Bernie Langs

Pulitzer Prize-Winning Journalist Stephen Kurkjian discusses the Gardner Museum Theft and the Podcast “Last Seen”

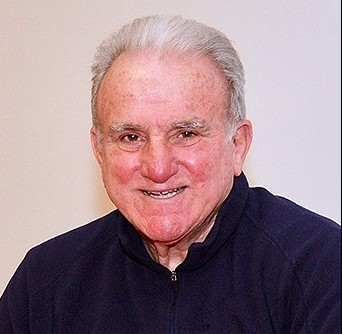

Stephen Kurkjian (photo courtesy of Mr. Kurkjian)

Courtyard of the Gardner Museum in Boston (photo: Bernie Langs)

“The Storm on the Sea of Galilee” by Rembrandt, stolen in 1990 from the Gardner Museum (photo: Wikipedia)

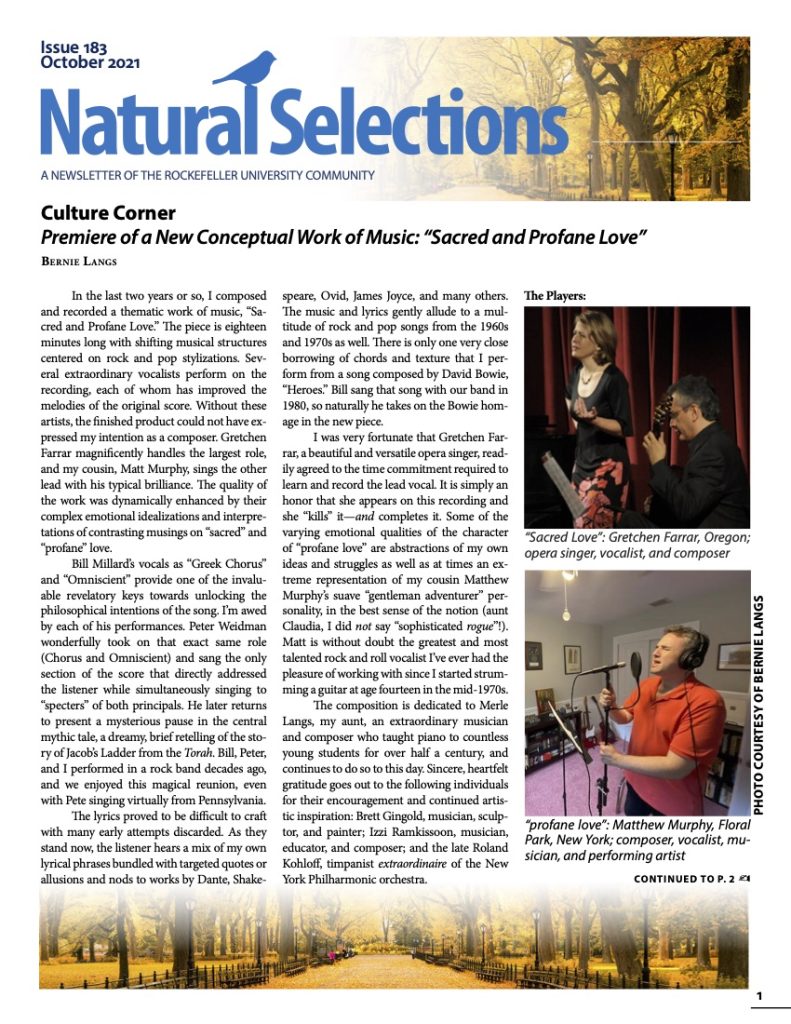

At 1:24 a.m. on March 18, 1990, two thieves disguised as policemen gained access to Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and made off with thirteen pieces of art, now valued at $500 million. The stolen works included Rembrandt’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee and A Lady and Gentlemen in Black, Vermeer’s The Concert, and Manet’s Chez Tortoni. Not one piece grabbed that night has been located despite the offer of millions in reward money for any credible information leading to the recovery of the paintings.

In 2018, The Boston Globe and Boston’s public radio station, WBUR, teamed up to create an investigative crime podcast about the theft. “Last Seen” is a fascinating dive into how the heist was pulled off and follows up on many potential leads about where these masterpieces may now be stashed and who may have been behind the heist. “Last Seen” boasts riveting audio of interviews and discussions with many of the key players surrounding the crime. The podcast audience also listens in on conversations with mob figures made by agents wearing wires, including those made by the FBI’s longtime art-crimes investigator, Bob Wittman. The search veers off in a multitude of directions as ideas are revealed and tested, mixing intense drama with unexpected moments of emotion and humor.

