Book Review: Compass by Mathias Énard (New Directions, 2015; translated into English, 2017)

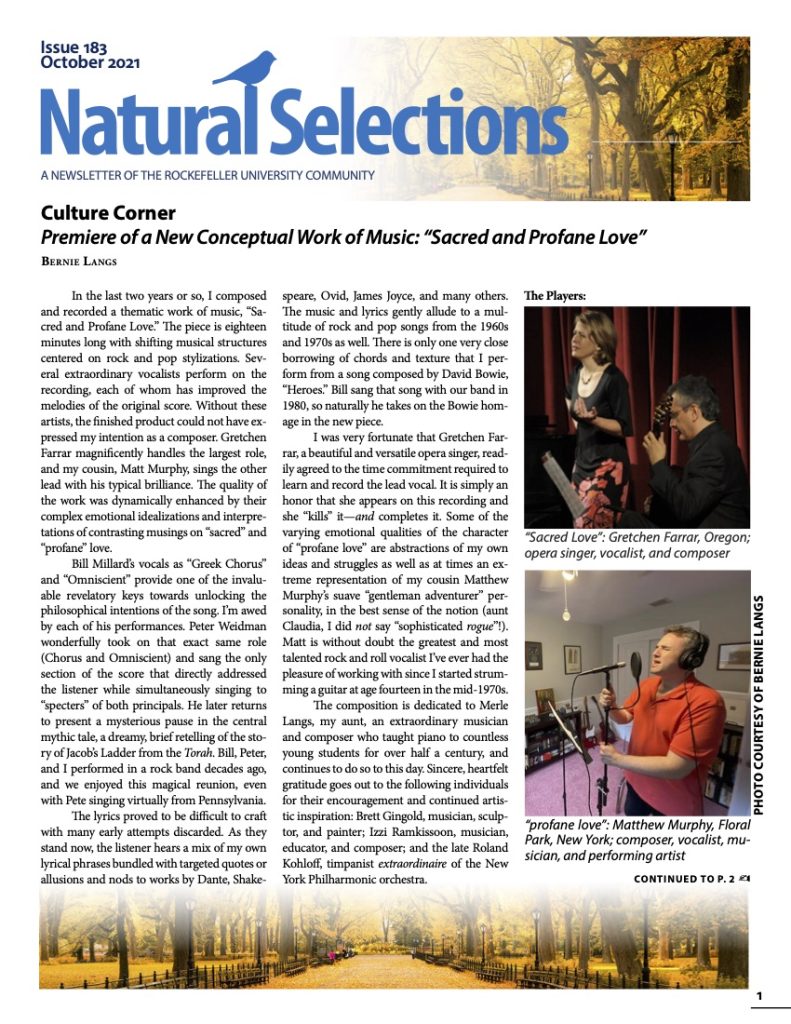

Bernie Langs

There are novels that are categorized as literature and not merely as fiction, and then there are the geniuses of literature and the masterworks of the genre. Reading these masterpieces of literary creation, we enter a process of joyful sublimation to the voices and experiences of unique characters, and we become witnesses to the colorful imaginations of the authors. One surrenders to the writers’ individualized and distinctive tones of language and states of mind as they conjure up realities that arise from a void as an expression of the acrobatic mental instincts which the best authors can relay through the art of written prose. A master of literature can construct a great sentence, a stunning paragraph, an unforeseen set of plot circumstances, and create an entire sublime world for their tales and stories.

I have recently read an amazing book, a true masterpiece, by the French author, Mathias Énard (b. 1972). Compass was published in 2015 and translated into English this year. It is simply the most wonderfully powerful work of fiction I’ve read in recent memory. It was a winner of the 2015 Prix Goncourt (a highly regarded prize in French literature). Compass clocks in at a lengthy 443 pages and is a difficult read. It is dense with nonstop ideas and an incredible number of facts on many topics, none of which are dropped easily into the text by the author. Énard’s book reflects his voluminous, deep knowledge of the many subjects he addresses, often expressed as anecdotes from the arts, literature, nonfiction tomes on many subjects, from obscure moments in history and most importantly, from the flavors and ideas of distant and mysterious lands.

I have recently read an amazing book, a true masterpiece, by the French author, Mathias Énard (b. 1972). Compass was published in 2015 and translated into English this year. It is simply the most wonderfully powerful work of fiction I’ve read in recent memory. It was a winner of the 2015 Prix Goncourt (a highly regarded prize in French literature). Compass clocks in at a lengthy 443 pages and is a difficult read. It is dense with nonstop ideas and an incredible number of facts on many topics, none of which are dropped easily into the text by the author. Énard’s book reflects his voluminous, deep knowledge of the many subjects he addresses, often expressed as anecdotes from the arts, literature, nonfiction tomes on many subjects, from obscure moments in history and most importantly, from the flavors and ideas of distant and mysterious lands.

