Bernie Langs

Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School, by James H. Stubblebine, is a two-volume set of books examining the fascinating period of early Italian Renaissance art from 1285 up to about 1330. The second volume features over 500 black and white photographs of the paintings discussed in volume one, including each of the surviving works of Duccio (b. c1255-60; d. 1319) and many of those by his assistants and fellow artists in Sienna.

Art experts and novices alike prepare their pilgrimages to museums, churches, galleries, and civic and cultural centers by studying ahead of time the artifacts they’ll encounter. Full color and black and white reproductions in books such as Stubblebine’s provide the essential tools for comprehending the history of an original piece, including the painter’s personal background, how his or her creations reflect the historical epoch in which they were constructed, where an individual painting fits into the overall oeuvre of the artist, and the circumstances under which the work of art was commissioned. When lacking detailed primary documentation, art historians painstakingly examine and opine about individual paintings, sculptures, etc., in the hope of identifying the artist who created it.

Reading Stubblebine’s detailed analysis of every known work by Duccio and his school, one senses that the study itself is in some cases as equally gratifying as viewing the actual work of art. The real thing is, of course, usually superlative to the printed duplicate, but that does not take away from the important role played by art historians who share their expertise, supplemented by photographic replicas, to train and prepare dedicated readers on what to look for in the presence of original art.

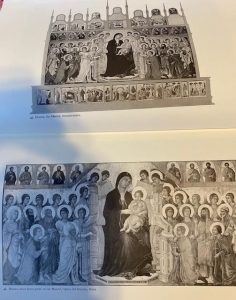

The Maestà is a masterpiece of early Italian Renaissance painting by Duccio and a perfect example of how reading about art assists in the enjoyment of the object. I have viewed reproductions of the central panel of The Maestà for decades, along with the sixty autograph or workshop-produced smaller works that complement it. Upon seeing it in person in Sienna, it became clear that no book, photo, or film could replicate the stunning beauty and overwhelming presence of the painting. The colors are muted yet unexpectedly bright at appropriate times, with the bold central figures of the Virgin and Child surrounded by a multitude of Saints presented in awe-inspiring symmetry. Duccio’s mystic expression is placed within the confines of idealized beauty that’s neither of heavenly eternity, nor set in a static “time and place.” Somehow the subject and painting are also outside the realm of our tangible world.

Stubblebine’s description of the painting in Duccio and His School and the Volume Two book plates are of service in explaining its meaning and where it lies in historical context within the progression of art history. The book’s analysis of the dozens of works created to accompany The Maestà is extraordinarily helpful, since when you are in the presence of such wonder, there’s no conceivable way to take it all in unless you have hours and hours to spend in that one single room, choosing to abandon the multitude of additional treasures that Sienna offers elsewhere. At home, reading in the evening by lamplight, one has the luxury of time and multiple sittings with the book for a careful study of the entire project.

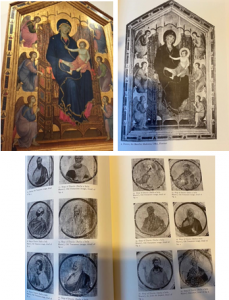

The Rucellai Madonna and its rondels in detail; plates in Vol. 2 of Duccio di Buoninsegna and His School (Two Volumes) by James H. Stubblebine, Princeton University Press; First edition (March 21, 1980) (Photo credit: Bernie Langs).

Duccio’s The Rucellai Madonna (1286) has the honor of being one of the first masterworks on display when entering The Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It is situated close to similarly large wonders by Duccio’s brethren of the late 1200s and early 1300s, Cimabue and Giotto. Reproductions of The Rucellai Madonna are unable to capture its essence and power of presentation, but as with the sixty predella works of The Maestà, there are thirty small rondels surrounding the Virgin, Child, and angels, which most visitors to the museum give but a cursory glance. With an in-depth study such as Stubblebine’s book, the reader is treated to a Sherlock Holmes-like revelation and tale of how art historians identified as best they could who is represented in these small works and what meaning the figures may have held in Duccio’s time.

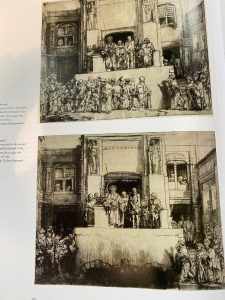

One of Kenneth Clark’s finest books is Rembrandt and the Italian Renaissance (1966), a detailed study of how Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) in his prints and paintings was influenced by the Italian works of art he was most likely exposed to during his lifetime. A memorable sequence in the book is the enthusiastic description of varying states of Rembrandt’s print created in 1665, Christ Presented to the People (Ecce Homo). Clark undertakes an exacting discussion of the architecture of the scene and how Rembrandt developed and made radical changes on the etching’s plate as he worked out the ultimate expression of the scene, aided by what he learned from the Italian masters of the Renaissance. These pages about the prints are in many ways much more interesting than the actual images on paper themselves.

While watching the 2004 movie The Passion of the Christ, I noticed that director Mel Gibson’s set depicting ancient Jerusalem for the Ecce Homo scene of the Christ story owed a great deal to Rembrandt’s print. The movie, dubbed by one film critic as “the most violent film ever made,” displays Ecce Homo as a revelation guided by the director’s use of the setting in which the action unfolds, thereby giving the moment a power unequaled in other films centering on the New Testament. The sequence in The Passion when Pontius Pilate shouts out to the angry mob below him in the ancient square his infamous declaration Ecce Homo! (Behold the Man), enhances the understanding of Rembrandt’s prints as a study in the delicate balance of place and people in art, with classic architecture manipulated in service of religious expression and emotion.

Standing in Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico’s Sala dei Nove to view the fresco series painted by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, The Allegory of Good and Bad Government (1338 and May 1339) is one of life’s great pleasures. I’ve seen countless photos and posters of the walls, which display in a complicated allegory warning to the politicians of late medieval Siena that corruption, dishonesty, and ignoring the will of the people is but a path leading to inevitable disaster. When I walked into the chamber, all of my past “training” seemed to dissipate, and the many chapters I’d read about the cycle’s meaning and history refused to be called forth to consciousness. In addition, I was literally shocked by how many large sections of the frescos had disappeared forever due to the merciless, ravaging Hand of Time, leaving sections of exposed plaster here and there. As I finally began to get my bearings, the wonder of the art overwhelmed me and the sumptuous details of Lorenzetti’s masterpiece spoke of varying joys, pains, dances, and deaths, a wonder of experience.