By Bernie Langs

By roundabout way of introducing this museum review, there is a funny scene in Woody Allen’s film comedy Midnight in Paris when, after having visited the Rodin Museum accompanied by a know-it-all art history buff, Owen Wilson returns there alone and asks the docent (Carla Bruni) if she remembers him from the other day. She replies, oh yes, “You were with the pedantic gentleman.” The point is, I hope in my columns I don’t come off that way, since what I’m trying to do is express the idea that the further you go into art and art history (or music or literature), the greater the benefits are to one’s being. I can’t teach anyone how to experience a museum, but hope only to translate my own excitement to others with the idea that the more you put in, the more you get out of it.

By roundabout way of introducing this museum review, there is a funny scene in Woody Allen’s film comedy Midnight in Paris when, after having visited the Rodin Museum accompanied by a know-it-all art history buff, Owen Wilson returns there alone and asks the docent (Carla Bruni) if she remembers him from the other day. She replies, oh yes, “You were with the pedantic gentleman.” The point is, I hope in my columns I don’t come off that way, since what I’m trying to do is express the idea that the further you go into art and art history (or music or literature), the greater the benefits are to one’s being. I can’t teach anyone how to experience a museum, but hope only to translate my own excitement to others with the idea that the more you put in, the more you get out of it.

Speaking of Paris, I passed through Paris for just one day in July and was given a small window of time to go through the Musée national du Moyen Âge (National Museum of the Middle Ages, formerly known as the Cluny Museum). I’d visited the museum in 1991 and I’ve learned not to be surprised when things are completely different from how I remember them. The museum boasts an exceptional collection of works from the medieval period, including sculptures, architectural remnants from cathedrals and abbeys, tapestries, paintings, stained glass, and other items. I would doubt there is a better such inventory of the Middle Ages anywhere else in the world. About halfway through my visit, a most extraordinary feeling of contentment and satisfaction began to wash over me like a wave. Although many of the works on view center around Christian iconography, I am not a traditionally religious person (I was brought up Jewish and have devised my own spiritual philosophy). I realised that the museum acted as a sort of profound, wonderful aesthetic experience for me, a feeling akin to what one must feel when your team wins the World Series.

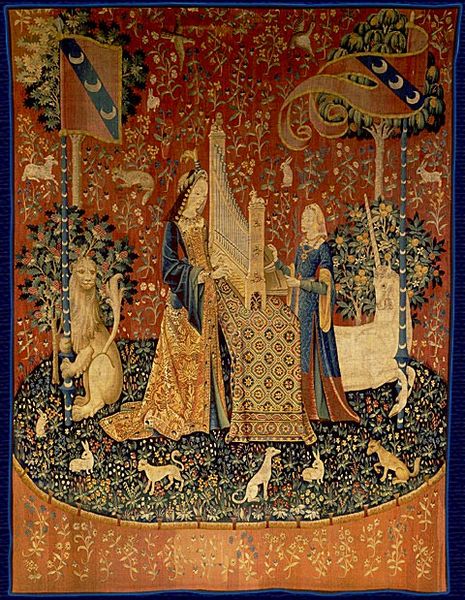

With the traditional museum experience of seeing paintings, visitors are drawn to individual painters and marvel at the genius of such widely viewed artists such as Van Gogh, Picasso, etc. But most pieces of medieval art are viewed as period pieces of “type,” and the majority were done by anonymous artisans, akin today to construction workers or carpenters and other fine craftsmen who make buildings or goods and whose identities are unknown to us. One is overwhelmed by the details of the colorful tapestries and majesty of the colossal heads of sculpted monarchs. The Renaissance ushered in the new period of the famous Master painter and his workshop. The late medieval paintings on view are mostly by unknown artists and the room displaying them had me nearly breathless in wonder. Other rooms that dazzled displayed themed tapestries, such as a “Unicorn” cycle, and another had several full-length sculptures, each on the level of a masterpiece.

The truly great art historians don’t just give overviews of art history, they interpret each work of art and, teach their readers how to actually view them, not only as visual stimuli, but each as a living, breathing presence with a vital, intellectual message. In particular, the late Erwin Panofsky and the late Michael Baxandall taught of the need to attempt to view a work of art in context of its historical and cultural circumstance. As one learns of the medieval period, one can’t escape its propensity for violence, superstition, and war, capped by plagues and pestilence. Wandering through the National Muse- um in Paris, one does sense all of that in the heavy-handed sculptures, which seem weighed down by their history and in the paintings that can be almost frightening in their stark depiction of the cruelties of Christian history and its myths. One is left to wonder if the artisans who made some of these fantastic pieces knew just how beautiful and ethereal they appear now, and that the works would be seen as such by future generations.

October 2013