I was born and raised in a remote small town in southwest China where transportation was inaccessible, and the economy was underdeveloped. People made a living by planting rice and corn or working as migrant laborers. My hometown of Baiquan, situated on a plateau, was surrounded by towering mountains with no end in sight. From a young age, I was curious about what could be found beyond those peaks, and I dreamed of one day exploring the world.

Baiquan was a place marked by traditional values, where boys were preferred over girls, early marriage and pregnancy were common, gender stereotypes were conserved, and opportunities were limited, especially for women. However, I was lucky enough because my family was a little bit different. Although I was a girl, I had access to education, a right some other girls in my hometown didn’t have.

Growing up in school

As a child, I grew up with my grandparents who were ordinary farmers and had endured a challenging life. They taught me to work hard and live in the moment. My grandfather, in particular, valued education. I can remember that I only scored 17% on my first math exam, but instead of scolding me, he spent the entire summer holiday tutoring me in math. Over time, my scores improved. Whenever I did well, he encouraged me and brought me snacks, which boosted my confidence and interest in studying. Education became my refuge. When I excelled in school, I was exempt from doing household chores that other girls were assigned. No one offered unsolicited advice about my life, and I found that high scores allowed me the freedom that other girls did not have.

The call from science

In middle school, when asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, I randomly answered “scientist”, like my classmates. “Scientist” was a word I heard from teachers and classmates, but I didn’t truly know what it meant. Nevertheless, the seed was planted.

In high school, preparing for the college entrance exam became my entire world. When I finally took the exam, I did well enough to gain admission to a good university in a big city far from my hometown. It was my first time leaving home.

I started my college life with curiosity and excitement, but soon felt a gap between myself and my classmates. I thought that they had more knowledge than me, more experience, more talent, whereas I only knew how to study. Comparing myself to others made me feel an overwhelming sense of inferiority.

In college, I joined the Mathematical Modeling Club, where I met friends who encouraged me and broadened my perspective. They often said, “If it’s gold, it will shine.” They reminded me that everyone’s starting point in life is different–the education they get, their family background … Life experiences are so different, just go towards the direction you want to go, and eventually you will reach it, even if it is a little slower than others. “Compare yourself only to yourself,” they said. That advice inspired me to focus on my own path, which soon included pursuing higher education. After all, I liked studying.

The taste of independence

After I graduated from college, my parents began to interfere more in my life, insisting that it was time to marry and start a family. This was the path women in my hometown typically followed, and girls didn’t need to get higher education. Even my grandfather, who had once emphasized the importance of education, agreed with them. His encouragement had always been limited by traditional expectations of what was “good” for a girl. I was no longer the little girl who was diligent, obedient, and studied well. I was a woman now, and there were different expectations of what was “good”.

