Films of Exploration and Adventure: The Lost City of Z and The Lighthouse

Bernie Langs

Spoiler alert below!

In the time of movies featuring a multitude of superhero comic book stories, cliched comedies, and explosive action adventures with mindless plots and throw away dialogue, we can still rejoice knowing that studios will occasionally take chances on more complex and thoughtful cinematic ventures. The box office and critical success of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women and the sophisticated comedic murder mystery Knives Out come to mind. There are other genres to be found by audiences among the artistic rubble of the explosions presented in many blockbuster stories. These include thought-provoking tales of adventure and period pieces delving into the psyche of obsessive individuals stretched to the breaking point. Two recent movies are grand examples of this: The Lost City of Z (2016) and The Lighthouse (2019).

The Lost City of Z is a creatively intellectual and extremely entertaining movie. Directed by James Gray, who also wrote the screenplay, the story is based on the book of the same title by David Grann. Z centers on the true events of the life of explorer Percy Fawcett, played with nuance, bravery, and dashing elegance by the English actor Charlie Hunnam. As a British military officer in the early years of the twentieth century, Fawcett is unexpectedly conscripted against his career wishes by the Royal Geographic Society and the British government to lead a surveying expedition and settle a boundary dispute between Bolivia and Brazil that will have important implications for the lucrative rubber trade and industry. Fawcett’s transformation from an unwilling participant in the discoveries of uncharted Amazon into an excited and obsessed groundbreaking explorer is a captivating and endearing tale.

Hunnam’s portrayal of the understated Fawcett is a work of art as he survives the trials and tribulations of disease-ridden jungle and river exploration. Fawcett is at times forced to act quickly and with daring imagination to find life-saving ways to communicate that his team comes in peace to wary native inhabitants. On his return to London, he must deal with resistance from the Royal Geographic Society’s snobbish members about the possibility of a lost city—a previously unknown, sophisticated ancient civilization in the Amazon, which the Society deems “savage.”

In addition, Fawcett has to justify and explain his years of absence to his growing eldest son, and the limits of his enlightenment are tested as he struggles to recognize and fully respect the intellectual equality of his wife. Sienna Miller lights up the screen as Nina Fawcett, who suffers for years worrying for the safety of her husband and bearing the sole responsibility of raising their children. Percy Fawcett eventually manages to learn from and understand Nina, and there are emotional moments in the movie as his son starts to idolize his father’s courageous exploits and even secures funding for further exploration from the likes of U.S. newspapers and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Father and son (the latter now a young man), set out together into the danger-filled Amazon for a final attempt to locate the Lost City, now experienced simultaneously as both an ancient reality and a fragment of a dream within the explorer’s psyche.

Robert Pattinson is fantastic in his role as Fawcett’s second in command, Corporal Henry Costin. He is smart and witty, and the actor hides his Twilight good looks under a beard and a ravaged explorer’s body. Pattison’s Costin is a throwback to the sidekick companion of old-timey movies and we delight in his growing devotion to and friendship with Fawcett.

Quality films set in the past that delve deep into the inner psychology of men and women plagued by labors that take them to the limits of sanity are few and far between. Director John Huston’s 1956 adaptation of the novel Moby Dick (1956), for example, showcases Gregory Peck as the infamously tormented Captain Ahab. Ahab’s rage and quest to kill the white whale not only boils to overt fury and self-destructive action, but also softly simmers during his rational, quiet conversations with officers of his crew.

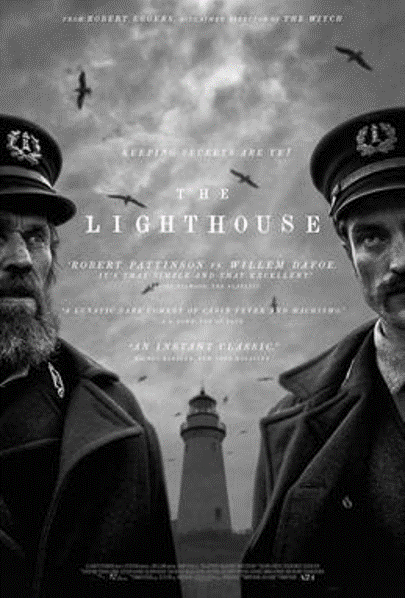

Melville wrote his sea adventure in 1851 and set the launch of the doomed Pequod from New Bedford, Massachusetts. Robert Eggers’ film The Lighthouse also takes place in the late nineteenth century and is set somewhere in northern New England. Actors Willem Dafoe as Thomas Wake, and (once again) Robert Pattinson as Thomas Howard/Ephraim Winslow, are paired together to work a stint at a lighthouse on a tiny island, with Wake as the older and more experienced keeper. The backbreaking work amid lonely isolation leads to more and more sarcastic bickering and stinging jabs and arguments, and the two men reach a breaking point when they realize that the team scheduled to relieve them from their duties is not going to appear and allow them to return to the mainland.

With its unrelenting barrage of crazed situations and behaviors, I would not recommend that everyone see The Lighthouse. Prior to viewing the film, I read some superlative reviews touting the incredible acting by Dafoe and Pattinson and I did find their superlative portrayals worthy of Academy Awards. The audience is also treated to a study in black and white cinematography and the unusual horizontal shrinking of the actual film space. This “narrow vintage aspect ratio” gives the movie a more realistic nineteenth century feel and enhances the mood of stress in the claustrophobic living space shared by the duo. As the two main characters become more and more unhinged, the dive into their insanity plays out like a fascinating live theater-like stage rendition of immediate violence. There are mystic hints of a moral and religious reckoning, complete with chilling visions of hallucinatory mermaids and sea gods. The mystery of the blinding white light of the tower lantern of the lighthouse becomes a powerfully charged character on its own, an unknown entity, which may be abstractly fueling the deadly struggle between its two attendants.

As I left the multiplex after The Lighthouse, I was in a state of shock from the continuous horror the pair go through and inflict on each other, and although I didn’t “like” the experience, I (sort of) inexplicably did, and plan to watch it again as a rented movie at home. The interactions between Dafoe and Pattinson bounce around the emotional spectrum and the destruction of their lives and souls unravels and unfurls with a rarely viewed intensity, one without relief or pause for the audience to take a breath in recovery. The movie’s greatest moment, oddly tinted with humor, initiates as a petty argument over the quality of Wake’s cooking and ends up devolving into the fury of a legendary curse invoked by him upon the life and soul of his young worker. Dafoe masterfully delivers a harsh, yet poetic verbal assault, piling up a list of vengeances that draw from the history of sailors’ myths and fears. Dafoe’s character also dives deep into plagues worthy of the Old Testament on the life of his hapless co-worker. That speech alone makes The Lighthouse worth the viewing. The Lighthouse ends with a new take on violently creative punishments, reminiscent of those in ancient Greek mythology. That brand of complex allusion is what draws filmgoers to sit through such a difficult and hard-to-take story.