Sarah Baker

Photo Courtesy of Lavoz Magazine

Photo Courtesy of Lavoz Magazine

The past few weeks have highlighted the mental health crisis that our society is facing. Two high-profile and esteemed celebrities, fashion designer Kate Spade and Chef Anthony Bourdain, were found dead just days apart. These perplexing suicides remind us that success does not make one immune to unhappiness. Spade and Bourdain were far from alone in their struggles with mental health, but their deaths do stress a public health issue that has long been set aside. Suicide rates have risen in the past ten years, and this increase has not been addressed adequately by our society, our policies, or our institutions. It is time to destigmatize depression as a society, and especially here in our own circle at The Rockefeller University.

The realization that important figures in society face the same mental health challenges that many of us do has the ability to start a movement to combat this crisis. Spade and Bourdain gave the appearance of mental stability to the outside world, though people close to them admitted that they were both struggling with depression. These tragic suicides have resonated with people who have realized how they themselves have been grappling with anxiety and depression and has also motivated others to reach out to their loved ones, friends, and acquaintances who may also be struggling. The Twitter hashtag #MyStory has gone viral as many people, including celebrities, address their mental health struggles in a public forum.

Why have people suffered in silence for so long? And why do we still have so far to go in preventing these tragedies? The Center for Disease Control recently released a report indicating that 54% of people that have committed suicide in the past decade are people who were not known to be suffering from a mental illness like depression prior to their death. But many of these people were struggling with relationship or job problems, addiction, physical illnesses, or other immediate crises in their life. While people facing physical illness are often readily supported by friends and acquaintances, those suffering from mental illness usually feel that they must cope by themselves. Society regularly brushes off depression as mere sadness and suggests that, if someone just controls their thoughts, they will get over their feelings of misery.

