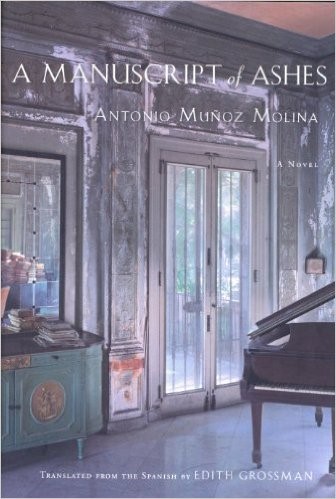

Book Review: A Manuscript of Ashes, by Antonio Muñoz Molina

By Bernie Langs

When the book A Manuscript of Ashes by Antonio Muñoz Molina arrived in the mail in a glorious hardcover edition, I knew that this unexpected present from my brother would become a special read. After all, my brother has the best literary taste of anyone I’ve ever met. After reading few pages, I paused realizing that the book was approachable but difficult in its sentence structures and in its form of shifting memories shared by narrators with unique perspectives of the events in the small Spanish town of Mágina over three decades.

Ashes is mysterious on many levels and it plays with readers’ sensibilities that everything read may not be truth, as the shifting perspectives may be unreliable. But each contains a kernel of truth as well. In Muñoz Molina’s book, the story centers around a period of Civil War and later, Franco’s fascist control where several key players are dragged off and face death or prison time so brutal that they emerge scarred for life, never letting go of the fear imbedded in their bones.

Ashes is mysterious on many levels and it plays with readers’ sensibilities that everything read may not be truth, as the shifting perspectives may be unreliable. But each contains a kernel of truth as well. In Muñoz Molina’s book, the story centers around a period of Civil War and later, Franco’s fascist control where several key players are dragged off and face death or prison time so brutal that they emerge scarred for life, never letting go of the fear imbedded in their bones.

In the late 1960s, the book’s protagonist, Minaya, escapes Madrid for Mágina in fear, and arrives at the home of his Uncle Manuel. He searches out the work and life of poet Jacinto Solana, who had lived there and violently died after prison. Solana had loved the same woman as Manuel, Mariana, who had upended Manuel’s family and friends with her beauty and dynamic manner. Mariana stands tall and powerful in this novel, though she is viewed obliquely and has little dialogue in the passages describing her time among this entourage. Tragically shot in the Mágina home (in the outdoor pigeon coop) on her wedding night with Manuel, it is discovered that it wasn’t a soldier’s bullet that felled her, but that she was murdered and possibly by someone within Manuel’s household.

The women in Ashes, be it Mariana, or the house servant Ines, who becomes romantically involved with Minaya, or Beatriz, who seeks out Solana after his release from prison in the 1940s and is in grave danger herself, or the harsh, reclusive mother of Manuel, Doña Elvira, ruling the household from her room in aged bitterness, are strong-willed, mysterious, and greatly shape the realities and lives of the men in the book.

As I read of the passionate love that Solana has for the elusive, alluring Mariana and felt his heartache as he awaited the wedding of Mariana to his school friend Manuel, I thought of something my own college friend told me: love was invented by poets and novelists, it wasn’t a naturally occurring phenomenon. While reading the love story in Ashes encapsulated in a murder mystery, surrounded by political intrigue and betrayal, I felt that Muñoz Molina could not have invented the intricacies of love for Mariana and the familial love (such as that between Solana and his tragic father), but that he’d drawn from experiences. We all feel and fall in love, and artists extrapolate on this and send it back out to us refined and beautiful. Then each of us have an even more intricate base for our next romantic experience. It is comparable to a Krebs Cycle going around and around, each piece a necessary cog of understanding to give us a pulse and a heartbeat, with an accompanied pang of discomfort.

Muñoz Molina’s sentence structures are constructions of wonder. I began to think of Homer’s Iliad at one point of the book, and the blind bard’s use of simile. For example, Homer wrote, “The hero would watch, whenever in the throng he had struck some man with an arrow, and as the man dropped and died where he was stricken, the archer would run back again, like a child to the arms of his mother, to Aias, who would hide him in the glittering shield’s protection.” Homer is the news reporter of the Trojan War, showing how all the armies involved were but chess pieces in a higher battle of the gods. But Muñoz Molina, as the author, is his book’s Homer, as well as its Zeus and Achilles. He takes on the role of all of his characters – and he hints gently at this throughout. Muñoz Molina’s similes turn back on themselves, to come around again to his plot and to his characters: “Doña Elvira’s laugh, he later told Ines, was a short, cold outburst that shattered like glass and gleamed for an instant in eyes unfamiliar with indulgence and tenderness, eyes open and inflexible and rigorously sharpened by the lucidity of her contempt and the proximity of her death…”

Perhaps Muñoz Molina could be considered a post-modern novelist, in light of his varying narrative tones, time periods, and shifting ambiguities. I was reminded recently in The New York Review of Books, that the philosopher Theodor Adorno wrote in his Mahler: A Musical Physiognomy on the early 20th century composer Gustav Mahler that he was music’s answer to the realist novel: “Pedestrian the musical material, sublime the execution.” Like Picasso did in painting, Molina stretches the constraints of his art form literature, to the breaking point and with astounding results.