My Thoughts On Two Documentaries: Long Strange Trip (Amazon Studios, 2017) and Eric Clapton: Life in 12 Bars (2017 film; released on Showtime Network in February 2018 for television)

Bernie Langs

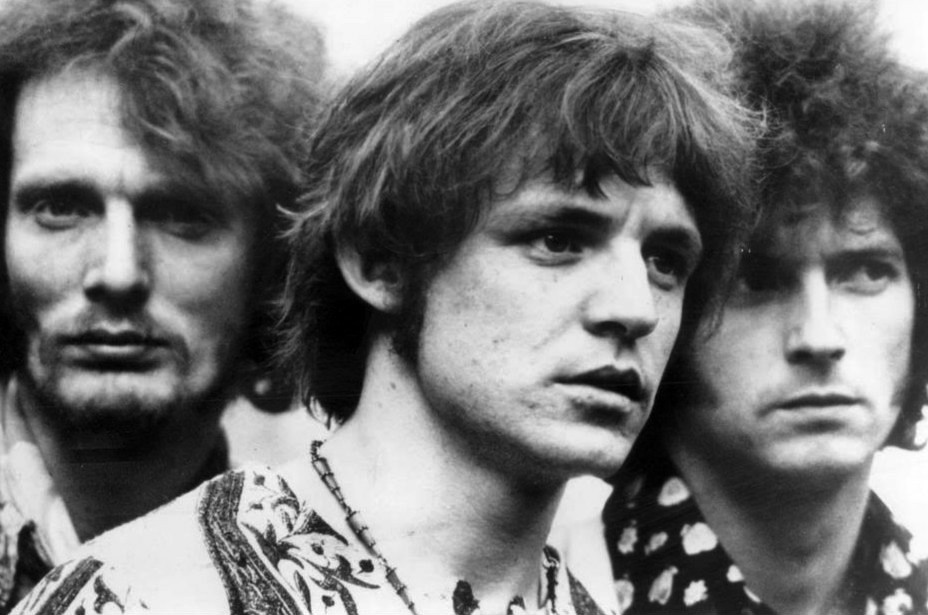

Cream in the 1960s, (from left to right) Ginger Baker, Jack Bruce and Eric Clapton (source: Wikipedia)

Promotional poster for Long Strange Trip (Amazon Video)

Two recent documentaries, one on the Grateful Dead and the other about Eric Clapton, offer fantastic insights into two of the most talented and powerful musical forces that arose in the 1960s. All of the surviving members of the Dead are interviewed at length in the Amazon Studios-produced the 6-part, Long Strange Trip directed by Amir Bar-Lev. Eric Clapton cooperated with director Lili Fini Zanuck in the making of the story of his life by giving voiceover narration to archival film footage, music, and documents from his long career as a premier English blues and rock guitarist. Both documentaries offer incredible journeys into the music and lives of those involved, including candid appraisals of some of their darker moments. In particular, the living-on-the-edge life of the Grateful Dead’s late leader Jerry Garcia (1942-1995), his tragic death, and the terrible self-abusive states of addiction suffered by Clapton.

I saw the Grateful Dead three times between 1978 and 1980. During that period, I would often play along at home or college on guitar with Dead albums, where I learned to listen carefully to the other players and respect the unity of the whole sound rather than standing out as a soloist or “stepping” on another musician’s phrase. The Grateful Dead were known for playing as a unit and for being uncannily of one mind during their complicated and experimental live performances. When I joined a band in 1979, I took this lesson to heart as I played with my fellow bandmates. In the documentary, bassist Phil Lesh, drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann, and rhythm guitarist and vocalist Bob Weir delight in discussing the magic of playing and jamming live and how the audience would be taken along with them on their journey.

As the Dead’s audience grew, it made a transition from arena performances to stadium venues. These shows attracted a large number of people who would arrive without tickets, many in hope of gaining free entry by slipping through fences or gates. Others would set up booths to sell unauthorized merchandise and there were those who abusively drank alcohol or ingested drugs leading to erratic or often dangerous behavior. The members of the Dead grew alarmed as violence became a regular feature in stadium parking lots, at times to the point of loss of life. Lesh, Weir, Hart and Kreutzmann took to recording public service announcements with forceful messages that only ticket holders were welcome and that the circus-like atmosphere that had been created was not in the true spirit of what the band stood for.

The surviving members of the Dead appear to have emerged in excellent mental shape after years of substance abuse and come across as sharp, insightful and articulate in the film’s interviews. Lesh gives a detailed account of how virtuoso guitarist Garcia deteriorated from heroin use in his final years. He notes that even if the band had stopped touring as an intervention, Garcia would have likely just gone out on the road with his solo band and met with the same sad end.

