Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism and the 2016 Presidential Election

Bernie Langs

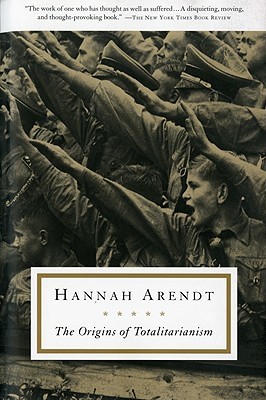

I am close to finishing a masterpiece of historical and philosophical discussion written by Hannah Arendt (1906 – 1975), The Origins of Totalitarianism. My purpose in writing about this book is not to convince anyone to read it, because it is an extremely dense and difficult nonfiction tome. I subscribe to my belief in a “trickle-up” theory, that if certain opinions get into the public sphere, perhaps they will rise not only to the level of a wider public discourse, but eventually reach someone who has influence somewhere in the chain of actual political power.

Dr. Arendt’s book is a painstaking view on how Hitler and the Nazis and the likes of Joseph Stalin could create the totalitarian states in Germany and Russia, which depended on cooperation and coercion to their purposes of the existing political and military structures and personnel, along with crafting an agenda that would attract and integrate their general populations to their ideologies. I think that many of us believe we know how this happened. My personal narrative went something like this before I picked up this book: Hitler rode a tide of German resentment after its defeat in World War One, taking advantage of the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles, economic calamities such as monetary inflation and unemployment, and utilizing as “scapegoats” the Jewish population with relentless propaganda and attacks. The choice of the Jews for Nazi hate and annihilation, I believed, was the remnant and culmination of medieval Christian anti-Semitism which basked in physical attacks on Jews for hundreds of years.

Aristotle wrote in his work, Politics “…it is evident that the state is a creation of nature, and that man is by nature a political animal…Nature, as we often say, makes nothing in vain, and man is the only animal whom she has endowed with the gift of speech…And it is a characteristic of man that he alone has any sense of good and evil, of just and unjust…and the association of living beings who have this sense makes a family and a state.” I have always instinctively fought against and disliked this idea, mostly because I sense that if man is a political being, unlike the Greek’s belief that it leads to the common good, it is political nature that leads the species down the path to horrific events such as the Second World War and the Holocaust. And it was the “gift of speech” that was the incalculably helpful ally in the rise of the Nazis and the Bolsheviks that unleashed terror on the world that left countless millions dead.

After reading just the first few pages of The Origins, my idea of what caused the war (and why Hitler chose the Jews to attack) was shamefully exposed not only as overly simplistic, but downright ignorant. The first edition of the book appeared in the late 1940s and was revised over the next few decades for subsequent publications. I went in thinking I would take what I could from it, given that it is half a century old, and that in this current age of information, this is only Dr. Arendt’s view, and there are most likely many historians and social scientists who carefully refute her claims and ideas. But the real point is that Dr. Arendt doesn’t just study the post-Great War European climate to get to the causes of the unspeakable and well-organized slaughter, but meticulously traces it back to the late eighteenth century revolutions and the societies of the nineteenth century, showing how the situation slowly simmered to the boiling point of carnage. In this book we journey through France’s Dreyfus debacle and relive the nightmare of British imperialism. We follow both large and small political and social movements that are racist, jingoistic, hateful, and so on, some of which resonated with the populace of Europe, some that had no success, but all of which set the table for the rise to totalitarianism as practiced by Hitler and Stalin. There is an in-depth study of post-World War One stateless peoples of the European continent, noting how this sense of limbo experienced by millions gave rise to the horrific solutions offered by the Nazis. The Nazi ideology also finally gave an inclusive purpose to the listless masses of not only Germany, but other European nations as well, the breadth of which I had previously not been aware of.

In addition, Dr. Arendt examines how the American and French revolutions begat a seismic shift to the idea of individual rights for humans, in that people were no longer inherently at the mercy of either a King or of God and the Church, but had an innate freedom beholden to none. But these rights, as intellectually promising and philosophically attractive as they may seem, offered nothing to displaced people who could claim no physical country, and this became a way of defining them as less than human in the eyes of the Nazis.

The rub is that to get to the kernel of any kind of truth, you have to read and dig, you can’t just easily summarize on a whim. And of course you can’t go through two centuries of documents and emerge with an absolute truth of the causes of events, which would only leave you waving your findings like Chamberlain boasting “Peace for our time” just moments before the ensuing bloodbath. But Dr. Arendt’s approach is remarkable and encourages meticulous, difficult, and time-consuming study to get to the heart of an idea of cause.

Finally, although the situation in the 1930s offers similarities to current American political events, it is not a mirror and one of the lessons of The Origins is that there are no absolutely predictable historical outcomes, which was one of the terrible ideas promoted by the Soviets and Nazis. However, Dr. Arendt does warn that the ramifications of the unique totalitarian systems that arose in Russia and Germany in the twentieth century irrevocably changed the nature of international states and politics, giving rise to unexpected new forms of national instabilities and destructive political qualities.

The flaws on display of American democracy in the 2016 Presidential election, especially given the autocratic nature of Donald Trump and his appeal to the so-called “disenfranchised masses”, can in no way be compared to Bolshevik

Russia and Nazi Germany. Those governments had at their epicenters a crazed lone leader constructing a system to support their wild ideals, and Hitler and Stalin depended on the structure of an intricate secret police to facilitate their terror. Even at its worst, American secretive government agencies would never go to the extremes of the totalitarianism societies that planned the deaths of groups of people in advance. Yet, U.S. citizens do quietly acquiesce to certain methods that arose in the last century, such as growing surveillance and the surrender of other rights of privacy. Stalin liquidated enemies who potentially could have just a thought of turning on his crazed governing apparatus, and at times, Americans experience “profiling” by the police well ahead of any actual transgression. But it’s a long distance between the two.

The bluster of Donald Trump in his speeches on refugees and the immigration system are incredibly reminiscent of the way post-World War One peoples facing similar situations were spoken of at that time. Those peoples were given no home of their own, and were bounced around Europe, eventually giving the strongmen of Germany and Russia the chance to step in as nationalist ideologues with carte blanch to fix the problem. And that led to the total surrender of rights, soon to be followed by wide-spread murder. It is not realistic in America to fear that Donald Trump will round up immigrants or refugees for extinction. But just the idea of someone running on a platform of rounding them up in any way should be a cause for great concern.