Bernie Langs

Turner: Listen. I work for the CIA. I’m not a spy. I just read books. We read everything that’s published in the world and we– we feed the plots– dirty tricks, codes into a computer, and the computer…checks against actual CIA plans and operations. I look for leaks, new ideas. We read adventures and novels and…journals. I– I can– Who’d invent a job like that? I– Listen!- People are trying to kill me!

Kathy: Who?

Turner: I don’t know, but there’s a reason…

—-Dialogue from 3 Days of the Condor between Turner (Robert Redford) rand Kathy (Faye Dunaway)

Several groundbreaking American political espionage films emerged in the post-Senator McCarthy Communist “witch hunt” era of the 1950s portraying complex Cold War spy dramas. Seven Days in May (1964) follows the story of a decorated, crowd-pleasing military general secretly planning a coup d’etat to replace who he believes to be a spineless, weak-willed American President. Two other disturbing films at the time centered on brainwashing techniques of agents and assassins, The Ipcress File (1965) and The Manchurian Candidate (1962). Stepping back to the genre’s origins, Alfred Hitchcock’s cinematic genius as a filmmaker took off with his unique brand of suspenseful stories centered on the travails of a “wrong man (or woman)” mistakenly caught up in a web of nefarious intelligence operations. As early as the 1930s, Hitchcock presented movies such as the playfully tense The Lady Vanishes and the uniquely clever The 39 Steps. He would peak in this format in 1959 with Cary Grant’s portrayal of a suave, yet hapless advertising executive mistaken by enemies of America for a dangerously elusive spy in North by Northwest. Hitchcock was intensely interested in film as a study in the emotions of his endearing characters, with the central plotlines (dubbed by him as “The MacGuffin”) serving as backdrop for the maturation of his leading actors/actresses. In the 1960s, Hitchcock set films such as Torn Curtain and Topaz within a confining, humorless, danger-filled Cold War world, but neither effort came close to the high quality of his earlier work.

Several well-scripted films of the 1970s solidified this niche of intense focus on underhanded intelligence missions and programs, as accomplished directors presented ultra-serious stories abandoning traditional film fantasy for the civic-minded purpose of “educating” the audience in what they perceived as a new world order of political conspiracies. Moviegoers were served up suspenseful plot devices under the guise of tutorials about nation states that had evolved into pervasive ideological and economic protectorates eager to defend their fiefdoms at any cost. These campaigns fought out by political superpowers, as per the new wave of movies, were usually undertaken within the confines of a clandestine battleground and out of view of the general populace, whose role had receded to one of acceptable and necessary “collateral damage.” Although movies of this kind presented themselves as warnings of political and security agency overreach, the lesson taken home by audiences internationally helped create an underlying culture of paranoia and distrust of both business and government. The film industry discovered they could manipulate America’s surprisingly strong psychological need for baseless, unsound, unscientific explanation of reality using stories featuring maze-like alliances and betrayals unfolding within a place of graphic, choreographed violence.

Three movies in the 1970s are representative of the cool cinéma vérité, journalistic-like, exposé-stylized fictions depicting duplicitous schemes that ensnare Americans “in the know” as well as clueless bystanders, who stand in for the audience themselves. These dangers take many shapes and forms as they ruthlessly overpower and destroy all but the savviest individuals. American directors presented a world of hidden agendas, cloaked listening devices, and “Big Brother”-style around the clock video surveillance. The dire political yarn has dramatically shifted from Hitchcock’s heroic foibles of an everyman snared into unintended adventure, to films “exposing” the technical playbooks of governmental agencies supposedly held tightly under wraps and out of view of the sheep-like, docile public.

3 Days of the Condor (1975), The Parallax View (1974), and The Conversation (1974) put their characters in mortal danger, trapped by an ever-widening net of mistrust and double crossings. Alan J. Pakula directed Warren Beatty as a television journalist chasing down the truth of the killing of a presidential candidate in The Parallax View. Beatty desperately seeks to discover what is behind the politically motivated murder, and his reckless obsession culminates in the film’s horrific climax where his noble character is duped by an organized group of savvy villains, and he is caught with a rifle in his hands to be blamed for the assassination of another politician. Beatty, in that horrific moment of revelation to both audience and character, is left no opportunity to explain his side, as we watch in surprise his unjust murder. The bleak finale of Parallax serves as a knockout punch to a film already overloaded with angst. The brave reporter will be registered in the historical record of this fictional world as a crazed fanatic in the mold of Lee Harvey Oswald.

