Bernie Langs

David Bowie’s music always showcased complex arrangements, alongside lyrics reflecting the turmoil of our world. To learn more about Bowie and his music, I contacted musicians and producers who had worked with him during his productive recording and touring years (2002-2004) hoping to land an interview.

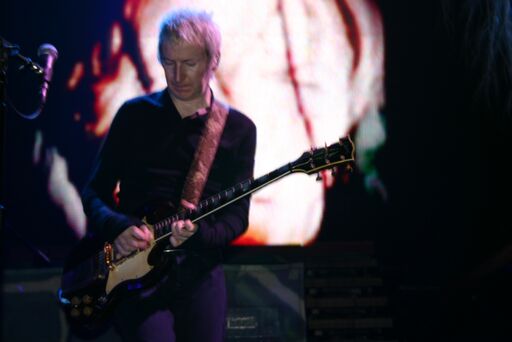

Guitarist Gerry Leonard, who worked with Bowie at that time, amiably agreed to speak with me. Leonard appears in YouTube videos of several of Bowie’s tours and in documentary movies about Bowie’s late career.

Leonard hails from Dublin and studied classical guitar at the Municipal College of Music. He became interested in the harmonic possibilities of the electric guitar and developed an encyclopedic knowledge of equipment for creating original ambient sounds using complex machinery. His solo career centers on his work with his band, Spooky Ghost. Leonard recently toured with rock artist Suzanne Vega and with Rufus Wainwright. He has also worked with performers such as Laurie Anderson, Cyndi Lauper, and Avril Lavigne.

Leonard’s work with David Bowie is featured on the albums Heathen, Reality, and The Next Day, lending ambient space that gels seamlessly with Bowie’s musical vision. His guitar sound allowed Bowie to expand and perfect his musical statements. Leonard also acted as Musical Director for Bowie’s Reality tour.

Gerry Leonard (r.) and Gale Ann Dorsey (center) with David Bowie. All photos courtesy of Spooky Ghost: The Official site of Gerry Leonard https://gerryleonardspookyghost.com.

I interviewed Leonard on the phone and met him briefly in December. Here is an edited version of our conversation:

Bernie Langs: Artists such as U2 and Sinead O’Connor continue to reflect traditions of Irish music. Your work with “Bowsie” and Susan McKeown reflects that. Do you approach this as a responsibility, a need to continue this tradition?

Gerry Leonard: It is in a sense [a responsibility]. Music and writing and literature, poetry, all of those things have very rich traditions in Ireland because Ireland was essentially a pretty poor peasant country—all of the entertainment and all of the stories in the late night get-togethers with people making their own entertainment, and making it their own, passing on their own heritage, through story and songs. That’s very much alive in the arts culture and always has been. And I think you see that with Sinead O’Connor and U2—we all come from the same water in a sense that the stuff was around.

However, when I started picking up the guitar, I was really interested in [the British TV music show] Top of the Pops. We’d watch the bands and then I’d get together with my friends—we had a little band, and then we’d try and work out these songs. We then got into a little bit of progressive rock and then punk rock and new wave hit for me in the mid-late ‘70s. And it was such a profound shift in terms of the role of the guitar in music, the type of bands.

I’ve always had a huge respect for the Irish traditional music. Susan McKeown, in regard to the “Bowsie” project, she came to me and I was already doing my more ambient, guitar-scape kind of music, and we had this idea to take some of these traditional Irish songs that she had learned in an oral tradition. She’d gone and traveled and met the person and they taught her the song. She visited people and learned the song from somebody, which is the way it needs to be done.

BL: You’re known for your ambient sound and guitar loops and creating that kind of atmosphere. What drew you to that?

GL: I really love music and it’s always resonated with me on a deep level. Emotionally, I love listening to music and playing music and the raw power of rock and roll. But I also love more complicated things [including] some of the modern classical composers. I really like what [recording artist/record producer] Brian Eno does for instance, with space. I’ve always taught that through the use of some basic guitar pedal ideas, like echo, reverb, and distortion, you can start to change the harmonic characteristics of the sound and the length of the sound. Cathedrals, for instance, you go in there and you play a note and it does all that reverberation. Something changes in the sound and it becomes enriched by its surroundings.

When I play in an ambient way, I really recreate those kinds of atmospheres. It’s an environment, a flavor, and a color. When I teach, everybody’s focusing on the pedal and so forth, but there are many variations on the machines that do those things in different ways and some in really beautiful complex ways, but what goes in is important too, and that’s for the harmony and the music and the musical idea. I practice two things: like the way an athlete would practice, it’s a muscular thing, being in touch with your instrument, and then I practice harmonically, trying to understand the different keys, different voicings, and be more fluent in those things. Or in the studio, I can quickly analyze the harmonic sense of the song and where I see these shapes and colors in the song I can try and accentuate those with the ambient thing or with a line that’s got a certain tonal quality to it, which brings more color to the picture of all the elements that are really important.