The musical soundtrack of Long Strange Trip confirms that the Grateful Dead’s performances remain beautifully textured and vital, with each member playing lines of melody that unite seamlessly into a magical whole for a refined essence.

Eric Clapton: Life in 12 Bars is a completely different tale of self-destructive behavior of a guitar magician. The documentary runs just over two hours and is an extremely painful two hours at that.

I have seen Clapton perform many times, but not in the past 25 years. I have great memories of a concert in the 1980s at a small club in Manhattan and of an outdoor festival in 1978 at an aerodrome field outside of London. I became aware of the talented blues player in 1968 when my brother mixed up our daily album selections with records by a far out band from England called Cream. I was 11 years old and records such as Wheels of Fire completely changed my understanding about music. Cream’s extended jams pounded at a breakneck pace, with Mr. Clapton soloing at blistering speed amid the complex, jazz-inspired drumming of Ginger Baker and the wandering, fuzzed basslines of Jack Bruce. I believe that this was Mr. Clapton’s peak period which was matched in 2005 at Cream’s reunion concerts at the Royal Albert Hall and Madison Square Garden where the wisdom of all of his playing years coalesced.

The band’s final album, Goodbye, was a farewell to their fans offering a selection of live recordings and studio songs. The opening number is a live version of a fast-paced blues song that was one of their signature numbers, “I’m So Glad.” The song has Clapton tearing off what I believe to be the finest guitar solo in all of rock music, performed with screaming passion and intensity that never flags.

The Cream years were rough on Clapton, having already emerged as a blues star and given the nickname “God” by his London fans. Whereas the Dead welcomed widespread fame, Clapton didn’t care in the least about stardom. He wanted to perfect his craft and was on a mission to educate the world about the unrecognized African American pioneers of the blues genre. The late Muddy Waters and B.B. King appear in the documentary speaking fondly of the unexpected popularity of their music after Clapton had worked tirelessly to promote it.

In one film segment from the 1960s, Mr. Clapton plays some riffs for an interviewer and notes how he can be “aggressive” as he slashes into a searing lead. This particular guitar tone had been a Cream staple sound during live performances, for example, in “Deserted Cities of the Heart”. Later in the film, as we watch Mr. Clapton descend into years of alcoholism, he goes on record at the time as hoping his life would end, in order to remedy his suffering. In one interview, his eyes barely open, he bitterly wishes that Cream had never existed and says that he loathed, once again, his “aggressive” tone and playing from that time.

Clapton describes in detail how his problems stem from his troubled family history, having grown up believing his grandmother and step-grandfather were his parents only to learn his older sister was his mother and that his father was nowhere in the picture. His mother went off to have another family, and when he finally does meet with her, she acts terribly, scarring him for life and pushing him into the solitude of obsessive practice, which made for a genius guitarist. Equally tragic is how much Clapton enjoyed the positive energy and friendship of fellow blues genius Jimi Hendrix and how much the overdose death of Hendrix left him feeling isolated and alone with his talents and musical insights.

I had known of Clapton’s heroin addiction, which ceased in the 1970s, and that he’d gone into alcohol rehab years later. I had not known until 12 Bars that his drug and alcohol abuse spanned decades of seemingly nonstop misery. There were years lost fretting over his relationship with Pattie Boyd, the ex-wife of his close friend, George Harrison of the Beatles. She had inspired the tortured song “Layla”, which remains a fantastic piece of music. Viewers of the film learn just how long his infatuation with Boyd lasted before it came to a maddening culmination and how Clapton remained unhappy despite finally winning her over.

The bulk of 12 Bars focuses on the period of Clapton’s emergence as a Blues guitarist through the “Layla” sessions. Many of his solo studio albums are dismissed as uneven and uninspired. After years of playing drunk onstage and making angry, embarrassing statements to his audience, he regained the great magic of his live concerts. There is a concert film produced in 2002, One More Car, One More Rider where he shines on acoustic guitar during “Bell Bottom Blues” with the late Billy Preston riffing beautifully on the organ. Clapton was also the band leader of a fantastic musical celebration of the life of the late George Harrison in 2002, “The Concert for George”, which recently was re-released in selected theaters.

12 Bars ends in the present with Clapton happily married and enjoying life with his children. He operates and funds an alcohol rehab center to assist those in need. He is set to perform concerts in October at Madison Square Garden. We can only hope that he has truly finally found peace of mind. And whether I am misinterpreting his guitar tone or not, I’ll always have the music of Cream and many other songs by Clapton to simply enjoy and assist me in my own personal journey in this life of the heart and mind.