Bernie Langs

Late 20th century philosophy took a longwinded detour from practical thought with its micro-analysis on the importance of the structure of language, but there is one idea that emerged that I find of great interest. It is the notion that once an author writes a work of literature and publishes it for a wide array of readers, in some manner the writer relinquishes his or her rights as the sole proprietor of the work. Since the reader is drawing from their own experiences, what is created in their minds brings whole new meanings, imaginations, and so on beyond the control of the original author’s intention.

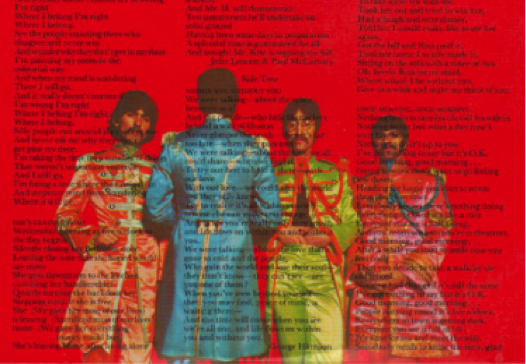

Along those lines, I would suggest that after The Beatles (George Harrison, Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney and John Lennon) laid down the instrumentation and vocals for the songs on the 1967 masterpiece Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band with George Martin producing and scoring the orchestral charts and Geoff Emerick at the helm as engineer, the meaning of the work was passed on to their multitude of listeners as individuals. What follows here is a song-by-song analysis of my personal notion of Sgt. Pepper’s.

The LP opens to the sounds of a mulling crowd outdoors, awaiting the stage appearance of a good-time band, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. A distant, surreal wave of an accordion invites the listener to join the pleasant afternoon outing. After the misery of touring and the madness of Beatlemania, McCartney devised the concept of Sgt. Pepper’s as a Beatles’ alter-ego group, who would perform the album. The famous first lines, “It was twenty years ago today, Sgt. Pepper taught the band to play,” nods to an imagined, sweet nostalgia. The guitars are on the heavy side and Martin introduces the first break with bold horns as the crowd elicits a peal of laughter to some antic on the bandshell they are witnessing.

McCartney enthusiastically tells us in his vocalization about what we will be hearing in the “live performance” to follow, and sends the cheering crowd off to listen to singer, “Billy Shears.” We’re seamlessly led next to the quieter studio sound of Starr singing With a Little Help from My Friends. The acoustics and overall sound of Pepper’s is immediately discovered to be new for The Beatles. The mature period of the band began with its two previous albums, Rubber Soul and Revolver, each boasting revolutionary songwriting and production, but still maintaining a loose feel in sections. Pepper’s, on the other hand, is musically and sonically perfect and The Beatles sang or played take after take to make sure it would be so. It’s incredibly cleanly produced and also very tightly bound, as if the band knew their efforts would be examined and listened to for many decades. This near sterility contrasts sharply with The Beatle’s swan song, Abbey Road. that is also technically perfect but very warm in production.

Starr sings his best ever vocal on Friends, and it is said the other members of the group were standing next to him as he sang, to lend confidence and support to the drummer. Beatles’ biographer Hunter Davies was in the room when the song was composed and as the group threw around ideas for the lyrics. It is exciting to read his account of which ideas were encouraged and which were discarded.

Friends boasts lyrics about how we all support each other, and though it is very much a song about interpersonal relationships, there are some enigmatic ideas floating about. Lennon’s Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds is next in queue and veers the LP to the direction it will follow until completion. To call it “psychedelic” is accurate, but almost a bit of a trivialization. Lucy creates an incredible world of colors, situations, and improbabilities, with harmonized background singing experienced as if in a waking dream. Lennon’s enthusiastic lead vocal invites us to this land of improbable wonders and McCartney’s wandering bass line and chorus harmonies are strong. The tune’s instrumentation is less than obvious, including the fun, two-fingered ditties of an organ during the final robust rounds of the chorus.

The next three songs on side one are mostly McCartney-penned compositions, with touches of Lennon. It’s Getting Better All the Time and Fixing a Hole approach a similar concept from different angles. McCartney’s innate positive attitude bursts forward in Getting Better and Lennon tempers McCartney’s cries of “I have to admit it’s getting better, a little better all the time” with the choral harmony of “it can’t get no worse.” When the song goes dark, with a drone chord and the terrible admission of past cruelties to women, it soon returns with the promise of being set straight, life’s course corrected. Harrison and Lennon power through Getting Better with tight chords played in unison on unexpected frets, adding sharp crispness to the verses that are relieved with the beauty and phrasing of the chorus.