If you think about a quality of a David Bowie song, for instance, he always had a kickass rhythm section and he always loved guitar and stuff, but there’s also room for a coloration or something a little more extreme in there and he enjoyed that boldness. Getting to play with David was a great culmination of a lot of those things for me. I think of recording as a snapshot, and it can be very static, but it can also be really interesting and mysterious. That is when it gets interesting to me, when you get this kind of lightning in a bottle where you’re getting something extra. It’s a constant quest.

BL: It’s amazing that Bowie recognized that he could use your technique for his work.

GL: It really was. Part of being in New York was about establishing a foothold for yourself. I’d been playing whenever possible, just learning my craft, and using New York as a filter to figure out what’s your strength, what’s not your strength, especially in regard to ambient guitar, figuring out a way to make it happen in the room live. I’d been working on all those things and then the call came through from my friend Mark Plati. Mark was working with David and asked me to do a track, and one thing led to another.

It was a very, very proud moment to get the call from David to be involved with him. He’s such an icon, and as a guitar player, it’s such a great legacy to be involved in, to be one of the guitar players. Even if it was in his later career, just to be able to play all that stuff with the guy who was there and wrote it. And he was a great inspiration to be around playing that stuff. It brought such a level of authenticity to it, and his very being—being around David you got that guru-like quality about him. It was tremendously exciting and a great honor, and it’s one of those ones where you really have to pinch yourself and go, “did this really happen?”

BL: When you were with Bowie, was there always an awareness of who he was?

GL: I realized quickly that when you’re with David, people start seeking you out with [ulterior] motives. You’re sitting in a hotel lobby waiting, and somebody comes up and goes, “Hey Gerry, do you want something to drink?” And I’m like, “Who is this person?” So you realize you kind of have to put up a wall around that because people want to get to David because he really is that person—he’s a rock star, but he’s touched so many people and changed so many people’s lives, and people have this real adulation for him.

The nice thing about working with David is he never wanted that; he didn’t want anybody sucking up to him. He wanted to be able to just be himself and he wanted you to be yourself. So that was always nice and refreshing to be around. But you have to put up a little bit of a wall around him because people, they changed their nature towards you.

BL: When you were with him alone or with him and the band, could you ever let go of who he was?

GL: Yeah, we did—I think we did. We had a lot of laughs. He was very good at kind of breaking that stuff down. You would get to a place where you were not self-conscious and that’s what you want. You want the truth in yourself and in your nature and in the way you responded to things, and you don’t want to be a deer in the headlights and freeze up. He wants you there to be part of a creative solution. We would pretty quickly, especially when we were working on music, get to a place where it was very relaxed. I’d been with him in social situations, too, and when we were together it would be really easy. Sometimes we’d go out to an art museum or something, and people would sidle up to me and go, “Is that David Bowie?” and I’m like, “Yes, it is, but you probably should just leave him alone. Because he’s there and just wants to look at the art.”

BL: I’ve watched videos of you discussing how “Loving the Alien” came to be performed with just you and Bowie. How did you feel alone, just you two, performing that song onstage?

GL: I literally got a call on a Tuesday. It was very David, where he’d obviously come up with this idea where he was like, “I want to do this song, I want to do a stripped-down version of it,” and he called me and told me, “Rehearsals are on Friday, are you up for it?” And I was like, “Yes, of course, I’m up for it,” and I remember putting down the phone and going to listen to the song and having that moment of panic, “What do we do here?” I worked on it and came up with that little [guitar loop] line, changed the key, and worked out a version on the guitar. When I got there on Friday, we did a couple of songs [in rehearsal], Tony Visconti had a string quartet and we were doing the other song and I was playing on those and everybody left and it was me and David, and he’s like, “Did you get to look at ‘Loving the Alien’?” and I played this loop to demonstrate and I start playing with it and he comes in singing and I keep playing and he keeps singing—we do the whole song. And he said, “Great, we’ll do that tomorrow night.”

Then that was that. It was like one of those things where I guess I got it right, but it was his idea, his song, and his idea to do it in this way. I brought my thing to it. He liked it. We did it. He liked it so much for me to continue to do it and it framed the song. It would be fair to say that we didn’t overthink it, but I also worked with David a few times prior, so I knew that I had to come up with something that stood on its own. I’m really proud that we got to do that. I’m very proud of the arrangement, and I love that he liked it. So, it was a nice moment where our two worlds met.

