Top Shelf: A Look at Books in a Personal Library

Bernie Langs

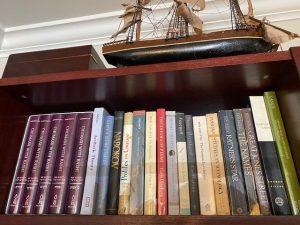

This is a photo of the top shelf of one of my home bookcases. What follows is a brief description of what I’ve taken away from each book and the way in which the author and their ideas changed the course of my thinking for the better.

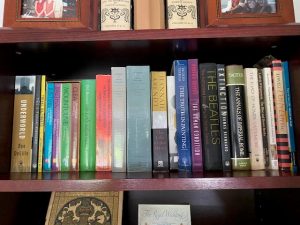

Underworld by Don DeLillo: The novels of Don DeLillo (b. 1936) are filled with uniquely interesting characters often caught in a mysterious web of intellectual deceit, intrigue, and danger. The Names, my personal favorite, has a powerful plot centered on threats of impending murder contrasted with cerebral notions on the nature of language and communication. Ratner’s Star has passages swinging from the deeply disturbing to laugh aloud humor and includes wild debates on the nature of higher mathematics. 1997’s Underworld takes an unflinching look at American society through the lens of numerous alternating plot sequences. Many of these sequences revolve around Bobby Thompson’s “Shot Heard Around the World” homerun in 1951 at the Polo Grounds in New York City and the fate of the baseball picked up that day by a lucky—or unlucky—fan behind the stadium as it changes ownership through the years. This highly original story makes for a grand read.

Yes, Wittgenstein’s Nephew, My Prizes, and Extinction by Thomas Bernhard: I purchased Old Masters by Thomas Bernhard (1931-1989) on a whim in the 1980s, because I liked the cover photo of a Renaissance portrait of a bearded man. Each of the many books that I have voraciously read since by the author garners the same reaction of astonishment that I had after my first experience with his introspective work. All of Bernhard’s books have no paragraphs and feature an unrelenting first-person narrative in the voice of a young or middle-aged man, smart as hell, usually wealthy, and extraordinarily furious at the world. These confessional diatribes initiate on page one and continue unabated up to the last sentence, taking brief detours at times for improbable, well-placed humor. Bernhard consistently appears to be making the observation that the terrors and violence of Western European history remain vibrant and alive to this day—a remnant of cruel, barbarian tribes of Germanica during the age of the Roman Empire as well as the dark, punishing, superstition-based practices of the Medieval Holy Roman Emperor and Church. There is an omniscient psychological and physical cruelty in Bernhard’s novels as his characters live out their lives within a hateful social fabric accepted as the fated price for simply having been born in Austria. Extinction, his final published novel, is a monumental farewell by the author. The first half of the book is a reminiscence in the voice of the protagonist at the moment he’s been informed of the death of his parents in an auto accident, initiating a series of repetitive remembrances of his growing years on his family’s Austrian country estate, Wolfsegg. The second half chronicles the events taking place on his return to his ancestral home, where as executor of Wolfsegg, he confronts his family’s eager acceptance of fascism during the years of Nazi rule. The book closes with a stunning and unexpected decision by the narrator regarding where the entire family fortune and property will be directed in perpetuity. Extinction is a masterful and moving summation of all that Bernhard communicated through his works over his far-too-brief lifetime.

The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell: This set of four books, focusing on a group of friends living in Alexandria, Egypt, was gifted to me decades ago by my brother and was a game-changer in my understanding of what mid-twentieth century literature as an art form could express in emotion and immediacy. These works of Lawrence Durrell (1912-1990) are disturbing at times, and much is made throughout the writings of the Marquis de Sade, so often dismissed as a barbaric writer of cruel sexual titillation. When I tuned into an amusing British-produced television series on PBS, The Durrells in Corfu last year, within minutes I realized that the oldest son, Larry, was none other than the pre-fame Durrell who’d penned the Quartet. I honestly cannot recall many details of the Quartet outside of having enjoyed it immensely.