After the uniquely abstract meditation of Fixing a Hole, we’re brought to a song very much of the times, She’s Leaving Home, which has no pop instruments at all, featuring strings and a prominent harp. It’s a story of a young woman quietly slipping out of her parent’s home, where her father awakens to find her note of goodbye to which he breaks down in tears. It reflects a generation taking leave of the customs of a stricter era while remaining sensitive to the pain caused to the families engulfed in the turbulence of the 1960s.

Side one of Pepper’s concludes with Lennon’s mischievous, dreamy, minor-keyed composition, Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite, much of which is lyrically borrowed from an old circus poster in Lennon’s possession. For the solo portions, the Beatles created fascinating loops, which were activated at precise moments in the recording process, featuring all kinds of beautiful organ, keyboard, and primitive synth-like music that flows in and out and all over the mind of the listener.

Harrison’s song Within You Without You opens side two with the drone of sitars and the beat of a tabla and other instruments from India. Harrison had found the spirituality of the Hindu religion and traveled to India to discover its history and culture. During the Sgt. Pepper’s sessions and in subsequent years, Harrison’s interest in the group often waned because he felt an impetus to follow a new spiritual journey of which being a Beatle was nothing but a hindrance. Within You Without You is a heavy meditation of life’s purpose and on those who waste their time and chances to do good while on this earth. Yet it ends with a strange laughter, as if people at a small dinner party, having indulged in too much wine, laugh off their prior “deep” conversation.

McCartney follows with two delightful little ditties, the fun When I’m Sixty-Four featuring an awesome clarinet arrangement by Martin and the amusing Lovely Rita about a young man wooing a stern British meter maid, with an incredibly tasteful piano solo, also played by Martin. After the spacey finish of Rita the album kicks into high gear towards its completion with Lennon’s Good Morning Good Morning. The Beatles are looking at life in earnest here, the mundane slogans of a breakfast cereal mocked to reveal a strong and frustrated young man in his prime going through his day. “Nothing to do to save his life” Lennon sings, and we follow the youth as he flirts with women on the street and heads to town where “everything is closed it’s like a ruin.” Harrison unleashes a brief, brilliant and crazed guitar solo from which Lennon’s flights of fancy return amid a brash Rock ’n’ Roll horn section.

Good Morning has a famous fade-out where the madness of the repeated chorus gives way to sounds of barnyard animals, to a point at which a single clucking chicken is transformed into two loud guitar notes for the reprise of the opening song Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The mock group of Sgt. Pepper’s bids farewell to its outdoor audience, as the guitars pulse wildly and Starr pounds a basic four-four beat as if he’s powering a huge airplane for liftoff.

Amid the sounds of the crowd cheering, Sgt. Pepper’s band fades away in goodbye, and for the last track, The Beatles return as themselves, to play the masterpiece, A Day in the Life. Lennon wrote the song’s backbone, with its poignant ruminations on bits and pieces he’d gleaned from newspaper or television stories and from his own acting experience in the Richard Lester film How I Won the War. There is a light and wistful, yet playful atmosphere to the recounting of sad news or oddities such as the discovery of “four thousand holes in Blackburn, Lancashire.” The opening section segues through a mad orchestration played by 40 musicians who were given the basic instruction to climb higher and higher on their instruments, but not in unison. Their climactic resolution flows into McCartney’s section, which follows the day in the life of a working bloke. It initiates with the singing of “Got up, got out of bed, dragged a comb across my head,” and ends with the profound frustration of this youth at his office, with McCartney strongly singing “Found my way upstairs and had a smoke, somebody spoke and I went into a dream,” the dream being the reality of what happens during a day of rote work, of labor for labor’s sake, a deflection and diversion from the mind’s natural course.

McCartney’s dream is enhanced by a tuneful melodic buildup by the orchestra and it bounces from its height back to Lennon’s upbeat return with the main theme. The last lyric of the album, “I’d love to turn you on,” brings back the rising, fast-paced orchestra, and Sgt. Pepper’s ends with the orchestra’s crescendo followed by a resolution chord played on five separate pianos by each Beatle and Martin. Their chords are pedaled to sustain until they can sustain no more, as if a distant thunder remains vaguely in the ear rippling on forever in the distance. I’ve never understood that chord, never comprehended why they chose to do it and why they chose to close out the album that way.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is endless for me, I could listen to it every week for the rest of my life and love it on each occasion and hear new things each time with new ideas reigning down on my life. I find the whole thing blissful and often beyond structured thoughts or words.