BL: It seems that Bowie recognized what all of you were doing for his music, using, for example, bassist and vocalist Gail Ann Dorsey as a foil while performing the songs and joking with the audience.

GL: Well exactly. David loved the personalities and he chose people as role players. Mike Garson [Bowie’s long-time keyboardist] would say he was like a casting director when it came to this and he did celebrate the musicians. He was very generous in those ways. And he was very comfortable in his own skin and he was able to share the spotlight in the sense, to give Gail a solo—and he always gave people their due.

BL: On the Reality album, I sense the perfection in the studio that began with Station to Station. And the social philosophy that began with Low. When you were working in the studio on Reality and Heathen, were you thinking of it that way?

GL: He definitely heard a lot of those philosophies going around, you could tell, in terms of the songs. I love what he did with Heathen. He took a real shift—he was going to do this record, essentially his reworked songs that he had over the years, and then suddenly he shut down that project and went and did Heathen. It was almost like he went off and wrote a novel or a prose thing. And I love that about it.

David was such an avid reader. He was always a searcher. You could tell. You’d come in, and if you hadn’t seen him in a while, he was always full of these stories or facts or things that he was interested in, whether it was art, sculpture, TV shows, whatever was going on. He really liked to stay in touch with a lot of things that were current, whether it’s music or comedy or TV or film, but he was always reading all kinds of stuff. And when he did the Next Day record and the Black Star record [Bowie’s final album] he was really into his books and those stories are seeping into his work. It’s a classic situation where David always got this insatiable thirst for art and then he had this way of taking what really inspired him from that stuff and somehow working it into his records and his music, and I think that happened all the way along. He just had this uncanny knack. I think when you got two records like Heathen and Reality it was just a more evolved, or more grownup version of it.

You were aware that these things were going on. Often though, working with David, you didn’t get the full picture until later because he would [only] have some lyrics done. He’d generally have a melody and a sense of what or where he wanted the song to go. But he was always open for you to put your two cents in. And sometimes you put something in there, and it would make it turn for everybody.

BL: When I saw Bowie in New York in 1978, there was no rock star thing going on with him. I was amazed he would stand back in the background just enjoying the band at times during solos.

GL: That’s classic Bowie. He was really good at reading people, reading situations. He had an instinct for that. I think he’s a huge music fan too, with other artists, and he had a real sense of how to write a song. If you take something like Heroes, he’s already reinvented himself a few times. And now he’s with Visconti, and he’s coming to the table with all these fresh ideas. It made such a potent thing, and it knocked all our socks off.

BL: When Bowie died, my friends and I were heartbroken. It’s so rare that a public figure’s life is so roundly applauded for his life in the media on passing. But for you, this is your friend, bandmate, and creative partner, a different level of grief.

GL: It is. It’s still hard to believe that he’s not with us. I was used to long periods where I wouldn’t see David, or didn’t speak with him, so it wasn’t unusual to be without him for a while, but at the same time, to realize that you’re never going to have those moments again is really, really sad. You have a feeling of the things that you should have said, you could have said, opportunities that were missed, just on a personal level, you think, “Oh God, why didn’t I say this? Or do this or ask him this?” It’s ongoing. At the same time, I know he would want us to just do our music and be the best that we can be. He was always really encouraging. When I was with Spooky Ghost, and I would do some shows on the road, he would come out to them every now and again, just to hang out. He was super supportive. So you temper it with that. We miss him.

BL: One of my friends once said, “There will be all the pop songs that nobody’s going to remember in the years ahead. And at that time, they are still going to be studying David Bowie.”

GL: Well, I think he would be happy to hear that. I don’t think he was made in that way, but he was a searcher, and he was not interested in resting on his laurels. That’s what is really rich about this whole scene of David Bowie, that there’s plenty to go on, and the archeological dig can continue for some time. The guy operated on a lot of different levels, and yet he was able to write and speak to the multitude. He had that gift, whether in Changes or in Heroes, or any of these iconic songs, he was able to capture what we all thought, felt, and wished for. That’s what’s beautiful about it. It was always contemporary, and it was always written for the people. It wasn’t written for some kind of elite. A unique gift. I miss him terribly.

People come up and tell me that all the time, especially when going to do these Bowie celebration gigs, and that’s all they want to talk about, their experience how David moved them, how he changed them. It’s really remarkable. It’s also hopeful. I feel like as part of the legacy with David, part of our duty is to keep his work alive. I feel very lucky to have worked with him, he was the one that really moved people, and everybody’s looking to get a little closer to that.

Thanks to Victor Cisneros and Erin Henegan for technical assistance in recording and transcribing this interview. [Edited for clarity and length.]