Learning Lessons from Multi-Volume Series

By Bernie Langs

There is no challenge in reading more rigorous than the study, over several years, of a series of books by a single author on one subject. From about 1983 through the late 1990s, I read four series, two of which I did not complete and two of which I finished, that changed my outlook on life.

My first foray began when I chanced on the first volume of a series by the German art historian and curator Max J. Friedländer (1867–1958) and decided on the spot that “I’m going to read all of this.” The 14-volume Van Eyck to Breughel: Early Netherlandish Painting is a wonderful overview of the Northern Renaissance. It’s written from the point of view of not only an art historian, but a connoisseur and a man with emotional and impeccable vision for classifying, cataloging, and appreciating the mostly Christian iconographic paintings of the mid-15th through mid-16th century. The first volume focuses on Jan Van Eyck and his mysterious brother Hubert, who died at an early age, and whose contributions to their oeuvre has been the subject of intense debate through history. The seriousness and depth of Van Eyck’s work, with its rich palette and texture brought on by his groundbreaking use of oil solutions in his paint, bring the reader into a new world of intensity and vitality, that Friedländer is able to maintain throughout the entire work. As the reader progresses, his or her own personal vision is enhanced and improved because of the time spent looking at the 2000 or so plates of reproductions of Masters, such as the harsh Rogier van der Weyden, the idealist Hugo van der Goes, the mischievous Bosch, the sublime Gerard David, and the romantic Adrianne Yesenbrandt, much of whose work I could see on view in the large Northern collection of the Metropolitan Museum.

The way I saw the world changed from the experience, and although I am not of Christian faith, I appreciated that these paintings were a way of an artist’s expression of his or her belief in “The Divine.” The views depicted in the background of many of the works of late Medieval and Renaissance Northern cities such as Bruges, often bathed in dark bluish color and light, became for me an ideal of a celestial home.

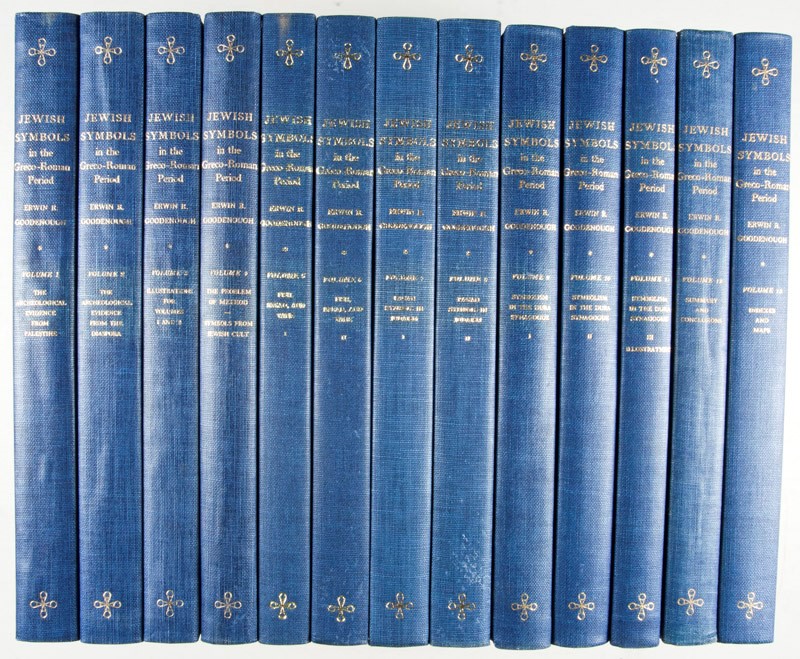

My next foray into a lengthy series was a difficult four-year journey through the ancient world with Professor Erwin R. Goodenough (1893–1965) of Yale University. His masterwork, Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period is sophisticated and dense in presentation. Much of the early volumes are spent defining and refining the concept of what a symbol actually is and how deeply it was ingrained in the psyche of the ancient world in synchronized fashion, so that the Greeks and Romans and even the Egyptians and Assyrians shared ideas of mysticism which were co-opted into Jewish religious expression. Symbols such as divine fluids of wine, or expressions reflecting the stars and the zodiac, or of more natural subjects, show up in the most unexpected ways throughout the ancient world if you are educated to understand what you are seeing.

Goodenough’s life work is steeped in ancient mysticism and Greek philosophers as varied as Plato and Philo. He is quite cognizant that if his readers have stuck with him through his trek, they would emerge changed persons in understanding how we’ve spiritually come to our own world. Some of the photos of obscure ancient sites and artifacts were at times disturbing in their undercurrent of death and the complexities of the fate of the soul. The last volumes are dedicated to the ancient synagogue at Dura-Europas in Syria, where, in the first centuries of the common era, there were places of worship for Jews, Christians and pagans alike. He expertly takes his readers through the remains of the city and synagogue’s beautifully preserved murals and it’s an amazing journey.

Over two decades I read books in the 18-volume series by Salo W. Baron (1895-1989) A Social and Religious History of the Jews. I was raised Jewish but found the weekend temple liturgy tedious. But reading Baron’s books in conjunction with Goodenough’s tracing of ancient Jewish mysticism awoke a unique idea in me of what it means to be Jewish. Baron’s work, especially the volumes on the ancient and Medieval Jewish world, were an eye- opener. His use of source documents is incredibly exciting in relation to Jewish European communities and their leading scholars. One learns of the mistreatment through history of the Jews. To see the detail of the organized hatred of the people, from the Church to the governments of these poor “students of the book,” is horrifying to say the least. Baron’s footnotes are rigorous and lengthy and it’s amazing how many books and treatises and papers he examined over the years.

I read 16 volumes of Baron and ran out of steam. I hope to one day finish the final two volumes. I also didn’t finish Osvald Sirén‘s (1879-1966) series Chinese Painting: Leading Masters and Principles. I was reading it in the library where I was studying for my Master’s degree, and I graduated before finishing the work. I struggled to retain the sometimes complex names of the great painters in the Chinese tradition, but learned valuable lessons on their sublime brushstrokes and how the many schools were classified. Once again, the Met Museum, rich with Chinese scrolls, served me well to see examples of the paintings firsthand. After the often brutal depictions from the Northern Renaissance of crucifixions and gory deaths of saints, the ethereal landscapes of Chinese paintings are a welcome escape and I often meditate on their delicate depictions of serene mountains, lakes and pavilions.