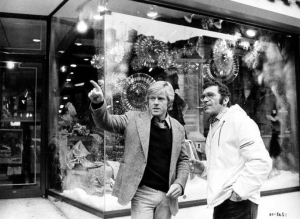

Francis Ford Coppola directed The Conversation and Sydney Pollack 3 Days of the Condor, both dramas aimed at giving their audiences a rare view from “the inside” of intelligence agencies and corporate surveillance services. Gene Hackman plays Harry Caul in The Conversation, a talented expert in the techniques of for-hire, surreptitious spying. Caul proudly figures out the near-impossible logistics of secretly taping a one-time conversation between a man and woman as they stroll around a park in San Francisco. Strategically placed microphones record each word as the couple glides in constant motion. Later in the movie, Caul becomes plagued by the unsettling intuition that he has been duped into acting as an accessory to a capital crime, and to his horror, discovers that the conversation was in fact a prelude to bloody murder. In the chilling closing sequence, Caul, the smartest man in the room in terms of hidden surveillance, is taunted by the sophisticated murderers that he himself will forever be under their watch, as we witness him tearing apart his living space down to the studs of the walls in a desperate attempt to locate the professionally concealed listening devices.

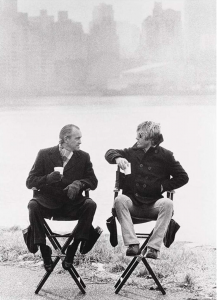

The mother and greatest of all paranoid spy movies of the 1970s is 3 Days of the Condor starring Robert Redford as a CIA wonk, Turner, targeted for elimination for reasons unknown to him.Turner’s job in intelligence is to read as broadly and voluminously as possible to intuit patterns indicative of activities that might threaten the interests of the United States. The film begins with a vague discussion between Turner and his superiors on whether or not his latest hypothesis has any “teeth” to it. Soon after, he leaves the office to buy morning snacks for his co-workers and returns to discover the bloody mess of death, which the audience has witnessed in his absence. A team of trained assassins gained entrance to the fronted CIA office space and, under the leadership of a cool-headed, patrician-aged killer with a foreign accent (portrayed with an odd elegance by the late Max von Sydow), shot the lot of them. This “man on the run” story entails dramatic twists and turns as Turner attempts to figure out who is behind the murders and why the perpetrators are still out to kill him. The interesting thing about Condor is the total lack of morality and decency within his own agency’s ranks and other players, outside of Turner’s and that of Kathy (Faye Dunaway), the woman enlisted at first against her will to help him. Towards the end of the film, Turner stands face to face in the night within the home of the agency’s higher-up, Atwood, who has been pulling the strings, having woken him up to confront him:

Turner: It was your network I turned up. Doing what? Doing what!!? What does operations care about a bunch of goddamn books? A book in Dutch! A book out of Venezuela!

Atwood: Wait,…!

Turner: Mystery stories in Arabic! What the hell is so important about [he stops dead still, then quietly notes] …Oil…fields. Oil. This whole damn thing was about oil…

Agency assassin von Sydow walks in at that very moment, but instead of shooting Turner as expected, eliminates the puppet master Atwood, since the coverup of the first round of elimination has gone recklessly too far. The danger exposed by the CIA analyst, Turner, in all its cloaked secrecy is not about nuclear codes or the plans for dangerous weapons, but the chase for what it is that makes governments behave like corporations, choosing to pull out all the stops if their consumer markets are threatened. Business is business in Condor, and heads receive bullets not from the gun of a crazed Oswald-type, but by expert “silencers” sanctioned by the CIA. This brand of storyline was unprecedented prior to the mid-1970s. As the movie draws to a close, Turner heads into the offices of The New York Times to expose the entire story. Though more hopeful than The Parallax View and The Conversation, it still leaves its audience with the message that this sort of intelligence agency behavior will continue to be carried out daily, ad infinitum into the foreseeable future. Whether or not Condor has presented an accurate depiction of CIA and other clandestine behavior is not considered as important to either the audience or the filmmaker. Ubiquitous conspiracies are now fed to the public on Facebook, Twitter, and various news outlets without the slightest attempt at fact-checking. A fatigued, battered public is far too often willing to believe anything it reads or hears, especially when presented in as few words or images as possible for the briefest of attention spans and displayed at the highest volume of feigned, overdramatic urgency. The tendency to believe a news bite false report in place of readily available facts and mundane truths is reminiscent of a sequence in the Marx Brothers movie comedy Duck Soup (1933). In an exchange between Chico Marx as Chicolini and Margaret Dumant as Mrs. Teasdale, Chicolini’s insistent that Teasdale is mistaken in what she absolutely knows as fact:

Teasdale: Your Excellency, I thought you left.

Chicolini: Oh no. I no leave.

Teasdale: But I saw you with my own eyes.

Chicolini: Well, who ya gonna believe me or your own eyes?

Duck Soup teaches a valuable lesson to those ignoring the truth in the face “alternative facts” and lies, and the barrage of misrepresentations is screamed at us with underhanded aplomb by a bevy of modern-day, humorless villains far less clever but no less dangerous than those presented in the cinematic fictions of Pakula, Coppola, and Pollack.