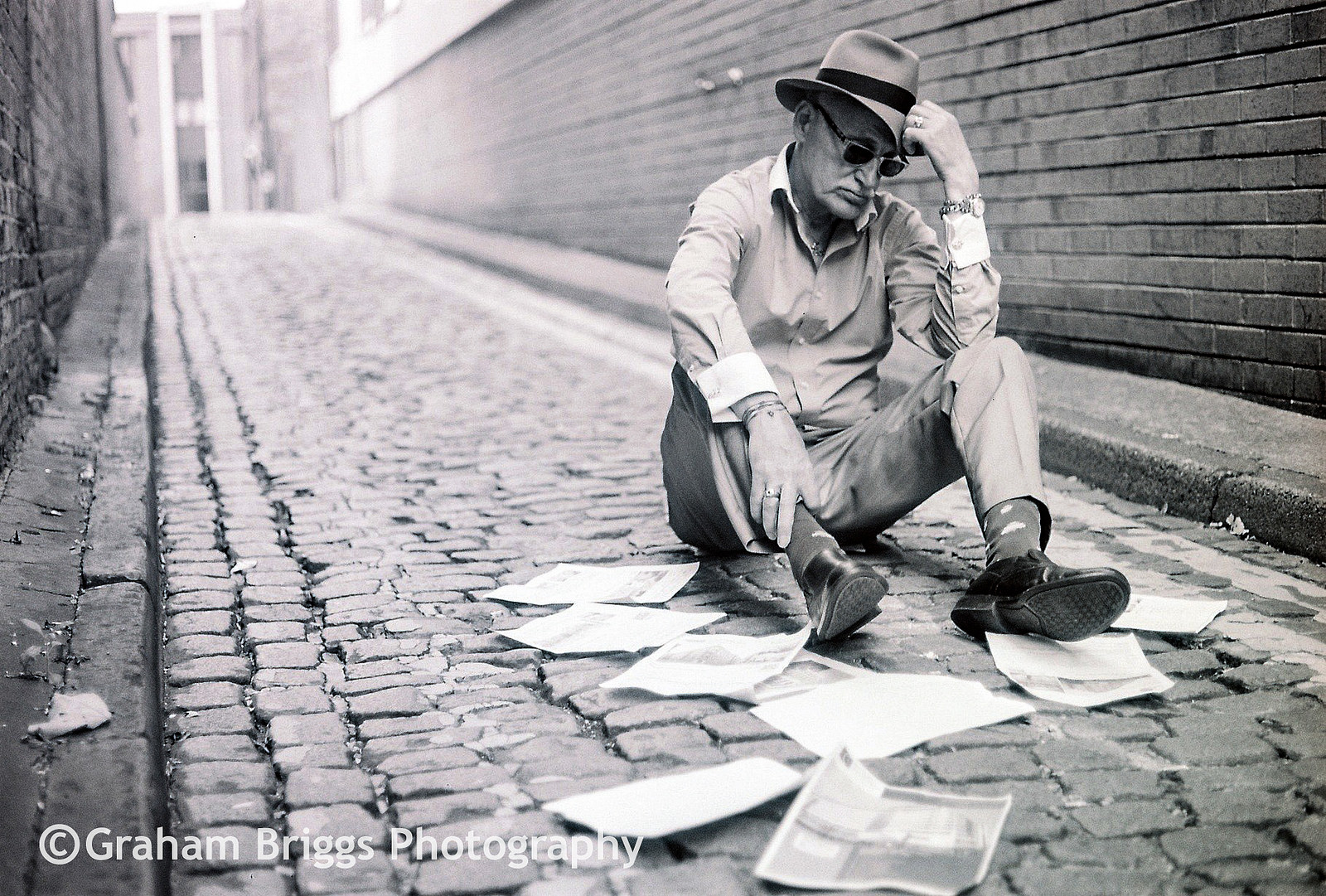

Photo Courtesy of Graham Briggs Photography

Photo Courtesy of Graham Briggs Photography

We need to make mental health a priority. People who suffer need access to affordable and accessible mental health services. Adding more barriers to treatment deters the people who need it the most who are already overwhelmed and who we should nurture rather than push aside. The Trump administration is trying to strike down a provision of the Affordable Care Act that prohibits insurance providers from discriminating on the basis of pre-existing conditions, which include any history of depression or anxiety. If this is passed, it could be devastating for people who need mental health services, making them essentially unaffordable. Empathy for those suffering from mental health conditions is also lacking. Depression and anxiety are not a choice—they are real conditions derived from physiological changes and our health system needs to address them as such. Pharmacological and behavioral therapies do make a difference when treatment is done properly.

In the type of academic environment that I work in, a shift in focus on mental health is paramount, because it has been shown time and time again that individuals in academia suffer greatly. A recent study published in Nature Biotechnology showed that graduate students experience depression and anxiety at rates six times higher than the general population. Sleep deprivation, stress, and the scarcity of tenure-track positions all play a role. Young trainees put a lot of pressure on themselves to perform well, and often face many internal mental challenges even though outwardly they may appear incredibly high-functioning. Females and non-gender conforming individuals suffer at higher levels than cis-males, and the relationship of the trainee to the principal investigator also contributes greatly to anxiety and depression, suggesting that mentorship is a crucial factor in student health.

Photo Courtesy of Mario Kociper

Photo Courtesy of Mario Kociper

I am now almost three years into my PhD and I fully understand how this environment can breed depression and anxiety. At breakfasts and lunches with prominent scientists hosted by the University where we have the chance to discuss career development, I have repeatedly heard that to make it to the top, you have to be tough. You have to battle to move up and not be affected too greatly by the challenges along the way. Although it is easy to suggest that resilience is the most important trait, I am often left with the feeling that success in academia is largely a solitary pursuit. Yet not everyone can just ignore an assault, or struggle on their own to come out on the other side stronger. Without a reliable network of mentors, friends, and other people you feel are facing the same things, it can be easy to get lost. Feelings of isolation and despair can be overwhelming. Yes, resilience is crucial, especially when failure is inherent in scientific research, but, as a community, we need to be better at developing this resilience in our trainees and showing them that they do not have to weather their struggles alone.

There is no one factor that leads to depression, anxiety, or suicide, but there are steps that we can take to cultivate mental health in our community. This must go further than sending out an e-mail once a year listing the mental health services available. Some things that can help are stress and mindfulness workshops as well as events that promote physical, mental, and social health among the trainee population. Students should feel as if they are able to talk to their mentors to gain advice about career opportunities, especially if they are interested in careers outside of academia, in order to alleviate some of the anxiety that comes with reaching post-graduation goals. At the University of Minnesota, students are required to fill out annual evaluations that address both research progress and also overall well-being. Principal investigators then look over these self-evaluations and discuss the reports with their mentees. Simply having this formal system in place has led to increased communication between mentors and mentees about expectations and continuing steps in the training process. In addition, and perhaps most importantly, we must cultivate a culture that makes individuals who are struggling with mental health feel as if they can speak up and ask for help rather than suffer alone in silence.