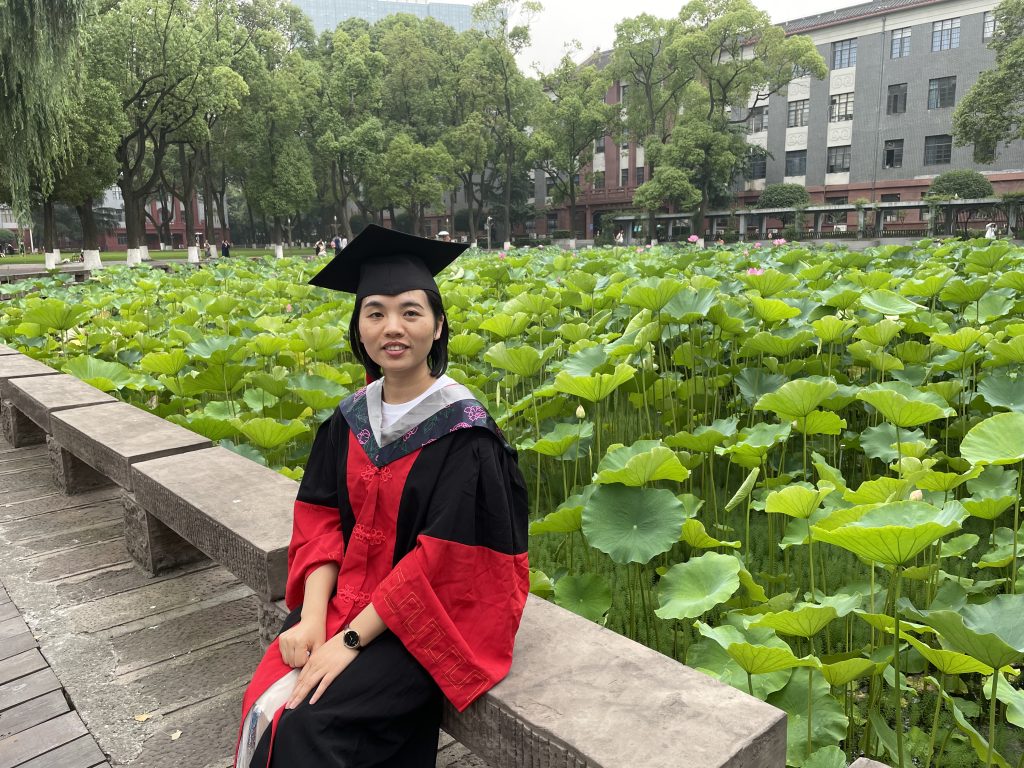

Ignoring my family’s objections, I applied for a master’s program. This marked the beginning of my journey in science. Under my PI’s guidance, I learned how to culture cells and use mice to create models of diabetes. Gradually, I began to enjoy conducting experiments and immersing myself in research. The sense of accomplishment from solving scientific problems fueled my passion for science, and I found fulfillment in publishing research papers. I began to envision a future in academia.

Despite my accomplishments, my parents continued to push me toward a different life. They even arranged a job for me in my hometown, hoping I would return and stay close to them. But I knew I couldn’t follow the path they envisioned for me. I was determined to carve out my own path, even if it meant defying their expectations. From that moment on, I made up my mind to escape from there.

Forging my own path

I decided that my destiny was in my own hands. I wanted to become stronger, more mature, and self-sufficient. I wasn’t going to marry someone and rely on him to solve my problems. I understood that only I could shape my future. I knew that only I could solve my life problems, no one in this world could do it for me.

Driven by my passion for science, I applied for a PhD. I didn’t fully realize how difficult it would be, although I had heard tales of the pressure and stress that PhD students often face. Still, I chose to pursue this path over marriage. In the early years of my PhD, I was optimistic and energized by the idea of making groundbreaking discoveries. But as time went on, my progress slowed. I made little headway on my project for two years, and my initial goals of publishing in an influential journal were replaced by simpler aims of completing my project and graduating.

Completing my PhD took five years, and throughout that time, I struggled under the weight of academic pressure and family expectations. I realized that a PhD was not only intellectually demanding but also physically and emotionally exhausting.

Discovering feminism

As I sought ways to cope with my unhappiness, I stumbled upon podcasts, which introduced me to feminism. Feminism provided me with a new perspective on the world. I began reading the works of Simone de Beauvoir and Chizuko Ueno and learned about the historical struggles and achievements of women who fought for equality. Feminism helped me understand that in my own struggle, I was standing on the shoulders of women who had paved the way for me.

With my newfound understanding, I began to notice gender disparities in my lab. Of the twelve students, only four were women, and we were held to different standards than our male peers. My PI often told us female students not to work so hard, while whenever male students proposed new ideas, he encouraged them. However, when female students asked to try new methods, we were often dismissed. It became clear that women were discouraged from exploring and taking risks.

I can’t say feminism is perfect, but I feel that my life would be incomplete without this perspective. Feminism has brought me a lot of freedom and liberation. It helped me understand that marriage didn’t need to be my primary life goal. Instead, I focused on achieving financial and personal independence, which I realized were key to my happiness and self-fulfillment.

Now I know that I belong

After completing my PhD, I embarked on a new chapter as a scientist in the United States, grateful for the opportunities created by the women who came before me. Inspired by their legacy, I am committed to making meaningful contributions through my research. Even though science is difficult, I firmly believe that my work should leave a positive mark on the world. Ruth Bader Ginsberg once said: “Whatever you choose to do, leave tracks. That means don’t do it just for yourself. You will want to leave the world a little better for your having lived.” My journey, once driven solely by personal ambition, now carries a broader purpose—to stay at the table.

For female scientists, staying at the table means having a place in the scientific community, being able to make our voices heard, and having our ideas valued. It means creating a path for future generations of women, giving them more opportunities and possibilities.

As I sit at the table today, I strive not only to excel in my field but also to pave the way for those who will come after me, working toward a future where women are fully included and respected in science.

Photos provided by Fuhui Meng