The Rockefeller University has a singular mission: to “do good science.” This statement, given by President Richard Lifton at an annual meeting with the Student Representatives Committee (SRC) on May 8, 2024, seems, at first glance, to be an innocuous paraphrase of the Rockefeller University mission statement. If you parse it further, however, it reveals a shallow understanding of the context in which science is done and the role of scientists therein.

Prior to this meeting, the SRC had received multiple requests to ask the Office of the President why the University has prevented students from hosting political and religious events on campus, such as a vigil for victims of the Israel-Hamas war and a Palestine Benefit Iftar during Ramadan. According to minutes distributed by the SRC, Lifton replied that, while “undergraduate universities are broad and have many missions, including being a place for people to debate a wide range of topics,” Rockefeller’s sole mission is to “do good science.” It is not the University’s responsibility to be a “forum for political debate,” he added, citing that there are “plenty of opportunities to do that elsewhere.” One such place might be just across the street, as Cornell University recently announced a Task Force on Institutional Voice to discuss how to address matters of politics, ideology, current affairs, and world events.

Executive Vice President Timothy O’Connor, also present at the meeting, then ended the discussion by offering to send SRC members the University’s Code of Conduct and its Policy on Use of University Facilities, which “prohibits the use of University Facilities for events with a partisan political, religious or fundraising purpose.” (In a town hall on January 28, 2025, Dean of Graduate and Postgraduate Studies Tim Stearns clarified that the Faculty and Students Club and the Scholars Residence Solarium can be used for any kind of event, including political and religious ones.)

President Lifton’s comments make up part of the longstanding debate about whether science is political. He argues that The Rockefeller University, as an institution where scientists do science, is an inappropriate venue for political expression and debate. Before addressing Lifton’s claim, it will be helpful to establish working definitions for both “science” and “politics.” Drawing from the proverbial high school science textbook, science can be defined as the process of acquiring knowledge through the scientific method, namely, the cyclical process of devising questions, forming hypotheses, conducting experiments, and analyzing results.

While the “political debate” Lifton mentions evokes the frustration of presidential debates and the tohu-bohu of congressional hearings, electoral politics and government functions constitute a rather narrow definition for something as complex as politics. More broadly, politics can be understood as the decision-making processes within a group of people and the power relations that affect those processes. That both political and religious events are prohibited on campus raises an interesting comparison between the two. Just as the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution legally mandates the separation of Church and State but has failed to prevent politicians from imposing their religious beliefs on the general populace, the claims of people like Lifton that science and politics should be separate do little to realize this division. Regardless of its basis in reality, the idea of science as apolitical has carried significant weight among scientists for some time.

When Did Science Become Apolitical?

The same proverbial science textbook that teaches the scientific method also traces the roots of modern science to Western Europe, sometime between the 16th and 18th centuries. The protagonists of the scientific revolution—characters like Galileo Galilei, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton—are often seen as the drivers of an intellectual shift away from religious or classical philosophical notions of the world and towards an enlightened understanding of nature. This, as historian of science and technology James Poskett argues in his book Horizons: A Global History of Science, is a “convenient fiction” that erases global contributions to science across a larger time frame. In fact, as Poskett explains, many of the advancements of the scientific revolution drew from Arabic and Persian mathematical texts, Chinese and Indian astronomical observations, and Islamic and Jewish science developed centuries earlier. Even today, it is the global cultural exchange that makes scientific innovation possible. Poskett writes that this fiction began to be propagated during the Cold War by U.S. and British historians. However, it was not a product of ignorance, but rather a calculated attempt to deify a handful of European geniuses and frame their compatriots as the “bearers of scientific and technological progress,” in contrast to their ideological adversaries in the East and Global South.

The Cold War saw not only a revision of the history of science but also the ideological purification of science as a discipline. In 1928, the Soviet agronomist Trofim Lysenko began to argue in favor of Lamarckian inheritance and against Mendelian genetics and natural selection, since the former squared better with the political ideology espoused by the Soviet Union. His flawed theories were adopted as the official Soviet understanding of biology, and detractors were fired, imprisoned, or executed. In her 2020 book Freedom’s Laboratory: The Cold War Struggle for the Soul of Science, historian and sociologist of science Audra J. Wolfe chronicles the U.S. response to this politicization of science. While communist science was said to mandate adherence to party dogma and reward political loyalty and nationalism, U.S. propagandists used the political rhetoric of freedom to “create a vision of science in the United States that highlighted empiricism, objectivity, a commitment to pure research, and internationalism.” Allegedly free from government control, science was now apolitical.

