Johannes Buheitel

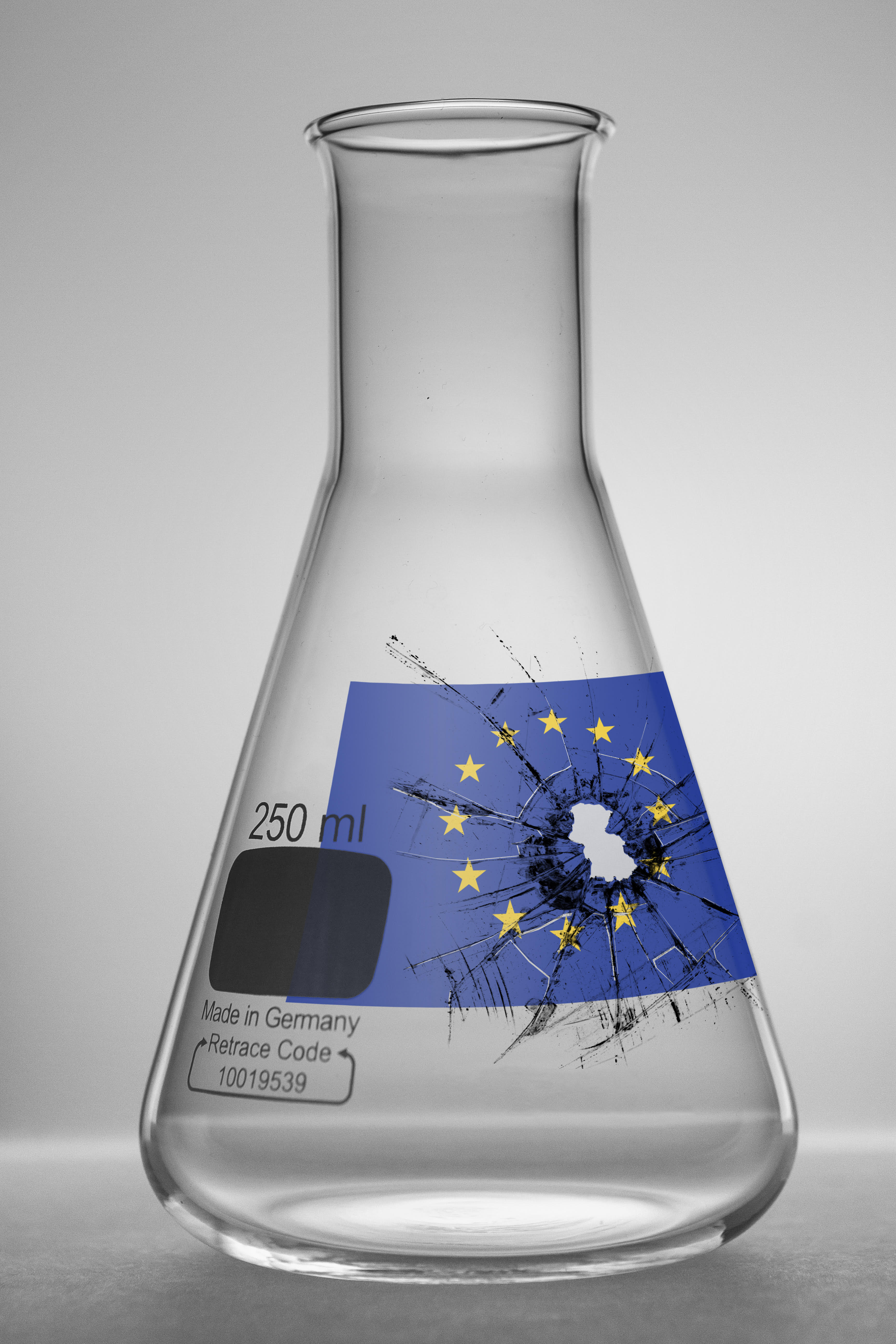

David Cameron looked tired but determined, as he took on the short walk from his front door to the podium opposite a battery of journalists that had congregated in front of London’s 10 Downing Street. On June 24, England’s Prime Minister announced that he will be stepping down from his post October as a consequence of the British people voting to exit the European Union (EU). Even though David Cameron went on to ensure that he will do his best to “steady the ship over the coming weeks” but that he will not be “the captain that steers [the United Kingdom] to its next destination”, it is hard to shake off the feeling that he chose this metaphor for more reasons than he cares to admit in front of the cameras.

As the shockwaves of the Brexit decision rippled through the continent, they inevitably also reached the European scientific communities, which are left in shock and confusion about the future. Because, like so many others, they were not expecting this outcome. Three months before the referendum the renowned scientific journal Nature (based in London) reached out to over 900 active researchers in the UK to ask them about their feelings toward a possible Brexit. A whopping 83% wanted Britain to remain in the EU, a number that is almost double that of the polls among the general population at that time. Most of these researchers explained their vote with the belief that Brexit would harm UK science, which, given the extensive ties between European scientific communities and the EU, seems very likely. According to Times Higher Education, UK universities have received roughly 1.4 billion euros (1.5 billion US dollars) of funding from EU programs per year; funding, that is bound to dry up once Brexit has been completed. Whether this impending gap can be filled by the UK’s domestic budget is unclear. It is specifically this state of limbo that makes UK researchers worry the most. Not even the EU’s Science Research and Innovation Commissioner, Carlos Moedas, has many words of solace to offer and notes that “all implications […] will have to be addressed in due course”

But it’s not only funding that worries UK researchers. Brexit could pose new moving and working restrictions for non-British EU nationals, which make up about 15% of the UK’s scientific community. The upcoming Brexit negotiations will determine whether they will be allowed to stay and work in the UK but the more important question might be, do they want to? In addition to the worries about EU funding in the aftermath of the referendum, there have been reports about xenophobic incidents at British research institutions such as the Royal Society of Chemistry, where some of the staff were told to “go home.”

Apart from principal investigators and postdocs, Brexit also has students looking towards an unclear future. Since the inception of the EU’s student exchange program ERASMUS, the UK has been one of the prime destinations for students from all over Europe. UK’s exit from the EU will very likely not only mean that fewer foreign students will come to Britain but also deprive future generations of its students (about 200,000 British students have benefited from ERASMUS so far) from the educational and cultural experience that the ERASMUS program stands for. These foreign academics helped to generate 37.000 local jobs and around 3.7 billion pounds sterling (4.8 billion US dollar) for the UK economy from 2012-2013 alone, according to Universities UK.

At the moment, we can only speculate as to exactly how Brexit will play out for scientists in the UK and the rest of Europe. But we know that the remaining EU member states have no intentions of making the transition particularly easy for the UK as, has already been implied by leading politicians. Moreover, not too long ago, the EU demonstrated strong determination for maintaining their values when the people of Switzerland (a non EU-member, who maintained extensive relations with the EU) decided to introduce strict immigration quotas. You can read more about how these actions affected Switzerland’s access to EU-based science funding in an accompanying article in this issue of Natural Selections by Juliette Wipf. The only thing that seems almost certain, is that this vessel will be in for a rough ride, but more troublingly, that its very own captain does not want to be caught on it, in case it sinks.