Recent celebrity suicides have shed light on mental health issues. Now society needs to step up and address this public health crisis. Change can be made at the community level, and institutions should assess how they can prevent similar tragedies. Graduate students are a particularly vulnerable population and because the system of graduate education is a known risk factor for anxiety and depression. It needs to be addressed head-on. We must shift towards more openness in the ability to discuss these issues. Our communities do have the choice to increase access to mental health services and to promote cultural change. At Rockefeller, a vibrant institution full of some of the best scientists in the world, no one should have to go it alone.

Rockefeller University Counseling and Mental Health Care Resources:

Confidential access to personal counseling and mental health care for all students is available through the Tri-institutional Employee Assistance Program Consortium (EAPC). If your life seems to be getting harder to deal with, do not hesitate to contact EAPC. In an emergency, they are available at (212) 746-5890, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Employee Assistance Program

409 East 60th Street, Rm. 3-305 (between York and 1st Ave.)

Regular hours are 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday

Phone 212-746-5890

EAPC provides short-term counseling to members of the Rockefeller, Cornell, NY Hospital, Hospital for Special Surgery, and Sloan-Kettering community—students, their families and significant others included. The service is provided at no charge to individuals.

EAPC is a confidential referral service geared towards short-term problems-solving for any personal problem you may have—depression, loneliness, relationship or family issues, substance abuse, legal or financial problems, child care services—anything. The social workers on staff will first help you evaluate what your situation is, and then discuss all possible avenues for resolving the situation to your satisfaction. There is no long-term counseling offered at EAPC, but they can set you up with counseling if it is needed. Referrals for counseling include psychiatrists, psychologists, psychotherapists of other types, and social workers. A few visits to EAPC (maybe only one!) may be all that is necessary for you. Appointments may be made during normal business hours and there is a 24-hour emergency cover given through the number given above.

On site counseling services are also available. Dr. Daniel Knoepflmacher, M.D. is available two days a week to meet privately with members of the RU community. If interested in scheduling a confidential appointment, please contact Occupational Health Services at (212) 327-8414.

For those who prefer a more holistic approach to mental health, Rockefeller Wellness has got you covered:

Mindfulness Practices for Stress Reduction

Stress is one of the biggest contributors to poor health. Its effects can cause physical illness, damage relationships, and negatively impact work performance. Mindfulness meditation is a means to reduce stress, boost the immune system, improve attention, and promote well-being. Try Sitting Meditation or the Body Scan on your own with a guided audio clip of Dr. Patricia Bloom.

Patricia A. Bloom, MD is a Clinical Associate Professor of Geriatrics at the Icahn Medical School of Mount Sinai and the past Director of Integrative Health for the Martha Stewart Center for Living at the Mount Sinai Medical Center. Her main interests include the promotion of healthy aging, integrative health, stress reduction and Mind Body Medicine. She teaches meditation and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for patients and conducts stress reduction workshops for professional and workplace groups. Dr. Bloom has been listed as one of New York Magazine’s “Best Doctors” for 15 years. In 2012 she was honored by the New York City Zen Center for Contemplative Care for her work advancing integrative medicine in academic settings.

Mindfulness Resources in and around New York City.

Editor’s Note: Access to the URLs in the above Rockefeller Wellness section is restricted to those within the Rockefeller community.

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention’s Guide:

Warning Signs of Suicide:

- Talking about wanting to die

- Looking for a way to kill oneself

- Talking about feeling hopeless or having no purpose

- Talking about feeling trapped or in unbearable pain

- Talking about being a burden to others

- Increasing the use of alcohol or drugs

- Acting anxious, agitated or recklessly

- Sleeping too little or too much

- Withdrawing or feeling isolated

- Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge

- Displaying extreme mood swings

The more of these signs a person shows, the greater the risk. Warning signs are associated with suicide but may not be what causes a suicide.

If someone you know exhibits warning signs of suicide:

- Do not leave the person alone

- Remove any firearms, alcohol, drugs or sharp objects that could be used in a suicide attempt

- Call the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255)

- Take the person to an emergency room or seek help from a medical or mental health professional