This apolitical science, the bedrock of most scientific research institutions in the U.S. today, “had to be constructed and maintained through a series of political choices.”

Ironically, this perceived autonomy and credo of scientific freedom limited scientists’ ability to realize that their work was serving projects they neither controlled nor comprehended. The Central Intelligence Agency poured millions of dollars into various cover organizations that promoted U.S. scientific and cultural work by subsidizing scholarly publications, funding conferences, and translating biology textbooks. Scientists believed they were free to pursue their work without political interference, even as scientific research funding made up a greater portion of U.S. federal spending during the Cold War than in any other peacetime federal budget. This apolitical science, the bedrock of most scientific research institutions in the U.S. today, “had to be constructed and maintained through a series of political choices.” Its apoliticism is, consequently, yet another “convenient fiction.”

Not only has the fiction of apoliticism had considerable staying power, but it has also bolstered the myth—which existed long before the Cold War—of the scientist as a sort of intellectual ascetic who, unbound from the social and political drives of nonscientists, dedicates themself to the pursuit of knowledge. The apolitical scientist, however, is a character people are less likely to believe in than the concept of apolitical science. While some certainly see scientists as able to eschew bias, recent polemics—such as those on the use of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for SARS-CoV-2 or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s planned investigation into the debunked link between vaccines and autism—highlight a growing mistrust in scientists’ ability to remove themselves from politics.

Political Scientists, Apolitical Science

Perhaps, one might concede, scientists are biased and political creatures; science, however, is not. Though scientists are not some unbiased subspecies of human, they are still able to arrive at some sort of scientific truth through an iterative process of consensus-building and political and social interaction. As bioethicist Gregory E. Kaebnick and philosopher Bruno Latour separately explain, the scientific method essentially corrects for the biases of humans through its systems of peer review, reproducibility, and replicability. However, these are still human-mediated processes that continue to create room for error, rendering science less than the ideal of absolute truth. The collaborative, consensual decision-making inherent to science makes it, by definition, political. Science is not done by scientists in a vacuum, but rather in the institutions where they work. It is also beholden to various sources of funding, which are all governed through politics. Insisting that science is apolitical because of its protections against human bias does not make it less political; rather, it precludes a “better understanding [of] the political conditions that make science possible, the political choices involved in organizing and administering it, [and] the political ideologies and structures that threaten it.”

Beyond the Iron Gates

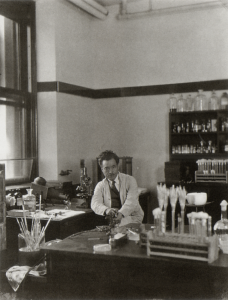

The sources of scientific funding can complicate notions of political influence in scientific research. This is no less true for The Rockefeller University. Dan Kiley, the landscape architect hired to design the campus in 1958, sought to “reinforce the idea of an urban oasis, […] as in ancient walled gardens founded upon the notion of paradise on earth.” Despite the architectural segregation of this “scientific village” from the “noisy and turbulent city,” as its Digital Commons describes it, The Rockefeller University has always been involved with the politics of the outside world. An unwitting example of this is the work of Japanese bacteriologist Hideyo Noguchi.

Although separate institutions, The Rockefeller Foundation, a private philanthropic organization founded in 1913 by Standard Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, Sr., was (and likely continues to be) closely linked to The Rockefeller University, founded in 1901 by the same Rockefeller. From its inception as The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (RIMR) until the late 1970s, all of the directors of the University simultaneously held positions on The Rockefeller Foundation’s board of trustees, as reported by Darwin Stapleton, Executive Director Emeritus of the Rockefeller Archive Center. In 1918, the Foundation recruited Noguchi, who directed a laboratory at the RIMR, to spearhead a series of expeditions in Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Brazil, and West Africa to investigate the microbial cause of yellow fever. In 1929, the year after Noguchi’s death, the Foundation established a virus research laboratory at the RIMR to continue the research on diseases like yellow fever.