I reached out to The Boston Globe for comments about “Last Seen” and they directed me to Stephen Kurkjian, a retired Globe reporter and one of the show’s co-producers and lead investigators. A three-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Mr. Kurkjian is the author of the book, Master Thieves: The Boston Gangsters Who Pulled Off the World’s Greatest Art Heist, which continues his investigation into the Gardner theft. After a quick chat on the phone, I emailed Mr. Kurkjian questions about “Last Seen” and his involvement in the case.

Bernie Langs: The final episode of “Last Seen” is a panel discussion with you and others who worked on the production and reporting. You discussed your personal history as a Boston native, the son of an Armenian immigrant who became a commercial artist and taught you about the value of Boston’s cultural treasures. You explain, “…this is the artwork of the ages. Everything passes. Art endures. And this is our art. Mrs. Gardner put those on the wall for us, put them on the wall for my father.” Can you elaborate further about your obsession with recovering the art?

Stephen Kurkjian: I don’t see myself as “obsessed” by the Gardner story as much as I do doing what any investigative reporter would do—following a compelling story that has great meaning and purpose to their city. As an investigative reporter, especially one who grew up in Boston, I am drawn to stories that have “purpose” for the community. Mrs. Gardner had assembled this extraordinary collection for a transcendent reason—to motivate all Americans to be inspired by artistic achievement. She understood, having traveled the world over, that the civilizations that survived in time were not those that had the strongest military or economic might but those that valued art, be it paintings, statuary, tapestry, music, etc. While America was becoming a world power during the Industrial Revolution, she did not see us gaining an appreciation for art and she wanted to do something about it. That is why when she opened the museum she insisted that attendance be free of charge—except for a donation, if possible—and she encouraged local schools to send class after class to the museum so youngsters could be inspired by her art. On the personal side, my father, Anooshavan Kurkjian, a refugee from the Armenian Genocide, was one of countless art students who visited the museum daily so he could study the techniques of the artists. And though he was proud of the results of my investigative reporting in other areas, he was especially pleased when I turned my sights to the Gardner case. “You have to stir the conscience of the community for it to understand the fullness of what was lost here,” he stressed.

BL: The podcast covers how you and others follow-up each credible lead. The Boston FBI refused to speak on the record in reply to your queries. One can’t help but speculate about why they repeatedly dropped the ball in this case, effectively ruining some of the undercover efforts and remaining secretive when they should have mobilized the city’s residents to assist in identifying suspects. Is it possible that the FBI killed leads about the theft for nefarious or duplicitous reasons?

SK: Following this story is difficult enough and I’ve sought to avoid chasing conspiracy theories. That being said, it is also true that the FBI has not covered itself with glory in pursuing the case. Yes, the agents assigned to the case have done so with diligence, but my complaint is that the agency has failed to act creatively in its investigation. They have restricted other agencies, especially the Massachusetts State Police and Boston Police, from playing a leadership role on the case. That was regrettable, especially at the start of the investigation, as these other agencies would have had valuable sources and resources to put to the effort. Why? Likely because the agency didn’t want to jeopardize its confidential intelligence to these other agencies in fear leaks might happen. Also, I think at the outset the FBI believed that the case would be solved quickly—either through an arrest or an exchange that gained the arts’ recovery. And the FBI and U.S. attorney’s office didn’t want to share the glory that would come from such a recovery with any lesser agencies.

While it may not point to a conspiracy, I remain intrigued as to how the FBI could have muffed the investigation at several key points. Why not focus on [museum guard] Abath more widely and intensively at the probe’s outset? More recently, why release a tape in August 2015 that seemed intent on finding the identity of a stranger who was allowed into the museum the night before the theft, and disregard the outreach of several former staffers who willingly told me that it was not a suspicious entry at all and identified him as the former security deputy director? How did the FBI misplace key forensic evidence taken from the scene of the crime that was not available decades later when officials wanted to do advanced DNA testing on the material? But my sense is that taken together these amount not to a conspiracy to impair the investigation rather than a lack of expert and strategic thinking about how to advance it.

BL: “Last Seen” grabs the audience from the very first episodes. When you tracked down the guard, Rick Abath, living in a shack in Vermont, was that an important find for you, when you discussed the suspicion that he may have been the “inside man” in the theft?

SK: I did that interview with Abath, and taped it, for a profile I was doing on him for The Boston Globe, not the podcast. He was willing to speak—for the first time, on the record—as he was thinking then of coming forward with a book on his involvement with the case. But I had interviewed him many times in the years before that, since 2005 in fact, when I originally found him living in Vermont. I had spent the entire day trying to find his whereabouts in that city, and when I finally found his house, a tiny cabin on a remote hillside, only the moonlight led me to his front door. Interestingly, he wouldn’t let me in but agreed to an interview in a city tavern. That was an exciting interview, as for the first time I was learning details of the theft that the FBI and the museum had never made public.