The Early Italian Poets translated by Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The first edition of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s (1828-1882) collection of Italian verse composed during the Middle Ages was published in 1861. Rossetti was one of the founders of England’s Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and had a career across many genres, including poetry, illustration, and painting. The poems in this collection were written between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. The greatest and most important work is The New Life (La Vita Nuovo), penned by the translator’s namesake, Dante Alighieri. The lengthy poem recounts the supposedly true-to-life emotional moments when Alighieri sees for the first time the (very) young Beatrice, his muse. Beatrice also makes a vital, heavenly appearance in the poet’s masterwork, The Divine Comedy. The Early Italian Poets is also of interest as documentation of how the Italians began to take pride in their native “vulgar” language after centuries ceding anything of literary, religious, or historical value to Latin translation.

The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, and Confessions of a Mask by Yukio Mishima: Yuko Mishima (1925-1970) was the gateway author for my interest in Japanese novels, short stories, and novellas. Reading this collection of novellas and other post-war Japanese writers allows for a more significant (yet admittedly cursory) understanding of the nuances and culture of Japan compared to simply viewing Edo-period ukiyo-e woodblock prints or watching films by Akira Kurosawa. Mishima’s stories often touch on violence and tales of emotional cruelty presented and exposed as characteristic of societal norms, in many ways similar to what Bernhard does with Austria. When reading his final tetralogy, The Sea of Fertility, many readers are aware that immediately after Mishima bundled up the completed manuscript, he proceeded to die by his own hand in an act of ritual seppuku. Mishima stands tallest of the many Japanese writers I’ve enjoyed, with his bold and stark observances of life in post-World War II Japan. The currently popular writer, Haruki Murakami, continues Mishima’s tradition of upsetting and disturbing their nation’s applecart.

A History of Chinese Philosophy, Volumes I & II edited by Fung Yu-Lan: It’s a huge commitment of time when a reader takes on a book of this scope and size. Later I would read a similar compendium, A Sourcebook of Chinese Philosophy, to solidify the structure of thought built atop this foundation. The chapters are prefaced by Fung Yu-Lan’s introductory explanations about the selections by ancient writers who established the course of centuries of Chinese thinking. Works of Confucianism, Neo-Confucianism, and the poetic glosses of the Tao de Ching by Loa Tzu and Chung-tzu act as calming meditative balm to the reader. A most memorable chapter, The Eight Levels of Consciousness, presents an elegant treatise describing how during the ebb and flow of reality from one nanosecond to the next, the fabric of life, thought, and the physical world, is seamlessly born anew again and again. The description of how this occurs within the sizzling cauldron of white-hot, shining “perfumed seeds” is comparable to digging down to string theory level to explain how the space-time continuum folds out dimensionally from the subatomic level to form the visual world we take for granted as the ubiquitous space in which we go about our daily lives.

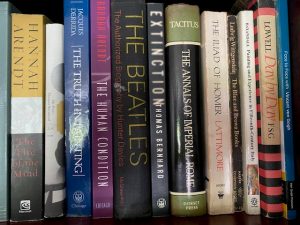

The Life of the Mind and The Human Condition by Hannah Arendt, The Truth in Painting by Jacques Derrida, and The Blue and Brown Books by Ludwig Wittgenstein: I read the books by Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) in 1977 in college and recall asking the professor, “Is it my imagination or whenever Wittgenstein is on the cusp of culminating an idea, he slowly drifts off to a different subject?” to which he replied, “You’re catching on!” Many believe that Wittgenstein’s books cannot be understood outside of those working at the doctoral level of philosophical expertise. Jacques Derrida (1930-2004), who rose to the level of intellectual superstar, has also been dismissed at times for being a writer of equally confounding absurdity. I find Derrida and his method of deconstruction difficult reading yet tinged with wonderful moments of revelation and humor. The collection in The Truth in Painting and the post-9/11 interview published in 2003 in Philosophy in a Time of Terror proves that philosophy remains a vital method for understanding and explaining how and why we’ve intellectually arrived at this point in history amid ubiquitous turmoil.

