘Speak the truth before God. We know this fellow is a sinner.’ ‘Whether or not he is a sinner, I do not know.’ the man replied. ‘All I know is this: once I was blind and now I can see.‘” The idea of being clothed in the darkness of ignorance and having the light shine in on life, courtesy of a Savior, is powerful.

Scorsese’s 2016 film Silence is right up there as one of his very best. It is a movie about not just Catholicism because it also examines the boundaries, trials and tribulations, and other tumultuous ethical situations surrounding the ideal of staying true to one’s own morality and choices, not only in God’s eyes. It is a long movie and didn’t fare well at the box office, but I was absolutely riveted from start to finish and overwhelmed by the force of the ideas on display.

Silence stars Andrew Garfield as Sebastião Rodrigues and Adam Driver as Francisco Garupe as a pair of young 17th century Jesuit priests traveling from Portugal to Japan to locate their former teacher (played by Liam Neeson), who had gone to Japan to teach and convert the populace to the ways of Catholicism and goes missing after supposedly renouncing his faith.

When Fathers Sebastião and Garupe reach Japan, they are taken in and hidden by the terrified villagers who are converts to Christianity at a time where the religion is being violently suppressed and must be practiced in secret. While watching Silence, I was awed by the beautiful, lush scenery of the mountains and foliage depicted. The stunning scenery becomes the backdrop of the violence that reigns down from the minions of a horrific inquisitor on these people. The inquisitor is masterfully played by Japanese actor and comedian, Issey Ogata, who the New York Times noted as stealing ever scene he is in.

As one watches the struggles of Sebastião unfold, dozens of questions and ideas run through the mind of the viewer on issues that center around the crux and core of faith in God, but also Western ideas forced onto Eastern cultures, and on the difficult notion of whether one should betray ones greatest beliefs for the greater good. The focus centers on the dilemma facing Sebastião when he is given the choice of renouncing Catholicism or seeing villagers tortured to death. All of the intellectual banter of the inquisitor and his interpreter, the latter beautifully portrayed by Tadanobu Asano, devolves into their extreme meeting out of violence on the bodies and minds of the poor villagers, who they deride as worthless peasants. By breaking Sebastião, they can publicly break a man who has devoted his heart, life and soul to what they believe is the affliction invading Japan.

Before Sebastião does his act of apostasy, the inquisitor brings in the man Sebastião has come to find, Father Cristóvão Ferreira, played by Neeson. He arrives late in the movie like Marlon Brando’s Kurtz does in the film Apocalypse Now. As he begs his former pupil to renounce his religion in the hope of saving lives, he makes one extremely powerful argument: that these poor, uneducated Japanese men and women, the derided so-called peasants, aren’t truly practicing Christianity because of their prior beliefs and ingrained culture and simple notions of spirits. He’s basically saying, “It’s all for nothing.”

Silence is a reminder that barbarity, such as that practiced by ISIS today, the torturing and murder in the name of God and religion goes back to the dawn of man’s conceptualization and organization into religious sects. The inquisitor, a witty, well-read man of knowledge, can banter with Sebastião on ideals and ethics one moment, while ordering the decapitation of a prisoner in a courtyard for all to see the next. Scorsese has a long history of using extraordinary violence in the hopes of finding some inkling of why God has put us on earth in the first place, and to seek an idea of how to live one’s life in the face of brutality and terrible suffering. But he never openly actually says, “Jesus is the answer.”

From the interviews I’ve read with Scorsese about Silence and from what I’ve learned from reading about him in the past, he is more a man who is opening up ideas about searching for rather than explaining the meaning of life. He often sounds quietly and admittedly lost, but very glad to have the opportunity to make art and films about his state of confusion.

It has become my opinion that because most people are taught about faith and religion in childhood, it is incredibly hard to shed any of the major faiths later in life. It’s akin to an indoctrination. As I’ve grown older, I’ve read many of the books from the past by religious luminaries, such as Rashi’s commentaries or Jerome’s letters and books by Augustine and Philo; the texts of ancient Buddhists or the ideas behind the spirit religions of Japan; the fascinating words of the “Upanishads” and the “Bhagavad Gita” and the creation stories as presented in Assyrian myths or related by Hesiod to the Greeks, and many other illuminating treatise. I believe at some point one must start anew with a clean slate and admit that the spiritual notion behind the concept of God is as complex as advanced physics and that a child’s idea of what lies behind the abstraction, hinted at in the Old Testament, that a casual once-a-week (at most) rote Sabbath notion has as much truth and merit as an adult belief in say, Santa Claus. Imagine that the power and forces of life or what is popularly called “the divine” is encased inside of a statue of a golden calf and that all of the major faiths and religions are blind and given only one part to feel with their hands and gather its meaning. Each religion falsely and confidently believes they know the full statue and its secrets, while in truth, the one with the dominant voice in society may very well have its hands on the rump. None of the followers of any religion knows or realizes that the power lies hidden inside the idol and that the statue has very little to do with the immense power of this vaguely traceable treasure. Why settle for one set of rules and rituals when there is such a rich tapestry available for study, which weaves together everything from philosophy to astronomy and on and on, endlessly woven, ripe for discovery and continued revelation? (Unified Field Theory indeed). What is really so terrible that we end up like Martin Scorsese in some way: in awe of the unanswerable, and finding ways to express our intuitions and discoveries in art, music, books, and science? Because in the end, whether it is Judaism, Christianity, Islam or the religions of the East, the zealots of each faith make them all superstitious faiths borne of unspeakable and unjustifiable violence while serving as Band-Aids to the open wound of awareness of one’s own mortality.