The story in Compass is narrated by a brilliant musicologist who ruminates through the complexities of his lifetime that borders on, but never gives completely into, a total disaster. The protagonist, Franz Ritter, is in the throes of horrific insomnia at home in an apartment in Vienna as he delves deep into the memories of his travels through the Middle East and his scholarly pursuit to expose and relate the interconnections throughout history between Eastern and Western (mostly) classical music. One might think this a dry subject, but the emotional passion of Franz and those who shared his quest of making the twain of East and West meet makes for a gripping story. Franz’s baseline tale always returns to his love over decades of the brilliant French academic, Sarah. The reader comes to realize that Franz is now most likely deathly ill, and as we hear the sad details of his strange, mostly unrequited love for her, Énard immerses us in Franz’s consuming melancholy, all the while understanding his odd, unexpected strength. Through thick and thin, he is able to remain above water and not drown in a flood of bitter regret.

Franz is as complete a character as one could ever meet in fiction; always consistent, always real in so many detailed ways in his actions, words and thinking. His many admitted shortcomings still never lead the reader to dislike him. In the stories of the scholars and adventurers that he has met in his life while visiting places such as Istanbul, Tehran, Damascus, and Aleppo, there are numerous acts of duplicity and cruelty, and in Franz’s own case, pettiness. And it is the same with the tales he tells at length about the actions of the eccentrics of the past. Yet within this odd brew, there are grand redeeming moments of love and heroism, from both Franz’s lifetime and from the examples of men and women unearthed from the historical records, those from the desert sands of time.

Sarah rises above these flaws of personality, suffering only from the more intellectual quirk of the occasional fascination with the macabre. As Franz describes his own research of the history of music and delves into Sarah’s complex studies, the reader learns details of their work, with dozens of references to Middle Eastern composers and writers, as well as histories of individuals from the past with like-minded obsessiveness. They were Westerners who went against the grain and saw the allure of these mysterious, disconnected lands.

Here is one random, wonderful passage: “The human heart is indeed a strange thing. Franz Liszt’s artichoke heart didn’t stop falling in love, even with God—in these reminiscences of opium, as I hear the virtuosities of Liszt that occupied me in Constantinople rumbling like death march drums, a singular girl also appears to me, over there in Sarawak, even if Sarah has nothing in common with la Duplessis or with Harriet Smithson (“Do you see that fat Englishwoman sitting in the proscenium,” Heinrich Heine has Berlioz saying in his account), the actress who inspired the Symphonie Fantastique. Poor Berlioz, lost in his passion for the interpreter of “poor Ophelia”: “Poor great geniuses, grappling with three-quarters of the impossible!” as Liszt writes in one of his letters. You’d need a Sarah to be interested in all of these tragic fates of forgotten women…”

Although he is brilliant, Franz is fully aware and accepting of his scholarly limitations, and, wandering his apartment in sleeplessness, he admits he never reached the top as an academic. Both Franz and Sarah are studies in complete devotion to the work itself and to the process of slow and steady, exciting, absorbing discovery. Compass is a brilliant tale of intellectual pursuit that is always in tandem with the underpinning emotion of love as a concurrent force. It is a love which goes naturally with a researcher’s ideas, and as a given that is always present during the events of their lives and in history itself.

The other melancholy, terrible theme of the book is how Franz sees his beloved Middle East devolve to its current situation of war, fundamentalist religion, and miserable violence. We read the awful tales of friends caught in Iran during the Revolution and the destruction of the people and places he’s long loved, and been in awe of, by the barbaric, ruthless armies of ISIS or as victims of Assad in the Syrian civil war. It’s a heartbreaking story of what has been lost, tinged with the sadness of what could have been.

Franz is not a showy intellectual. He never brags about his incredible knowledge and though his studies take him to the heart of the Middle East, to the dangerous cities and outskirts of Iran, Turkey, and Syria where he is clearly a Western outsider, his tunnel vision of discovering artistic and scholarly connections between East and West exposes his disconnect, which leads to a defeat. This all collapses into the mire of today’s horrific problems. Franz and his colleagues didn’t blind themselves to the coming storm by studying in America or Europe encased in an Ivory Tower at a university, mulling over The Arabian Nights, simply reading, lecturing, and attending conferences. But while they put their boots on the ground and ventured abroad, they roamed within the intellectual, fortified towers of their minds and did not stop to consider that there might be something possibly irreversibly horrific being conjured up before their very eyes, even though the region’s history gives them all the glaring warning signs.

As I read Compass, I was completely captivated by the intense musings of the inner states of Franz Ritter’s unique and fascinating mind. Mathias Énard writes beautifully, like a once in a decade master of literature, and I look forward to more novels by this brilliant man.