Although marketed as a humanitarian or scientifically motivated effort, Foundation-funded research into contagious pathogens was undergirded by capitalist interests. As physician and public health specialist Saúl Franco Agudelo relates, The Rockefeller Foundation invested its epidemiological research in areas of economic interest like the rice regions of south-central Mexico and the oil-rich regions of Venezuela and Bolivia. In their book Social Medicine and the Coming Transformation, Howard Waitzkin and co-authors explain that infectious diseases “reduced workers’ energy and, therefore, their productivity,” making the regions where the diseases were spreading “unattractive for investors and managerial personnel” and increasing the cost of labor due to medical treatment. Much in the same way that medical treatment for African slaves in the antebellum South was viewed as an investment in human capital, Frederick T. Gates, an important advisor to the senior Rockefeller, encouraged his investment in preventive medical research “because health is found in a variety of ways to be profitable” (quoted in E. Richard Brown’s book Rockefeller Medicine Men).

There is little doubt about the dedication of researchers like Noguchi to their work in investigating the cause of yellow fever and other diseases. A 1928 obituary in The Lancet described him as someone who “loved science for its own sake.” However, even if researchers are not directly compelled to carry out their investigations for a particular reason, the underlying intentions of those who financially or politically support research call into question whether it can truly be science for its own sake.

The Role of Scientists

That science is political by nature is not a good or bad thing; the issues arise when science is viewed as an objective, detached source of knowledge immune to society’s imperfections. Contrary to what President Lifton argues, it is necessary for places where science is done to be “forum[s] for political debate.” The insistence that these institutions refrain from political engagement is rooted in the antiquated notion of science as a “pursuit of pure knowledge for its own sake.” Science is no longer the amateur pursuit of those with means; it is a professional career that people pursue, at least partly, because they need to earn money in order to live. Despite the cloudiness of titles like “fellow” or “associate,” graduate students and postdoctoral researchers at institutions like Rockefeller are workers who are there to produce value for their employers, whether it be the social capital of adding another name to the Prize Wall outside Caspary Auditorium or the financial capital of earning grants for further research. Scientist and historian John Desmond Bernal argues that these institutional interests exert a latent control, “if not in detail, then in the general direction of research.”

In this day and age, scientific research is a business investment. As the ecologist Richard Levins and the biologist Richard Lewontin note, “research expenditures are the first to be cut back when a corporation suffers economic reverses, presumably because technical innovation has no immediate payoff, while increased advertising, labor costs, and material costs can be immediately reflected in profit.” This emphasis on profit hampers the very creativity and innovation in scientific research that has made it such a valuable field. Scientists, like all workers, are not exempt from capitalism’s individualizing drive towards competition rather than supportive collaboration.

The underlying intentions of those who financially or politically support research call into question whether it can truly be science for its own sake.

This profit-driven mentality affects not only individual scientists but also scientific institutions as a whole. When publicly funded scientific research breakthroughs are consistently licensed out to the private sector, where they are subsequently developed into exorbitantly priced commodities, scientific agencies like the National Institutes of Health are seen by hostile government officials and advisors as abstract, inefficient bureaucracies undeserving of significant investment. Claiming that science is apolitical as the effects of its current politicization in Washington become increasingly tangible is an exercise in self-delusion. To ensure the longevity of the scientific enterprise, awareness is not enough—scientists have a responsibility to engage in political action and debate. The recent trend of unionization efforts among postdoctoral researchers and graduate students in U.S. research institutions, including the success of United Postdoctoral Researchers of Rockefeller-UAW and Weill Cornell Medicine Postdocs United-UAW, marks a renewed effort towards the self-determination of scientific workers and a political and grounded commitment to science.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., claimed in 1919 that the Institute’s research was “free of dogma, free of values. It represents not ‘preconceived notions’ about the world but only ‘ascertained facts.’” Following in this tradition, Lifton asserts that Rockefeller’s mission is to do “good science” as opposed to engaging in “political debate.” Just the same, describing science with a vague modifier like “good” is a political statement in itself, albeit one that is left unexplained. (What is “good” science? Who decides what that means? Donors? Graduate students?) Rather than paraphrasing it, the University’s mission statement should be quoted in full: scientia pro bono humani generis—science for the benefit of humanity. This kind of science necessitates political consciousness and engagement with the world. If the science is in service of capital or if scientists’ timidity and reluctance to debate politics enables the dismantling of scientific research infrastructure, can Rockefeller really claim to be doing science for the benefit of humanity?