Celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Beggars Banquet by The Rolling Stones

Bernie Langs

In December of 1968 The Rolling Stones released Beggars Banquet just months before they would be introduced as “the greatest rock and roll band in the world.” The record, which features tunes by the songwriting team of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards at the very peak of their creativity, has a consistent, unified sound. Richards’ guitar work on Beggars ranges from nuanced and subtle to in-your-face, airplane engine electric power chords, ringing out and enveloping Jagger’s vocals in a cocoon of creative textures. Charlie Watts on drums and Bill Wyman on bass anchor all of the music with exactitude and precision. The band’s fifth member, Brian Jones, was fading away at the time of recording into an introverted state of confusion and a paranoid drugged out haze. Jones only contributed here and there, his last gasp of what he did best as a musician, putting the cherry atop the sweet sundae of the Stones’ tracks. It would be his final album as a Stone, as he was asked to leave after the record was completed so the group could bring in virtuoso guitarist Mick Taylor. Just a month after exiting the band, Jones died, drowning in his swimming pool.

Beggars Banquet was the first Stones album produced in the studio by the late Jimmy Miller. Miller would go on to work with The Stones on their finest albums, including Sticky Fingers and Exile on Main Street. Glyn Johns served as the studio engineer on Banquet and Nicky Hopkins provided piano for the band, shining on these tracks with his individual style. The late Hopkins may have been the greatest keyboardist who served as a hired hand for any major popular music band.

I was eleven years old when Beggars Banquet was released in America. My siblings and friends all knew that this record was something special, appearing a year after The Beatles released their genius LP, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Nothing on Beggars was similar to Pepper’s. The compositions penned by Jagger and Richards remained rooted in the chord structures of traditional blues and also continued the Stones’ extrapolations on Chuck Berry’s “1-4-5” structure of early rock and roll composition, a pattern also derived from the blues. Lennon and McCartney’s songs on Pepper’s dazzle in experimental melodic complexity amid George Martin’s nuanced production. Martin and The Beatles would selectively celebrate their tracks with orchestral strings and woodwinds when the moment called for it. In contrast, the Stones stayed minimalistic on their records and could easily move from studio to stage with their tunes centered around two guitars, bass, drums, and piano, with small horns thrown in at times for variety.

Beggars kicks off with the infamous “Sympathy for the Devil” which was viewed in 1968 as reflective of the Stones’ image of danger and dark mystery. Even in my youth, however, I was intrigued by the serious nature of the lyrics and how deeply poetic they were in contrast to a lot of throw-away songs at the time. As Jagger steps into the guise of Lucifer, he’s more Oscar Wilde’s horrific gentleman Dorian Gray than a horror flick notion of the Devil. The character takes the listener on a tour of mankind’s violent history and sings with intensity as he describes his role both as observer and bloody instigator. The song’s exotic descriptions include gems such as “I lay traps for troubadours who get killed before they reach Bombay” and “I watched in glee as you kings and queens fought for ten decades for the gods they made,” which may be the only reference in pop and rock music to The Hundred Years’ War. Lucifer is a “beggar” who demands sympathy for what he’s watched us do and what he has had to endure. Yet he also threatens that “if you meet me have some courtesy, have some sympathy, have some taste; use all your well-learned politeness, or I’ll lay your soul to waste.”

Jean-Luc Godard, the French New Wave director, filmed the Stones recording “Sympathy” and put some of the footage in his movie “Sympathy for the Devil.” I find that movie ridiculous and unwatchable and wish someone would extract the footage of the band, add moments that didn’t make the final cut, and release it on its own (note that director Peter Jackson is currently taking the best parts of footage of The Beatles’ mess of a 1970 documentary “Let It Be” and adding many new scenes of them playing that were left on the cutting room floor). Godard captures how the band began with Mick Jagger strumming “Sympathy” on a guitar and how after some standard arrangements, the piece shifts to the heavy percussive Latin background sound, which is heard on the album. The congas and drums conjure the devil like Shakespeare’s witches brewing evil tidings from a boiling kettle. The song builds to a frenzy and fades away with the singer’s echoing falsetto cries as Lucifer spirals downwards to hell—the band plays furiously amid Richard’s sharp lead guitar work knifing through the mix. Lyrically, the words have more in common with England’s grand poetic tradition than the good vibrations and flower power anthems spilling out on the radio at the time. If Bob Dylan can win the Nobel Prize in literature for his groundbreaking lyrics, Jagger and Richards surely qualify as Britain’s Poet Laureates.

Beggars has fabulous moments of acoustic guitar-centered songs. After “Sympathy” fades out, the next tune is “No Expectations,” a Jagger and Richards song that mirrors the classic “Love in Vain” by American bluesman Robert Johnson. The Stones would record “Love in Vain” for their next album, Let it Bleed and while Johnson’s tune is about unrequited love and features images of trains leaving the station with one’s lost lover, the narrator of “No Expectations” is broken-hearted and requests in the opening lines, “Take me the station and put me on a train, I’ve got no expectation to pass through here again” and ends with a similar plea to be sent off far away in an airplane. The song’s narrator describes the fleeting nature of the love he’s lost, “like the water, splashing on a stone” and notes, “Our love is like our music—it is here and then it’s gone.” Brian Jones plays a wicked slide acoustic guitar, which resolves on an “open” E chord that Keith Richards must have been awed by, even through his anger with Jones’ continual drugged out confusion.