The Life of the Mind and The Human Condition are admired as the greatest achievements of Hannah Arendt’s (1906-1975) intellectual career. In these books as in other essays, she expounds, for conclusive purposes of her own perspective, on the many vital ideas of Western philosophy as powerful credos by which to live a moral life. She delivers to her readers the concise “greatest hits” of essential philosophers such as Hegel, her former teacher, Heidegger, and a host of ancient Greek and Roman thinkers and orators. She also writes brilliantly about passages from the writings of Saint Augustine and Saint Paul, revealing their groundbreaking thinking on subjects such as free will and how “grace” may be understood as a philosophical construct.

The Beatles: The Authorized Biography by Hunter Davies: The volume displayed in the photo is the edition I purchased in 1968 when I was eleven years old (the cover is sadly lost). Released while The Fab Four were still a working band and recording their songs for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour, Hunter Davies (b. 1936) followed the group to the recording studio and their homes, having been granted unprecedented private access to all four Beatles. The Authorized Biography was my first experience with swear words on the printed page, and I recall my surprise at how much of what John Lennon said had such a harsh tone, contrasting with the public image the band had maintained up to that point. The late-1960s reader finally met the Beatles as actual, honest individuals in this biography, their lives displayed warts and all, with stresses and pains more common to our own experience than perhaps we’d wished to learn.

The Annals of Imperial Rome by Tacitus and Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy by Michael Baxandall: Tacitus (56 – c.120 A.D.) was a Roman politician and historical author living during the reign of the Caesars. He gives an erudite and exciting history in the Annals of the days of the earliest post-Augustan rulers, Tiberius and Nero, both of whom descended into violent behavior as a form of political terror. Tacitus is a fabulous, yet strict storyteller and the reader marvels at the intimate details of the many larger than life historical figures that make appearances in the book.

An understanding of ancient Roman art and life is a must if one wants to fully appreciate the classical themes invoked in Renaissance art and architecture. Art historian Michael Baxandall (1933-2008) believed that when looking at Italian paintings, pagan and Christian themes held meanings in fifteenth and sixteenth century Italy, often overlooked by the modern viewer. Painting and Experience is a great addition to the works of scholars who believe that educated beholders of art must engage and open their minds to the culture and mores of the society in which a piece was produced. This approach is still a subjective one, and is actually more akin to a feat of imagination than science, yet the iconography explained in this book goes a long way in assisting viewers seeking to fully experience the lessons and beauty of Italian paintings.

The Iliad of Homer translated by Richmond Latimore: There is something in this ancient epic that inexplicably resonates with me, and I’ve read it three times. The classical Greek mind developed and rapidly progressed after the volatile Dark Age, morphing through the Pre-Socratic schools into the Classical Period, the Golden Age of Greece. That entire artistic and intellectual advancement was pushed to birth by Homer’s Iliad and the later Odyssey. Many ancient epics are thought to be compilations of songs and stories passed on for centuries as sacred oral traditions that were eventually codified. The Iliad revolves around the interaction between men and women with each other as well as the gods and goddesses influencing them, often without their knowledge. It presents an exaggerated, imaginative remembrance of what may (or may not) have been the causes and events of the historical Trojan War. Homer’s telling has a texture of action and dialogue not found in similar heroic tales of past ages or those by Hesiod and other contemporaries of Homer. This opened the door to writers, poets, playwrights, and philosophers who began to use a more measured, organized, and rational voice.

The last two books on the top shelf are Robert Lowell’s collection of poems, Day by Day, which my mother owned and kept on her bookshelf for many years, and Face to Face With Vincent van Gogh, a small book of Vincent’s paintings gifted to me by daughter on her return from Amsterdam in January 2020. The emotions elicited by these two books from my late mom and my recently college-graduated daughter are best related here in the words of Tom Hanks as Captain Miller in the film, Saving Private Ryan. During the final minutes of calm before the storm of the film’s furious final battle, Private Ryan (Matt Damon) graphically and happily tells the intimate and long story of how he spent his last night at home in Iowa with his three now deceased brothers, all of whom he has just learned to have been killed in the war. When he’s finished, he asks Miller to speak from his heart about the Captain’s wife and how she tends her garden and their rose bushes at their home, to which Miller softly replies, “No, no—that one I save just for me.”