Included in it was how Abath acknowledged his two grievous errors in letting the thieves into the museum. He thought some kids drunk from the St. Patrick’s Day celebration had jumped the iron fence behind the museum and were possibly causing damage to the Gardner’s rear premises…he fell for the thieves’ ruse…he feared he’d be arrested and miss the Grateful Dead concert that he had a ticket for in Hartford later that night. But he was convincing in his assertions of innocence, that he was not part of any robbery scheme, nor could he recall ever giving security secrets to any gangster-types who could have used them to pull off the heist. I have detailed other reasons that raise suspicions about Abath’s actions that night in my book, Master Thieves, but the FBI has never had enough to arrest him for involvement in the crime.

BL: My own theory about the theft had always been that it was financed by an eccentric collector utilizing mobsters to grab the art for his private collection. “Last Seen” destroys the wealthy villain mastermind idea making it clear that this was a well-planned theft by seasoned criminals. Can you explain why you know that this is the scenario that makes the most sense?

SK: No one “knows” anything about this robbery. No one knows for sure who did it, how they conspired to do it, or what happened to any of the art work. My thinking is all informed by hard reporting and deductive reasoning built off that reporting. If the theft had been engineered by a “Dr. No”-type criminal, an oligarch-type or arch criminal, who commissioned the robbery in hopes of gaining a beloved masterpiece, then I doubt that the thieves would have been so rough in how they treated the works they stole. Remember, all paintings were broken out of their frames, and the two large Rembrandts were cut out of their backings. I’m thinking the mastermind who may have commissioned the theft would have been very upset by such treatment. Also, with thirteen pieces being stolen, you would think that if they had been divided up, that someone would step forward or screw up so that the authorities would get a trail to a recovery.

But the feds told me in 2010 that the FBI had not had a single “proof of life sighting” of any of the thirteen pieces, which in FBI lingo means that there had not been a photo taken of the pieces showing their whereabouts since the theft or a single piece of forensic evidence, which would show that a person could back up their claim that they had access to or knowledge of the whereabouts of the stolen pieces. Which leads me to the belief that the pieces were stolen as a potential “get out of jail free” card for someone already in jail or someone who was facing a prison term. In the last chapter of Master Thieves, I tell the tale of just such a person, a mob leader who had been jailed four months before the Gardner heist, and the person who pledged to help get him out of jail.

BL: You have won Pulitzer Prizes, worked on investigations with The Globe and their famous Spotlight team. You have written about everything from the clergy abuse scandal inside the Boston Archdiocese to political scandals in Washington. Master Thieves continues your investigation into the Gardner heist. You retired in 2007, yet here you are still trying to recover those paintings.

SK: I was a founding member of The Boston Globe’s investigative Spotlight Team. It was commissioned in the early 1970s to work on stories that had purpose to Boston and New England, and its three Pulitzer Prizes, 1972, 1980, and 2003, are evidence to the success of focusing on such stories. I regard the Gardner as a similar story and backed up by my personal ties to the museum via my father and my cousins, both of whom were classical pianists who often performed at the museum. Because of those ties, I have come up with an alternative approach to gaining a recovery—a full-fledged public appeal, which would be powered by social media. I remember what attention the “Ice Bucket Challenge” gained in the summer of 2014 to ALS research. I think a similar drive should be established to bring the public attention and energies towards a recovery. Such an appeal would include outreach to all segments of society both those law-abiding and criminal. The message should be that these masterpieces were put on the museum’s walls for all Bostonians, rich and poor, and that they remain missing (hidden somewhere!) serves no purpose. My sense is that no one knows where the artwork was hidden, and the two thieves and their boss who did know the whereabouts are now dead, as the FBI confirms. But there are still people alive who know or have suspicions about who did it, and what they may have done with the artwork. But those people are unlikely to say something because to do say is breaking some mob code of “omerta,” and to bring forward such information would be considered “ratting.” The conscience of these people has to be engaged and they have to be reminded that many of history’s greatest artists, including Van Gogh and Michelangelo, came from impoverished backgrounds like they and their families. Perhaps their grandchildren could be inspired by one of those masterpieces to become an artist but they need to be back on the museum gallery’s walls. They are doing no good being hidden away. It is time that they be returned. Regrettably, neither the FBI nor the museum has seen fit to advocate for the social media campaign.

Please visit Mr. Kurkjian’s Web site for additional background on his fantastic career: http://stephenkurkjian.com/. To reach Mr. Kurkjian regarding his work on the Gardner theft, email stephenkurkjian@gmail.com.