The best acoustic performance on Beggars is, “Prodigal Son,” written by Robert Wilkins, a reverend who recorded in the 1920s and 1930s. I’m not certain how old I was when I realized that the story of the song is Biblical, the famous tale of the arrogant youth who leaves home to find the world a harsh, punishing place and later crawling back to his father for forgiveness. Jagger singing affects a Southern, African-American spiritualist tone and Richards’ acoustic chords and lead flourishes are passionate and heartfelt. After Jagger’s last line, “My son was lost but now he is found” you can hear Richards give a guttural cry of “Hey!” as he brings it on home. One may venture that Mick and Keith would be absolutely content each day to sit on a porch in Mississippi in the summer sun, playing guitars and singing songs while swigging moonshine from a jug.

The rock songs on Beggars are fantastic, especially “Parachute Woman” and “Stray Cat Blues.” “Stray Cat Blues” in particular is an example of the Stones’ swaggering sexuality. When I was teaching myself guitar as a teenager, I would tune up to Beggars to play along with the album, and the rhythmic intensity of “Parachute Woman” was difficult to master. When I finally got it down, it was almost as if the guitar took over in the song for itself, and the intensity of the trancing repeating riffs brought me to a plane of surprising joy and newfound release. I could never truly master Keith’s leading stabs in “Stray Cat Blues” but Jimmy Page would give them homage on Led Zeppelin’s final album, “In Through the Out Door”.

The greatest masterpiece song on Beggars is “Street Fighting Man.” It is a slice of English history in living color, summing up the frustration of being a young man with energy and new ideas in 1960s London. It speaks of revolution, revelation, rebellion, and resignation all in one set of lyrics. Even if youth should run rampant through the city streets and “kill the King” they will ultimately be reduced to nothing more than bit players in a culturally limited rock and roll band. The sound of “Street Fighting Man” is the most complex in terms of instrumentation on Beggars. Charlie Watts and Keith Richards recorded their initial drums and acoustic guitars on a cassette recorder and Jimmy Miller manipulated that sound to abstract perfection. Additional guitars, percussion, and piano were added later and Brian Jones contributed well-placed drones on a sitar. Jaggers’ vocals are menacing, multi-tracked, and startlingly direct. I’ve listened to the song for fifty years and it is fresh on each hearing.

Beggars closes out with a beautiful song “Salt of the Earth,” an ode to the working class men and women of Great Britain. At the same time, in the song’s middle break Jagger admits that while on stage performing, the crowd is nothing but a “swirling mass of grays and blacks and whites” that don’t seem real to him and are actually “strange” in his eyes. The song hits a galloping peak and they give pianist Nicky Hopkins the honor of having it fade out to his manic right hand banging out a set of rapid chords.

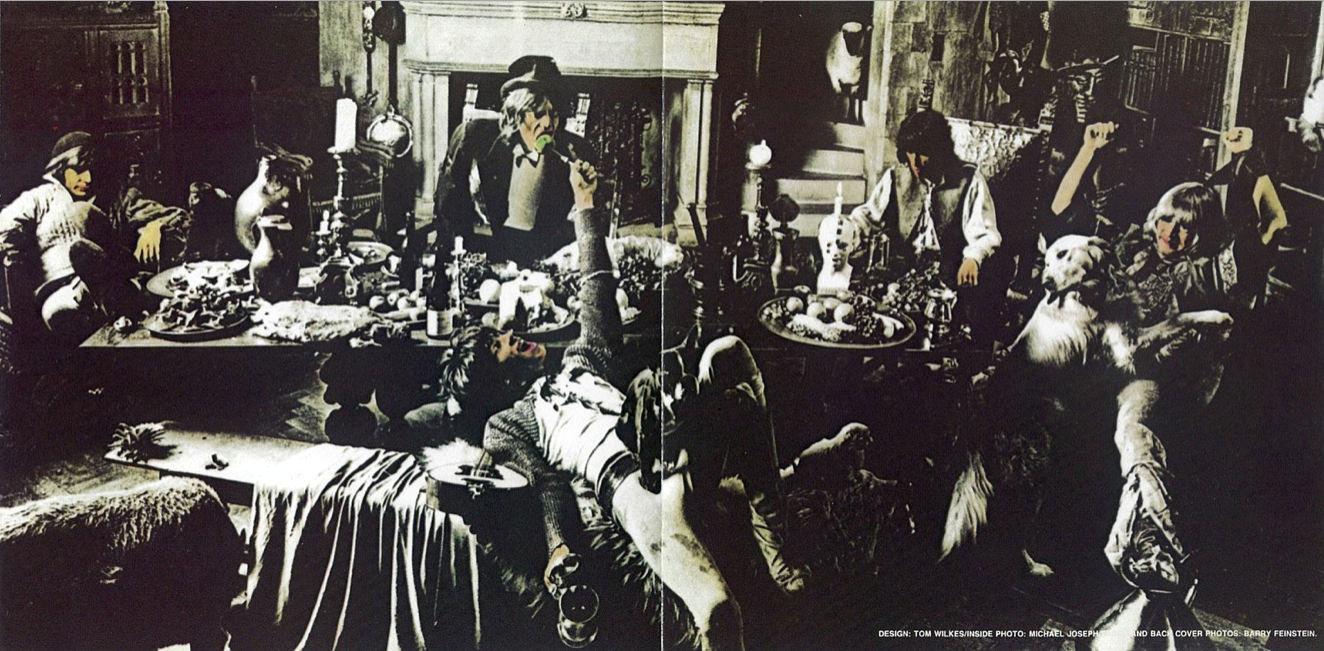

The album’s release was delayed in 1968 because the record companies in America and Britain balked at the LP’s cover art of a dirty public bathroom with graffiti about the Stones and the songs on Beggars. It was eventually released with a white cover and a mock invitation to the banquet. The inner sleeve, however, boasts a black and white photo with shades of muted colors of the Stones celebrating like peasants who have invaded the King’s table in the Dark Ages. It may be the greatest match of image and personality in a band in the history of rock music, a fitting idea for an incredible piece of music.